In August 1947, when Cándido Portinari (1903–62) arrived in Montevideo, he gained the disciplined support of his comrades at the PCU (Uruguayan Communist Party) and the AIAPE, some of whom were artists working in a social realist style. The Brazilian artist encountered resistance from his political adversaries, and he was also met with hostility by the TTG (Taller Torres-García). In the first place, Portinari’s idea that muralism was an expanded version of easel painting was diametrically opposed to the teachings of Joaquín Torres-García (1874–1949), who believed that mural painting followed strict rules referring to the plane that had nothing to do with traditional easel painting. In the second place, Portinari’s works dealt with figurative and sentimental subjects, which Torres-García dismissed as “literary painting.” David Alfaro Siqueiros’ political message, which was based on an aesthetic that relied entirely on itself (with no drama or sentimentalism), was therefore far more acceptable to Torres-García than Portinari’s “humanist” message, whose emphasis on the suffering of the dispossessed seemed to be frankly narrative, and thus “false” in Torres-García’s assessment. As it says in the article in Removedor magazine: “Portinari arrived surrounded by pretty words and introduced by impressive names [the Frenchmen [Louis] Aragon, [Jean] Cassou, etc.]. But pretty words and pretty names pay tribute to the lie of their time, which is stronger than they are […].”

Several conflicting discourses were involved in this situation. One of them became particularly important when Portinari arrived in Uruguay: the idea of social realism as conveyed in the discourse of a modernity that had been renovated by the Marxist criticism expressed by the French model. Its paradigm was Pablo Picasso, a communist who had been a member of the PCF (French Communist Party) since the Liberation of Paris in August 1944. The quest for an international centrality for this aesthetic-political discourse led to an alliance with the nationalisms that were being consolidated in Latin America at the end of the war. Torres-García was far removed from this scenario and had nothing to do with it; he was looking for an “Abstract” and “Universal Man” of the ages. Meanwhile, the political and ideological debate stirred up in Uruguay by the worldwide crisis favored a form of humanism that was closely aligned with the historical circumstances of the time, a form of humanism that was nurtured by socialist utopianism and by the Marxist ideas that became firmly embedded in the French model before and after the Second World War.

Over and above all those considerations, however, this article by Guido Castillo (1922–2010) has an unhappy ending. It reveals that its underlying complaint is almost always rooted in the TTG’s competitive jealousy regarding any kind of mural painting that did not fall within the parameters of its own doctrine.

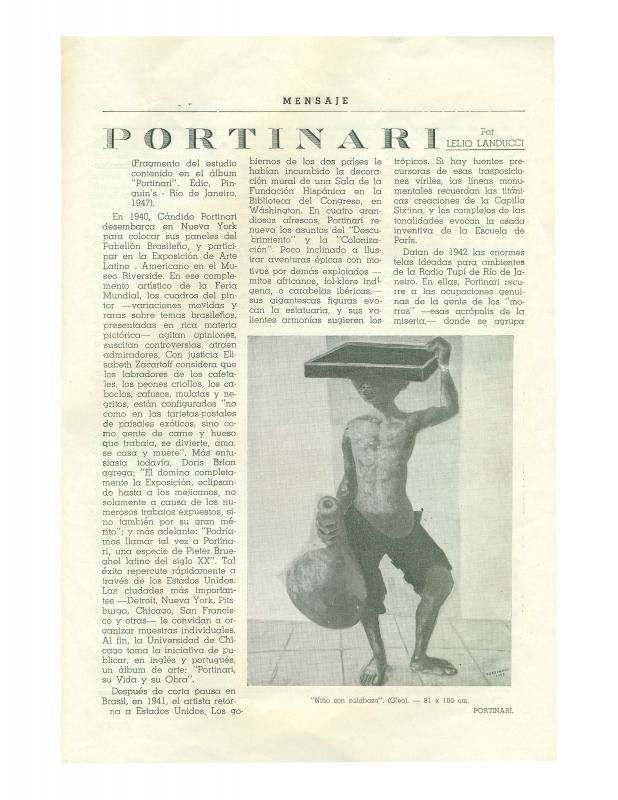

The Brazilian painter Cándido Portinari arrived in Uruguay in 1947, at a time when the country was enjoying a measure of economic development thanks to the industries created by the import substitution program that had been implemented because of the Second World War. There was a prosperous middle class that hungered for cultural activities. Portinari’s exhibition was therefore very well received, especially among left-leaning intellectuals, but also among more conservative Catholics, since the Brazilian artist created a Christian mood for the human figures in his works. Also, while in Montevideo, he produced the initial sketches for his large painting, A Primeira Missa no Brasil.

[As complementary reading, see the ICAA digital archive for the following articles about Portinari’s time in Uruguay: by Cándido Portinari “Sentido social del arte” (doc. no. 1313089); by Alfonso Domínguez “Latitud Sur 34º, Longitud 58º Oeste. Exposición Cándido Portinari” (doc. no. 1226448); by Cipriano S. Vitureira “La libertad en Portinari” (doc. no. 1225346), and “La Primera Misa, mural de Cándido Portinari” (doc. no. 1312738); and by Lelio Landucci “Portinari” (doc. no. 1312931)].