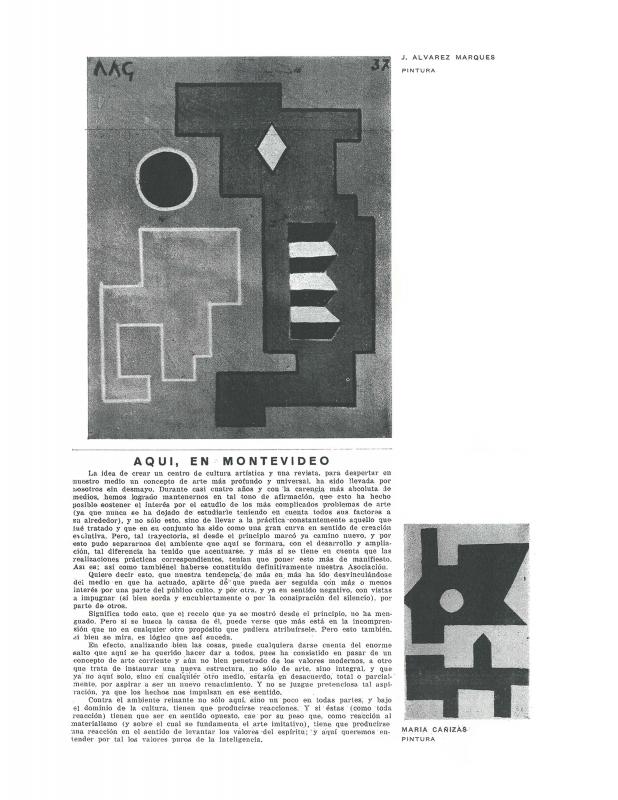

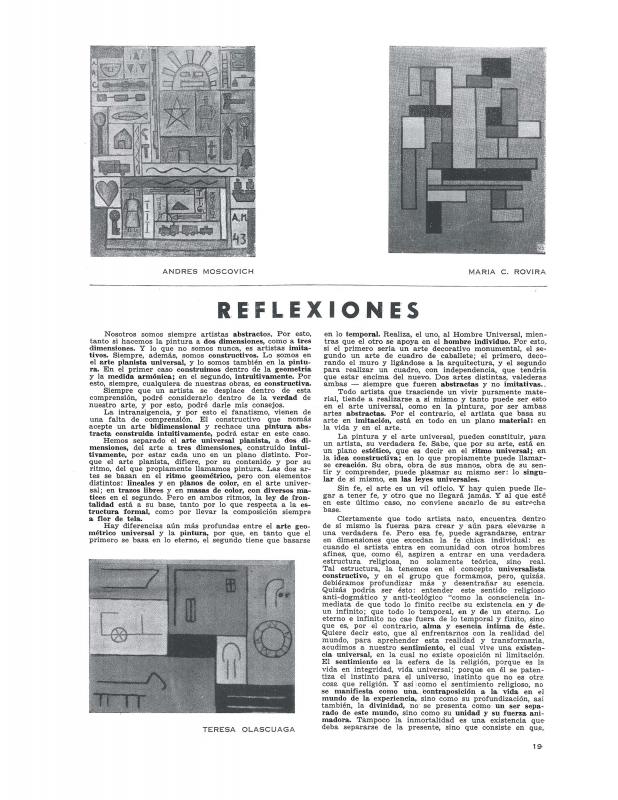

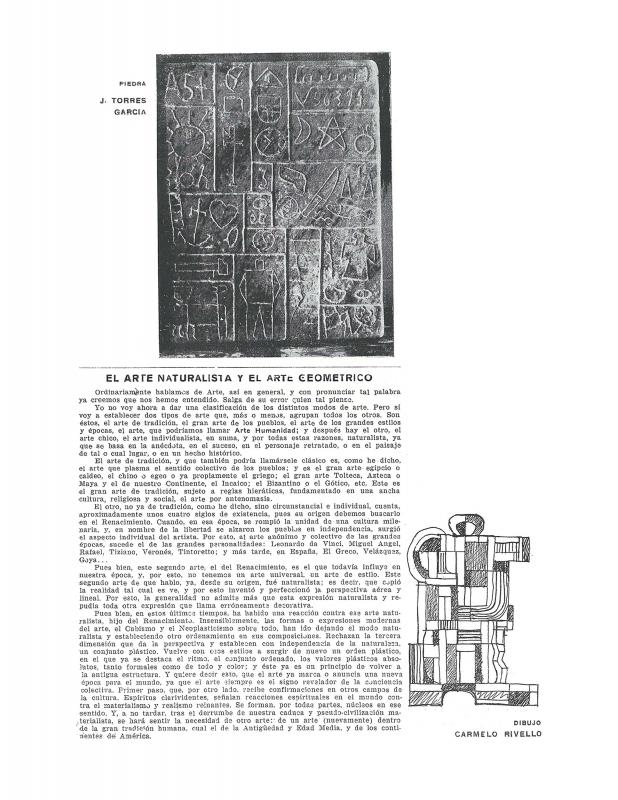

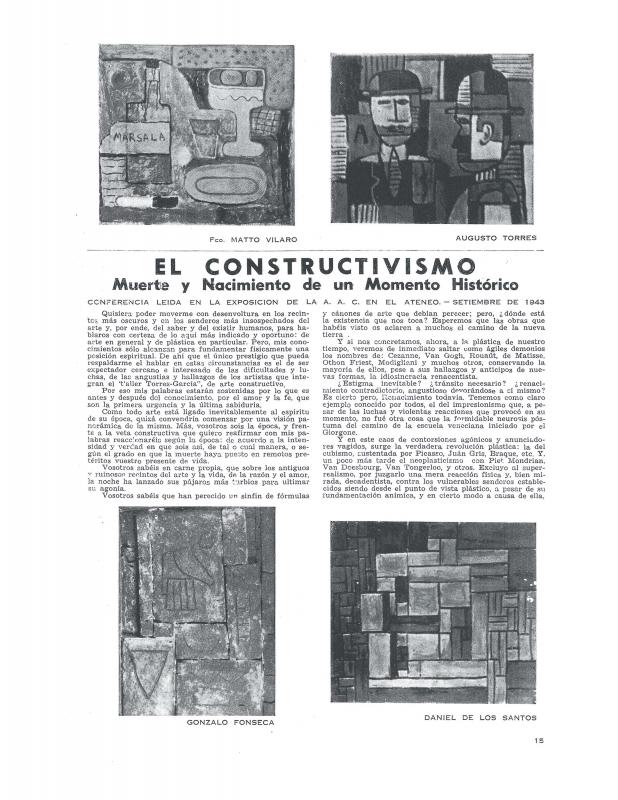

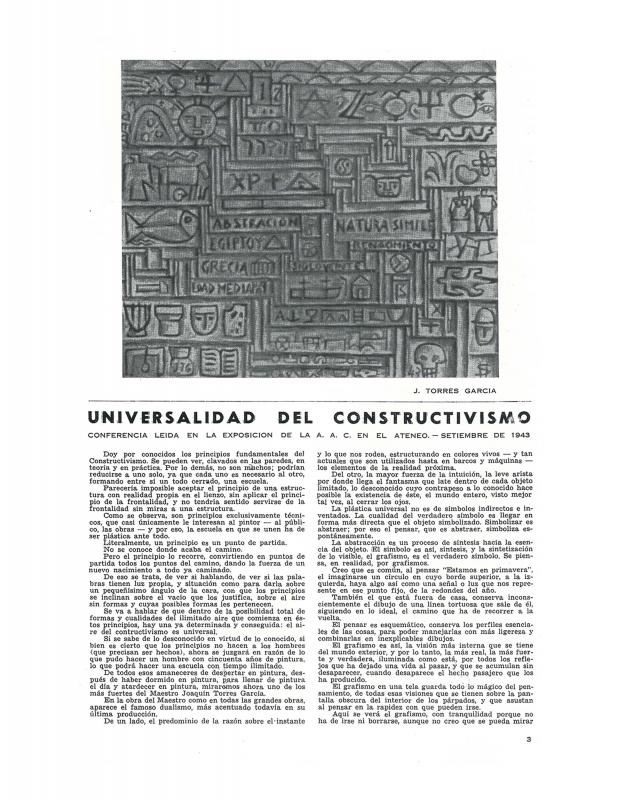

This article, which appeared in Círculo y Cuadrado (Montevideo, August 1936), was reprinted as “Lección 46” in the book Universalismo Constructivo, published by the Poseidón publishing house (Buenos Aires, 1944). The article was written for local readers, but it also had in mind the readers in Europe to whom Joaquín Torres García (1874–1949) regularly sent the publication. The Dutch artist Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), for example, who subscribed to Círculo y Cuadrado, at some point wrote about how pleased he was to see that Cercle et Carré (Paris, 1929) had been reborn in the new magazine. The goal was to introduce abstract art to a new audience, and the letter was published in Number 2 (August 1936) under the title “Le neo-plasticisme.” In the article reprinted here, JTG restates his main ideas about “abstract-concrete” art although, in this case, underscoring the question of modernity. The maestro insists that ‘the modern’ cannot be separated from ‘the archaic’ because both are part of the whole of a universal and abstract temporality. He emphasizes this point in order to distinguish it from how “modernity” was commonly understood, especially among Uruguayan artists at that time. To find ‘the classical’ in ‘the modern’ (through an appropriate form of art) is to place oneself on the eternal plane while dealing with contingent factors. This was why JTG saw the new forms of industry and mechanical technology purely as elements that could be used via constructive art to rise to the level of Universal Man or Abstract Man, over and above the problems related to the politics of human relationships and material relationships in the contemporary world. Attention should be drawn to the “correction” that appears at the foot of the page: having mentioned the Italian artist and theorist Carlo Belli (1903–91)—as well as the writer André Gide (1869–1951), the editor and activist Henri Barbusse (1873–1935), and others—JTG maintains that he could only agree with them in “the reality of the spirit,” while still disagreeing with them on the “material reality” plane. The Uruguayan maestro feels obliged to clarify that he is not prepared to accompany Belli in his foray into fascism, as expressed in his book Kn (Milan, 1935). JTG took particular pains over the Nazism issue, going so far as to give a lecture in support of Republican Spain in 1938 and reviling fascism as the farthest point from “individual-man” in terms of “Universal Man,” describing it as unbecoming to humans and the province of inferior beings. [As complementary reading see, in the ICAA digital archive, the following articles published in Cercle et Carré [Circle and Square]: by Joaquín Torres García “Aquí, en Montevideo” (doc. no. 1263116), “Reflexiones” (doc. no. 1263191), “La presente revista” (doc. no. 1262991), and “El arte naturalista y el arte geométrico” (doc. no. 1263101); by Guido Castillo “El constructivismo. Muerte y nacimiento de un momento histórico” (doc. no. 1263176); by Alexis Carrel “El hombre, una incógnita” (doc. no. 1263085); by Edgar Varèse “Nacionalismo y Folklore” (doc. no. 1263070); by Carmelo de Arzadun “Necesidad de agruparse para la formación de un medio artístico” (doc. no. 1263023); by San J. Luis Vicente “Nosotros y nuestro ambiente” (doc. no. 1263146); by Héctor Ragni “Nuestro arte constructivo y las teorías cubistas” (doc. no. 1263131), and “De qué pertenezco a la asociación de arte constructivo” (doc. no. 1263007); and by Francisco Lanza Muñoz “Universalidad del constructivismo” (doc. no. 1263161)].