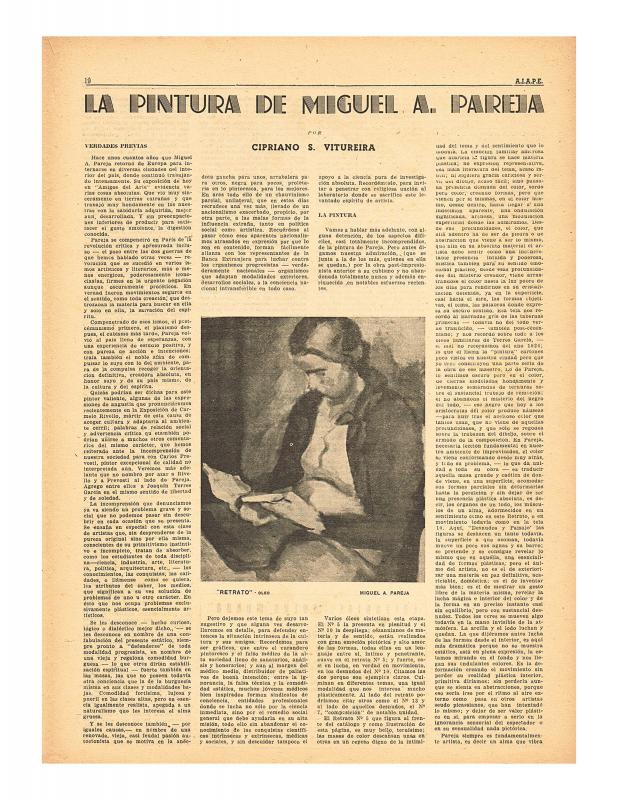

This article is on the eighth Salón Nacional de Bellas Artes (1944), signed “V” for Cipriano S. Vitureira (1907–1977)—who was a protagonist of the generational leadership that stimulated the formation of local guilds and associations of intellectuals, all of which were politically opposed to the de facto dictatorship of Gabriel Terra (1931–38) and additionally opposed to the advancement of fascism in Europe and Latin America in the thirties and forties. Among the associations formed was the AIAPE (Asociación de Intelectuales, Artistas, Periodistas y Escritores [Association of Intellectuals, Artists, Journalists, and Writers]). This article referencing the eighth Salón Nacional de Bellas Artes (1944) reflected the author’s preoccupation with artistic stimulus and diffusion. The key to this resolve resided with the election of judges to the selection panel that were independent of any political power, judges who fully endorsed the artistic medium. This was the only guarantee for the promotion of innovative visual art. [Please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following texts to this regard: (doc. no. 118660) and (doc. no. 1184568">1184568)]. Vitureira comments on the results obtained in the categories of painting and drawing, mentioning promising Uruguayan artists such as Carlos González (1905−1993), Amalia Nieto (1907−2003), Germán Cabrera (1905−1993), Washington Barcala (1920−1993), and the Chilean Felipe Seade (1912−1969) who had artistic prominence in the following decades and even internationally, in the case of Barcala and Cabrera. The author applauded the academic work that was ruled out by the judges, which he considered “right-wing reactionary forms” of production and artistic trinkets resulting from official stimuli in their thematic and artistic approaches. A series of ideological/artistic affiliations permeate the article, such as the criticism of the artists who sympathized with “Blanista” tendencies (an Edwardian academic artistic trend created by Juan Manuel Blanes) from the political right wing; the praise of “primitivism” was strong, local, and deeply rooted, such as in the work by [Carlos] González and the antifascism and anti-Falange by Joaquín Torres García (1874−1949). This last idea was not directly deduced from the works he presented but instead from the lectures he gave in support of the Second Republic of Spain (1931−39). This is the first national exhibition where the Uruguayan master presented European landscapes and for which he received an award. This award, given to the creator of constructive universalism, initiated various journalistic controversies that were instigated by the artist José Cúneo, and Carlos Herrera MacLean, one of the members of the selection panel. [For further reading, please refer to the ICAA digital archive and the following texts published by the AIAPE: “La exposición [Amigos de España]” (doc. no. 1191197), “El Arte de Arzádum” (doc. no. 1223148) and “El arte de David Alfaro Siqueiros” (doc. no. 1238628), by Joaquín Torres García, “1er Salón Municipal de Artes Plásticas/Su contenido artístico” (doc. no. 1184568">1184568) and “La pintura de Miguel Angel Pareja” (doc. no. 1223795), by Cipriano S. Vitureira.