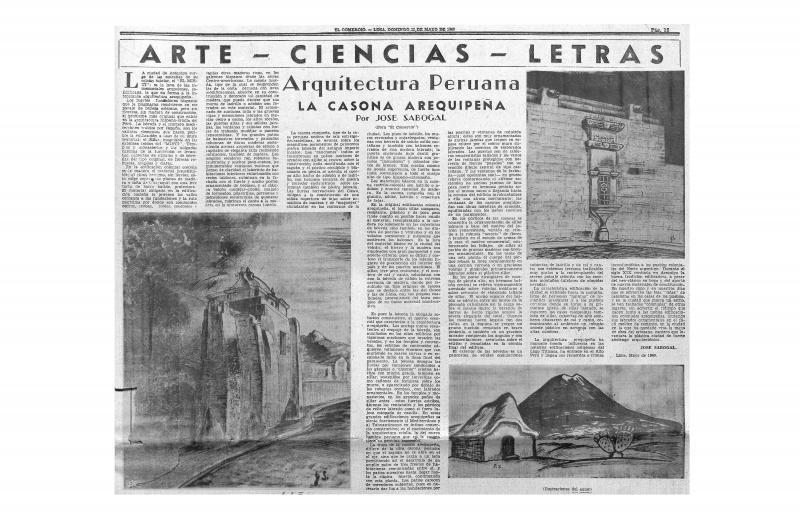

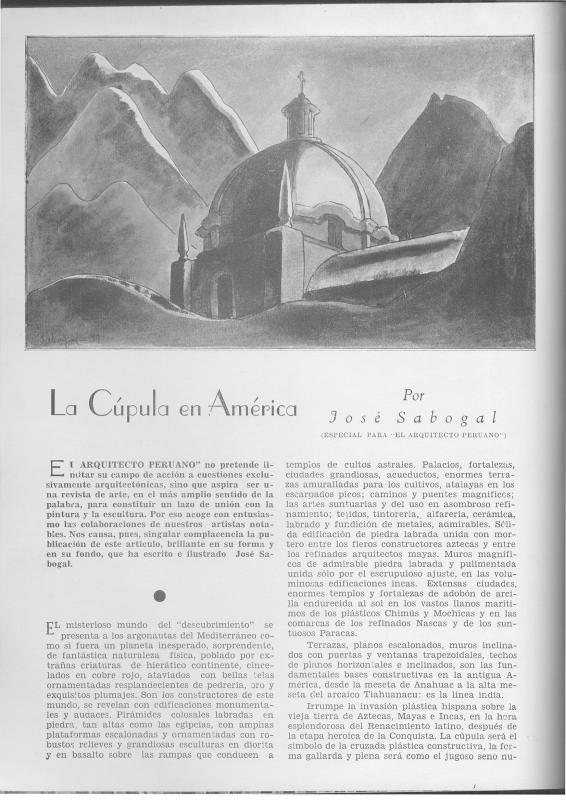

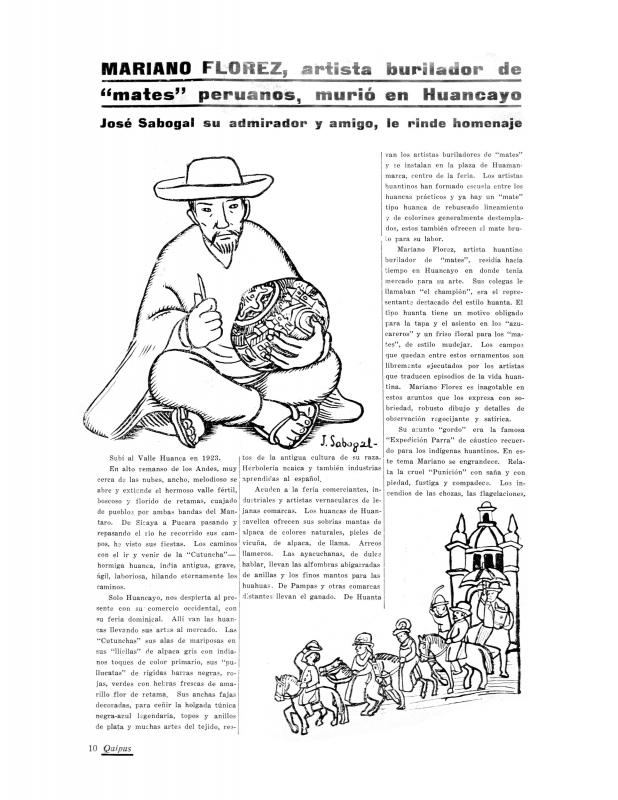

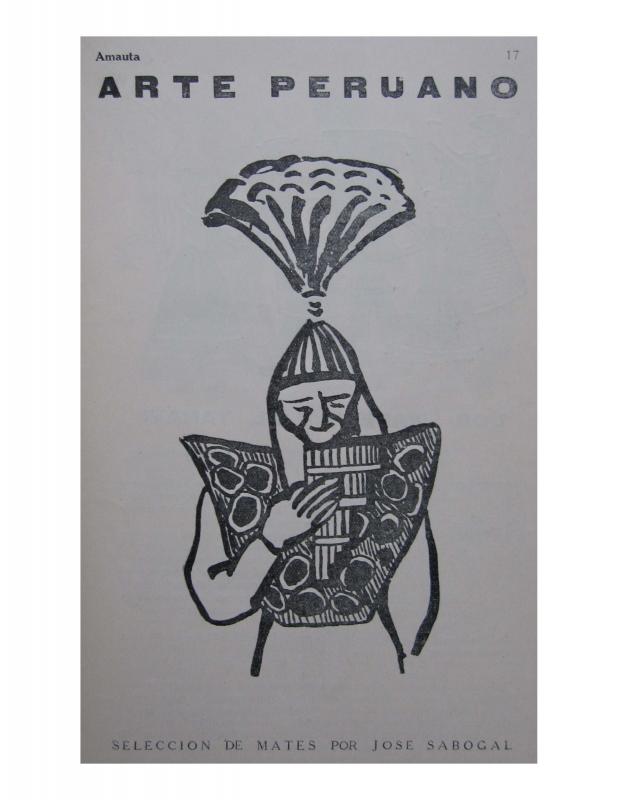

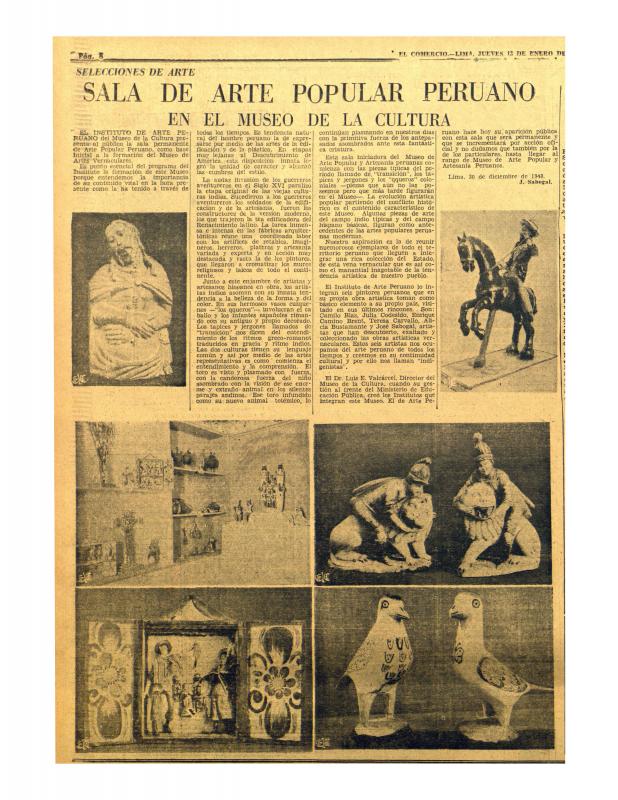

This is the open letter addressed to the then-president of Peru, Manuel Prado Ugarteche, signed by professors, administrative staff, students and ex-students of the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes, and supported by artists and intellectuals. The list of signatories includes distinguished artists who are members of the Indigenist movement, including: Camilo Blas, Julia Codesido, Teresa Carvallo, Enrique Camino Brent, Alicia Bustamante, Celia Bustamante, Leonor Vinatea Cantuarias, Cota Carvallo de Núñez, and Carmen Saco. Other signatories include artists and intellectuals associated with the Indigenist movement, such as Miguel Baca Rossi, Carlos Bernasconi, Luisa Castañeda León, Luis Ccosi Salas, Pedro Rojas Ponce, Mario Urteaga, José María Arguedas, César Arróspide de la Flor, Antonino Espinosa Saldaña, José Eulogio Garrido, Mercedes Gallagher de Parks, Arturo Jiménez Borja, Elvira Luza, Manuel Moncloa, Estuardo Núñez, Clemente Palma, Carlos Raygada, Carlos Sánchez Málaga, and Luis E. Valcárcel. The letter was also signed by artists who subsequently moved away from the Indigenist movement, such as Ricardo Grau and Víctor Humareda. Indigenist painting flourished in Peru from the 1920s to the 1940s as part of a broader movement that sought to redefine Peruvian identity in terms of indigenous elements. Although at some points it was entirely focused on the “indigenous” story and the glorious Inca past that also championed a mestizo identity portrayed as a result of the integration of “native” and “Hispanic” cultures. The main ideologue and unchallenged leader of the Indigenist movement in the visual arts was José Sabogal (1888–1956), whose profound interpretation of the concept of “being rooted” was deeply influenced by regional art movements in Spain (exemplified by Ignacio Zuloaga [1870–1945], among others) and in Argentina (Jorge Bermúdez [1883–1926], to mention just one); Sabogal spent a great deal of time in these countries during his formative years. When he returned to Peru in late 1918, he settled in Cuzco where he produced about forty oil paintings of people and scenes of the city; these works were subsequently shown in Lima (1919) at an exhibition that is considered the formal beginning of Indigenist painting in Peru. Sabogal’s second solo exhibition at the Casino Español (1921), established his reputation. He joined the faculty at the new Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in 1920, where he was eventually appointed director (1932–43). There he trained a group of painters who joined the Indigenist movement: Julia Codesido, Alicia Bustamante (1905–1968), Teresa Carvallo (1895–1988), Enrique Camino Brent (1909–1960), and Camilo Blas (1903–1985). In the mid-1930s, a powerful movement emerged to oppose the Indigenist style—which was perceived as official and exclusive—and eventually, in 1943, Sabogal was dismissed from the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes. Supporters of Indigenism viewed this move as unjust, and rallied to the painter’s defense in letters, newspaper articles, and social events. [There are many articles about this artist, including the following written by Sabogal himself: “Arquitectura peruana: la casona arequipeña (doc. no. 1173340); “La cúpula en América” (doc. no. 1125912); “Mariano Florez, artista burilador de "mates" peruanos, murió en Huancayo: José Sabogal su admirador y amigo, le rinde homenaje” (doc. no. 1136695); “Los mates burilados y las estampas del pintor criollo Pancho Fierro” (doc. no. 1173400); “Los 'mates' y el yaraví” (doc. no. 1126008); “La pintura mexicana moderna” (doc. no. 1051636); and “Sala de arte popular peruano en el Museo de la Cultura : selecciones de arte” (doc. no. 1173418)].