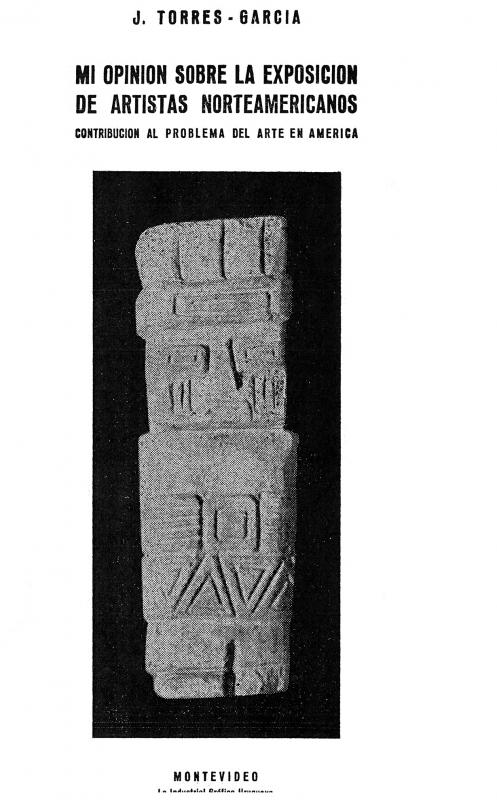

Shortly after returning to Montevideo in 1934, Joaquín Torres García (1874–1949) turned his attention to pre-Columbian art and began researching the ancient cultures of the Americas. He communicated his findings and conclusions in lectures and in articles such as “Metafísica de la Prehistoria Indoamericana” (1939), in which he stated that primitive pre-Hispanic art had achieved a perfect balance between abstraction, geometry, and signs with magical connotations. JTG did not seek to “imitate” that art but to identify with the cosmology of ancient Latin American cultures in order to create his ideograms in the Tradition of Universal Man that embodied the same “classical” sense he had identified in a dimension of antiquity that was not limited to Europe. In so doing, the maestro’s goal was to share “the transcendent,” to recognize in the indigenous people’s metaphysical faith the same mystical support that was the inspiration for constructive universalism. JTG thus rejected “the contingent” aspect of all folkloric interpretation of pre-Hispanic art and highlighted its universal background. In Hispanic America, ever since the nineteenth century, a parallel had existed between pictorial landscape art and political nationalism. Landscape painting sought to be an affirmation of the urban-rural collective identity or imaginary and of the political-territorial unity of national States. Edgar [Victor Achille Charles] Varèse (1883–1965) was a French composer who became a nationalized American. His music stressed tone and rhythm in an aesthetic that he described as “organized sound.” The tone was expressed as living matter or as unlimited musical space. He founded the Gremio Internacional de Compositores (1921) and, once he was in the United States, the Asociación Panamericana de Compositores (1926). He focused on experimental and electronic music and created projects he called “ionizations.” In the realm of popular music he had a huge influence on the North American guitarist Frank Zappa. It is no surprise that the Uruguayan version of Círculo y Cuadrado should have published a brief article by the composer Edgar Varèse, who returned to Paris (where he lived from 1928 to 1948), where he was rehearsing his work Étude pour Espace (1947), an important contribution to the early stages of concrete music. Varèse’s article begins by saying “I do not believe in nationalism in art,” a statement that was very much in line with the message preached by JTG, who was highly critical of this facet of local culture. The latter’s goal was to avoid the political opinions involved in “nationalist” feelings in order to produce art that incorporated aspects of regional reality and was resolved on a universal abstract plane. [As complementary reading, see the following articles by Joaquín Torres García in the ICAA digital archive: “Con respecto a una futura creación literaria” (doc. no. 730292); “Lección 132. El hombre americano y el arte de América” (doc. no. 832022); “Mi opinión sobre la exposición de artistas norteamericanos: contribución” (doc. no. 833512); “Nuestro problema de arte en América: lección VI del ciclo de conferencias dictado en la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de Montevideo” (doc. no. 731106); “Introducción [en] Universalismo Constructivo” (doc. no. 1242032); “Sentido de lo moderno [en Universalismo Constructivo]” (doc. no. 1242015); “Bases y fundamentos del arte constructivo” (doc. no. 1242058); and “Manifiesto 2, Constructivo 100%” (doc. no. 1250878)].