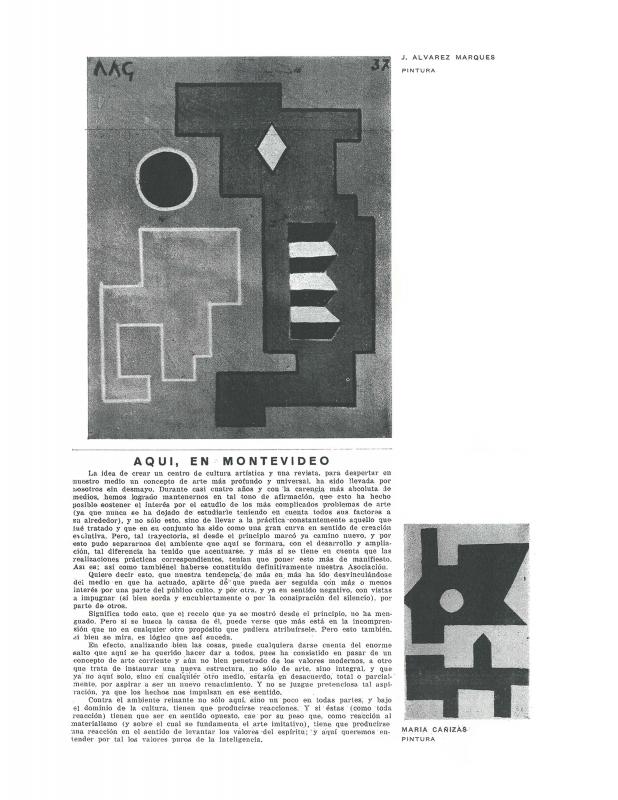

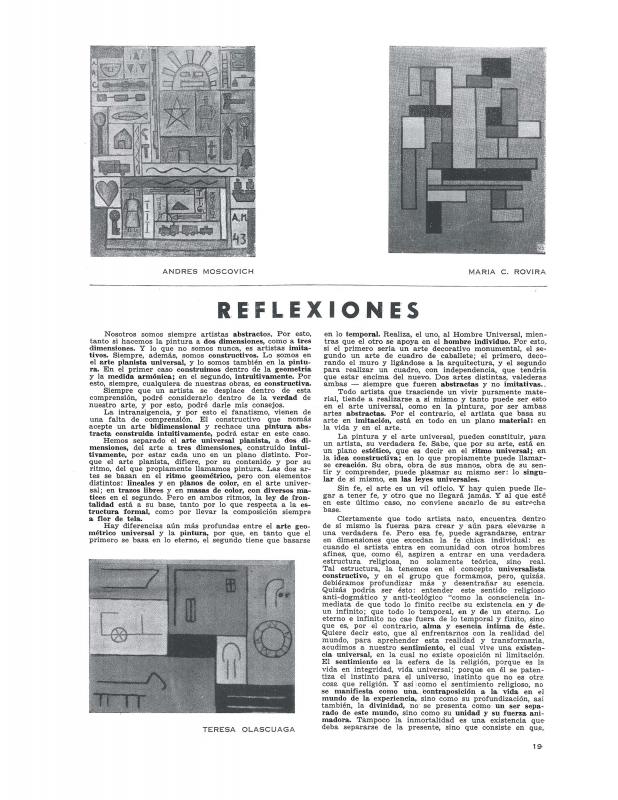

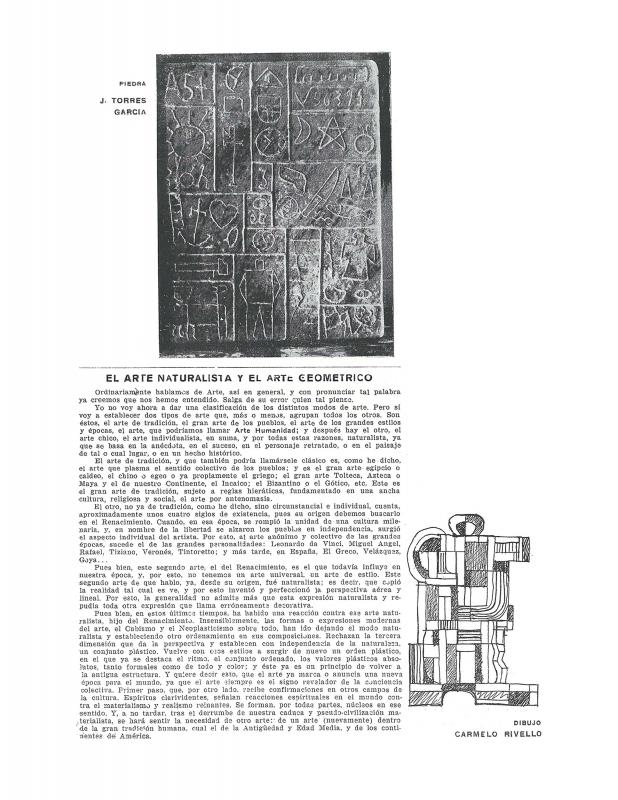

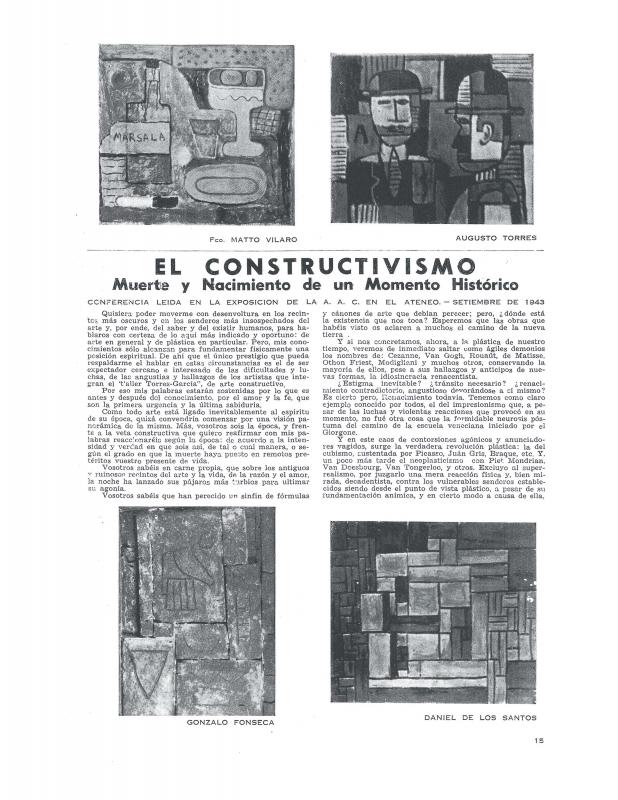

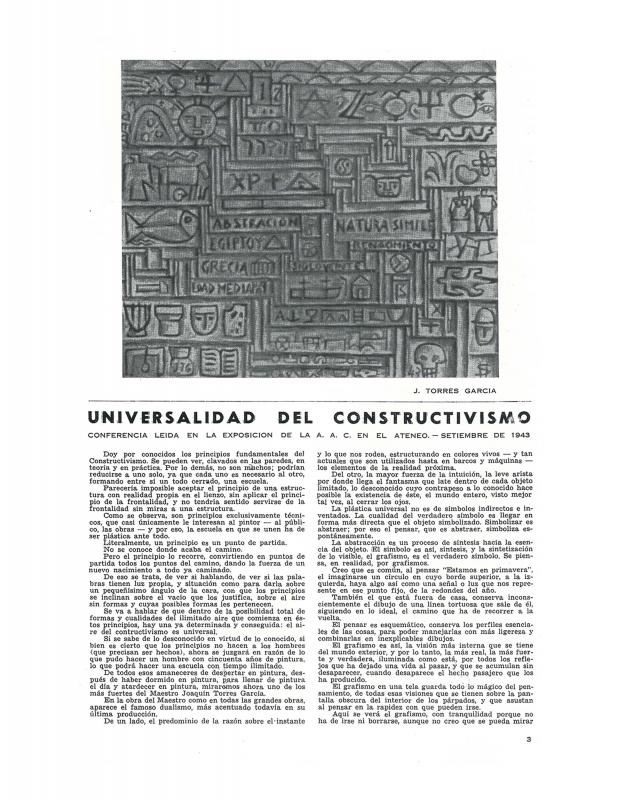

In 1934, back in Uruguay, Joaquín Torres-García (1874–1949) announced that he would create an environment that would be conducive to the “flowering of a superior culture.” The first artists to join him in that endeavor were Carmelo de Arzadun (1888–1968), the author of this text, Héctor Ragni (1897–1952), Amalia Nieto (1907–2003), Julián Álvarez Marqués (1898–1964), Gilberto Bellini (1908–35), José Cuneo (1887–1977), Luis Mazzey (1895–1983), Carlos Prevosti (1896–1955), Bernabé Michelena (1888–1963), and the Spanish artist Eduardo Díaz Yepes (1910–78), among many others. Torres-García set out to assemble a group of Uruguayan artists and create a link to and dialogue with the European avant-garde, as he had begun to discuss in the magazine Cercle et Carré (Paris, 1930), when the universality of abstract art was breaking down nationalist barriers. The magazine ceased publication in France in 1931, but its spirit lived on when the AAC (Asociación de Arte Constructivo) launched Círculo y Cuadrado in 1936. A long list of AAC members wrote for this journal, including Arzadun, Ragni, Nieto, Torres-García , and the Brazilian-born Rosa Acle (1916–90), among many Uruguayans. There were also several avant-garde European artists, such as Jean Gorin (1899–1981), Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), Ángel Ferrant (1890–1961), Jean Hélion (1904–87), Gino Severini (1883–1966), Theo Van Doesburg (1883–1931), or Chilean Vicente Huidobro (1893–1948), among others.

Arzadun’s article refers to the recently-created UAPU (Unión de Artistas Plásticos del Uruguay, 1935), whose goal was to nurture the State’s support for local art. While Arzadun was writing this article the UAPU was already in trouble; the Gabriel Terra (1933–38) dictatorship had already created the Comisión Nacional de Bellas Artes, a step that foreshadowed the dissolution of the Unión de Plásticos shortly thereafter. Arzadun makes no appeal to readers to join the AAC. Instead, taking his cue from Torres-García’s theoretical-practical teachings, he proposes “thoroughly discussing the role of the art problem.” In other words, Arzadun suggests that groups should not be based on circumstantial associations but should evolve out of a communion of aesthetic and ethical ideas.

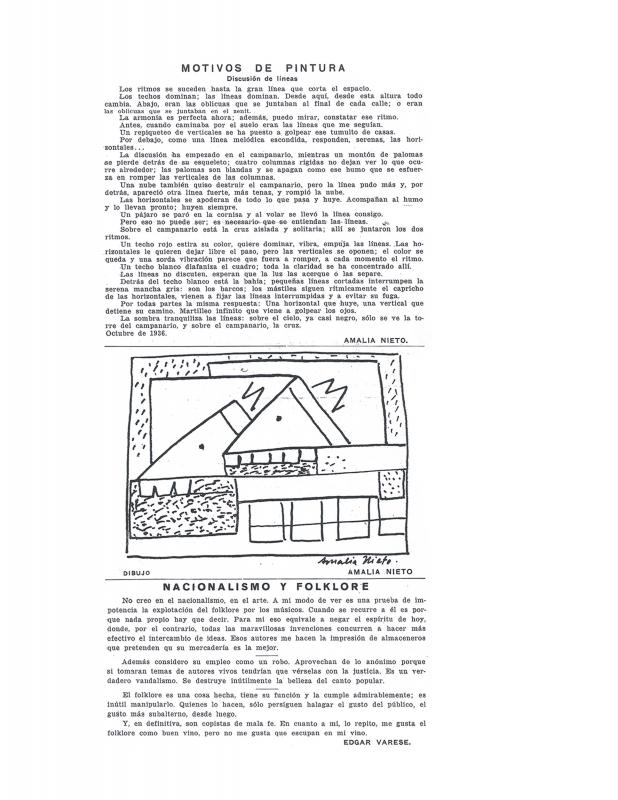

[As complementary reading, see the ICAA digital archive for the following articles published in Cercle et Carré (Círculo y Cuadrado): by Joaquín Torres-García “Aquí, en Montevideo” (doc. no. 1263116), “El plano en el que deseamos situarnos” (doc. no. 1263054), “Reflexiones” (doc. no. 1263191), “La presente revista” (doc. no. 1262991), and “El arte naturalista y el arte geométrico” (doc. no. 1263101); by Guido Castillo “El constructivismo. Muerte y nacimiento de un momento histórico” (doc. no. 1263176); by Alexis Carrel “El hombre, una incógnita” (doc. no. 1263085); by Edgar Varese “Nacionalismo y Folklore” (doc. no. 1263070); by San J. Luis Vicente “Nosotros y nuestro ambiente” (doc. no. 1263146); by Héctor Ragni “Nuestro arte constructivo y las teorías cubistas” (doc. no. 1263131), and “Por qué pertenezco a la asociación de arte constructivo” (doc. no. 1263007); and by Francisco Lanza Muñoz “Universalidad del constructivismo” (doc. no. 1263161)].