In 1946, the art critic Cipriano Santiago Vitureira (1907–77) had already presented a conference entitled “Sentido Humanista de la Pintura Brasileña Contemporánea” at the Ateneo de Montevideo. The conference was given to inaugurate a Brazilian exhibition of thirty-five lithographs where he also demonstrated interest in studying the artistic culture of the neighboring country. In this article, Vitureira highlights the “majesty and elegance” in the drawing, the “form’s classicism” and the “respect for history” in the work A Primeira Missa no Brasil by Candido Portinari (1903–62). Vitureira pointed out that although this work appeared with these nineteenth-century artistic attributes, they were at the service of “modern sense of visual art beauty.” In a particular sense, the author was drawing attention to the differences between the work of the Mexican David Alfaro Siqueiros, although his assertions seemed to suggest the contemporary art produced by the TTG (Taller Torres García), which cultivated “ahistorical” art, contrary to the “majestic and elegance” and for which “the classic” was not an attribute of the type of art, but rather a Constructivist trend in search of a great tradition, as Joaquín Torres García would say.

In 1947, Portinari visited Montevideo, staying for a long time in the city, and fourteen years after the visit of another celebrated artist, David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974). He had developed, between 1933 and 1947 in Uruguay, art that had a social purpose that was closely linked to the formal guidelines of Mexican muralism. Due to Portinari’s long stay in the country, his exhibitions in September of 1947 and April of 1948, and the fact that in Montevideo his designs for the large mural A Primeira Missa no Brasil were beginning to take form, made him a reference for “leftist art.” Nevertheless, his realism was imbued within mysticism, with a humanistic lyricism, and influenced by the European post-Cubist trends of European art, which diametrically distanced him from the Mexican artist. In effect, what Portinari wanted was to demonstrate that the legacy of modern art was a compilation of inexhaustible expressive resources that could be placed at the service of a realistic theme, and that were ethically and politically appropriate to the demands of the second postwar period. In a sense, in the Uruguayan capital, Portinari expands on the idea of a realistic “modern style” of art, a politicized art with nationalistic principles, with formal presuppositions about modernity. The exhibition by the Brazilian artist Portinari in Montevideo was well received, particularly by the intellectual sectors linked to the political left, but also by the more conservative Catholic sectors, since the Brazilian artist cultivated a Christian background in his human figures. He received strong criticism from the group led by Joaquín Torres García (1874–1949) for performing “imitative” art that was only concerned about transmitting emotional statements.

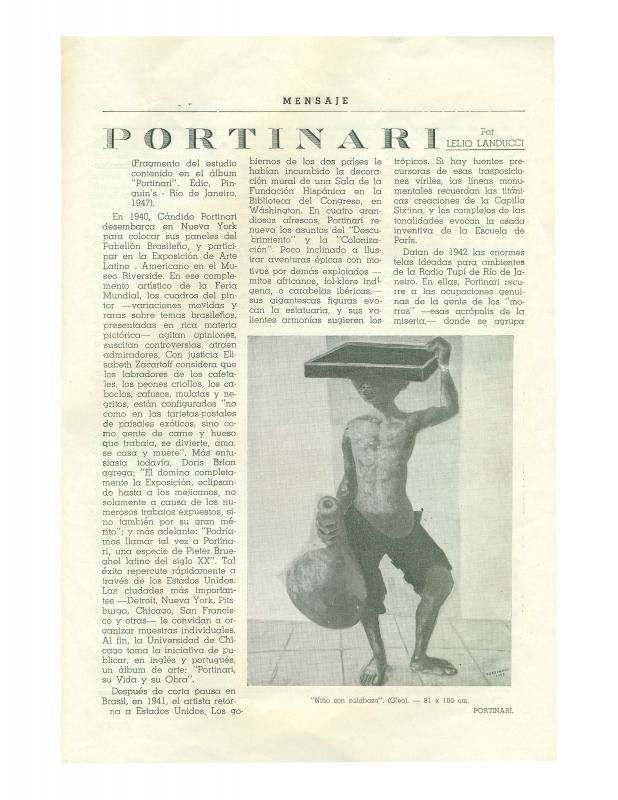

[For further reading, please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following texts on Portinari’s long stay in Uruguay: “Sentido social del arte,” by Portinari (doc. no. 1313089); “Cándido Portinari no es un creador,” by Guido Castillo (doc .no 1263707); “Latitud Sur 34º, Longitud 58º Oeste. Exposición Cándido Portinari,” by Alfonso Domínguez (doc. no. 1226448); “La libertad en Portinari,” by Cipriano S. Vitureira (doc. no. 1225346); and “Portinari,” by Lelio Landucci (doc. no. 1312931)].