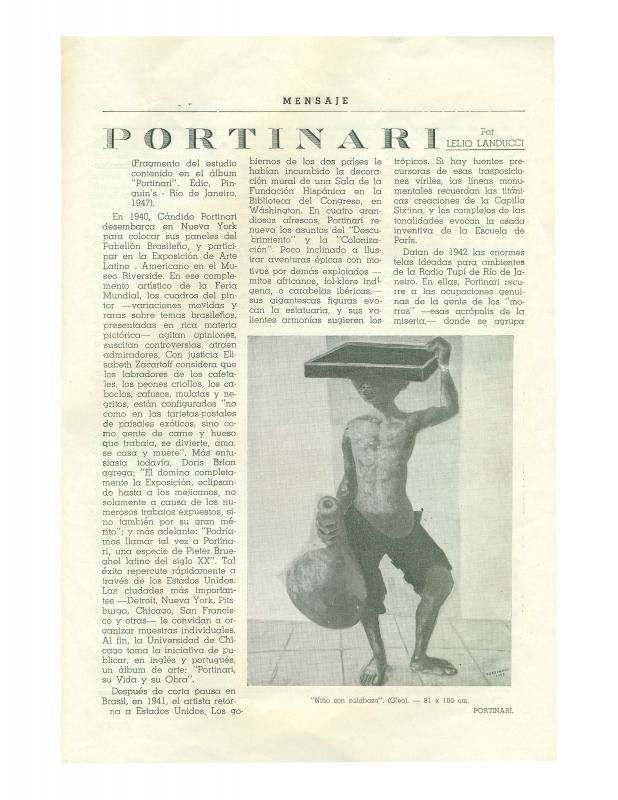

The conference talk that the artist Candido Portinari (1903–62) delivered on September 12, 1947, at the Verdi Theater in Montevideo under the title “Sentido Social del Arte” revisits what is known in art as the dichotomy between form and content. He lived in Uruguay during the time where from the perspective of the TTG (Taller Torres García) and from the Rio de la Plata’s inclination toward geometric abstraction, the idea of figuration was being rigorously and harshly questioned. Portinari’s discourse, however, had a “virtue” that successfully conveyed the eclectic romanticism that prevailed over time in the aesthetic and political thinking of the Montevidean cultural medium. Despite being treated with harsh antagonism by the TTG, Portinari received praise from politicians, prominent figures from different disciplines, artists, and recognized Catholic activists who were against the communist ideas preached by the Brazilian to the intellectuals of Montevideo. The peculiarity of Portinari’s discourse was his confidence in an educational matrix for social art, since an individual must not only be educated as an artist, but also educated in how to be “socially consenting” and sensitive to collective suffering. Even though he recognized that the “subject” was not specifically something to be expressed using the visual arts, Portinari defended that his consideration made the painting “readable” “for the sake of those who struggle…”

In 1947, Portinari visited Montevideo, staying for a long time in the city, fourteen years after the visit of another celebrated artist, David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974). Between 1933 and 1947 in Uruguay, he had developed art with social purpose that was closely linked to the formal principles of Mexican muralism. Due to Portinari’s long stay in the country, his exhibitions in September of 1947 and April of 1948, and the fact that in Montevideo his designs for the large mural A Primeira Missa no Brasil were beginning to take shape, made him a reference for “leftist art.” Nevertheless, his realism was imbued with mysticism, with a humanistic lyricism, and was influenced by the European post-Cubist trends of European art, which diametrically distanced him from the Mexican artist. In effect, what Portinari wanted was to demonstrate that the legacy of modern art was a compilation of inexhaustible expressive resources that could be placed in the service of a realistic theme, that were ethically and politically appropriate to the demands of the second postwar period. In a sense, in the Uruguayan capital, Portinari expands on the idea of a realistic “modern style” of art, a politicized art with nationalistic principles, with formal presuppositions about modernity.

[For further reading, please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following texts on Portinari’s presence in Uruguay: “Cándido Portinari no es un creador,” by Guido Castillo (doc. no. 1263707); “Latitud Sur 34º, Longitud 58º Oeste. Exposición Cándido Portinari,” by Alfonso Domínguez (doc. no. 1226448); “La libertad en Portinari” (doc. no. 1225346), and “La Primera Misa, mural de Cándido Portinari,” by Cipriano S. Vitureira (doc. no. 1312738); and “Portinari,” by Lelio Landucci (doc. no. 1312931)].