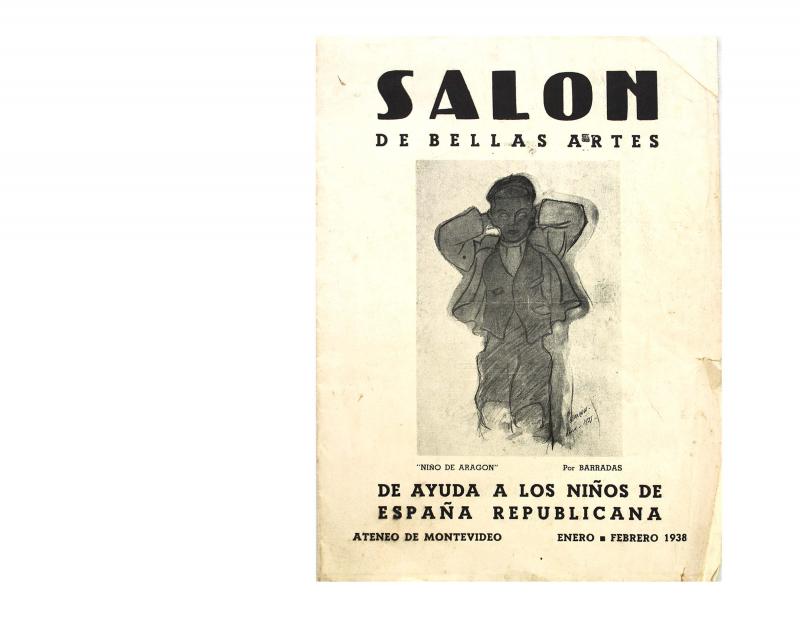

Joaquín Torres García began his speech by talking to the “Friends of Spain.” He deliberately avoided referring to the “martyrs” (it was December 1938, and Franco’s forces had almost won the war), and instead spoke of the “symbolic people,” a term that looked beyond the military conflict to address the idea of the “universal man” that underpinned his works and that, in his opinion, those people embodied. The exhibition at the Ateneo did not dwell on local aesthetic differences; it was an event that reflected a sense of solidarity with people who “rise up to defend what defines mankind against what it used to be, since this is also a world of inferior beings.” Known for his tough controversial views and his regular lectures about art in which he spares no criticism of peers he describes as “figurative painters” and exponents of “social realism,” JTG became, on this occasion, a homo politicus who recast his theory of the Universal Abstract Man as a theory that specifically referred to a universal historical man who represents a “Humanity [that] awakens from its lethargy to reclaim its dignity as a superior being.” The ontological essence of that abstract “Humanity” is close to the idea of Unanism that was introduced to Montevideo by Jules Romains (1885–1972). But JTG denied that his speech was in any way politically charged (in the limiting sense involved in partisan politics or factious disagreements), anticipating provincial suspicions about such matters and repeating that “There is just one issue here: a profound awareness has awoken” [on that subject, see in the ICAA digital archive the article by the Ateneo de Montevideo (Organizing Committee) “Salón de Bellas Artes de ayuda a los niños de España Republicana” (doc. no. 1186907)].

This is an especially important document—which has barely been circulated in the years since it was written—in which JTG expresses his ideas as a forceful philosophical, and above all moral, statement that rises with uncommon messianic force above the well-worn political-partisan discourse being bandied about in Uruguay at the time.

[For additional information, see the controversial essay, written in 1934 by Norberto Berdía “El arte de Torres García” (doc. no. 1208154)].