Joaquín Torres García (1874–1949) talks about David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974), briefly discussing the painter’s visual art and ideas. JTG no doubt surprised those who considered him to be the antithesis of the Mexican muralist and political activist by saying that he actually liked the man, and explained that they had become friends when they both attended the intellectual tertulias or discussion groups organized by Joan Salvat Papasseit in Barcelona in January 1920. At one point JTG suggested that the idealistic, universalist, atemporal philosophical convictions he had held so far might agree with Siqueiros’s ideas on the contingent diversity of the facts driven by a revolutionary idealism; with one caveat, which is that such an agreement should take place in an abstract space in which aesthetics are subordinate to an ethics that is consistent with a certain humanist concept of History. It would be the concordatio between the duality he once expressed as “eternal man and transient man.” As regards his relationship with Siqueiros, JTG says: “So close during our youth and now, years later, so many differences! And yet, while not being, we are in fact in the same place […]. If he says ‘now’ I can say ‘forever’ and be the same […].”

But, while Siqueiros’s message associates modernity with progress and revolutionary goals, JTG envisions a strictly flat perception of modernity in which he sees nothing but a new formal repertoire and a new way to organize what has been handed down to us by the Great Tradition. Muralism is therefore, in his opinion, a way in which to update that Tradition in terms of a “modern classicism.” The anonymous group work he advocates is also reminiscent of medieval ideas, of a mystical ministry that seeks to create an archaic religious community through art. Despite their differences as regards the concept of the “industrial fresco,” the gregarious idea of a team, and the view of technical and artistic practice as a political instrument—all of which were developed by Siqueiros—the author sees common ground between them in terms of a certain spiritual creed: “People can say what they like about Siqueiros’s work, but they have to admit that it will last. And that is because it is based on faith.” That intransigence in the face of an intuitive conviction of a “Truth” is apparent over and above all the other disagreements, like the substance that unites the protagonists at the point of convergence of the historical avant-gardes in the early twentieth century.

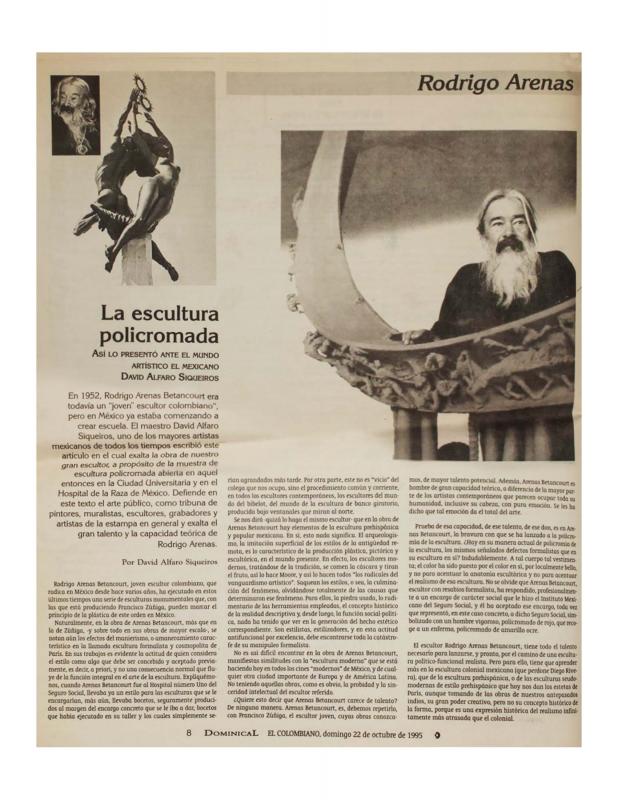

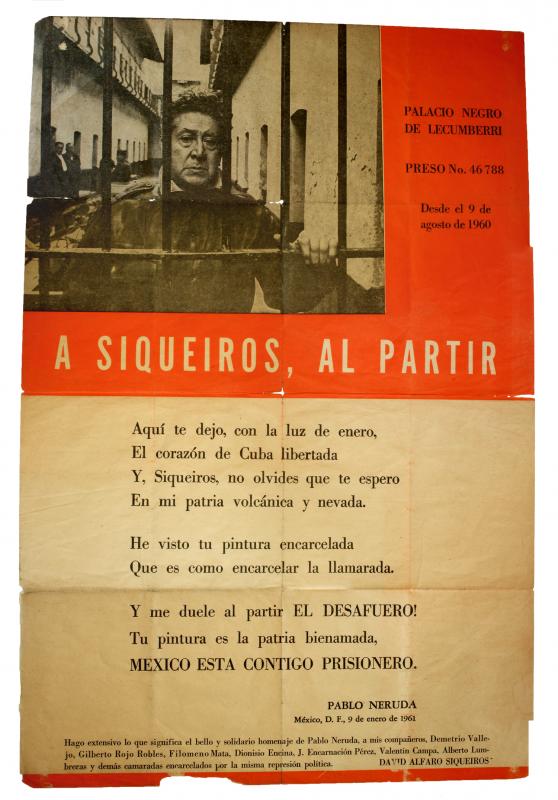

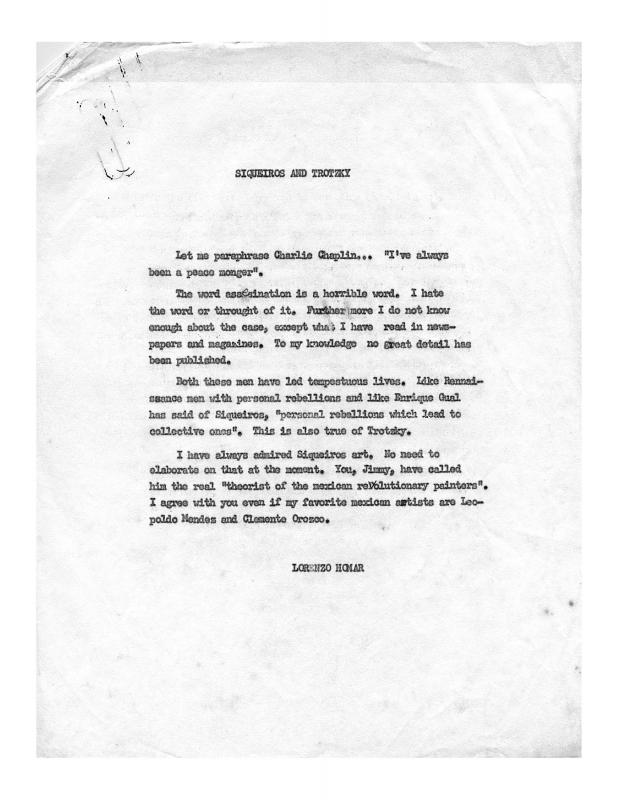

[As complementary reading, see the following texts in the ICAA digital archive: “La escultura policromada: así lo presentó ante el mundo artístico el mexicano David Alfaro Siqueiros” (doc. no. 1100301) and “A Siqueiros, al partir” (doc. no. 864589), both by the Mexican muralist; and by the Puerto Rican printmaker Lorenzo Homar “Siqueiros and Trotzky” (doc. no. 825458)].