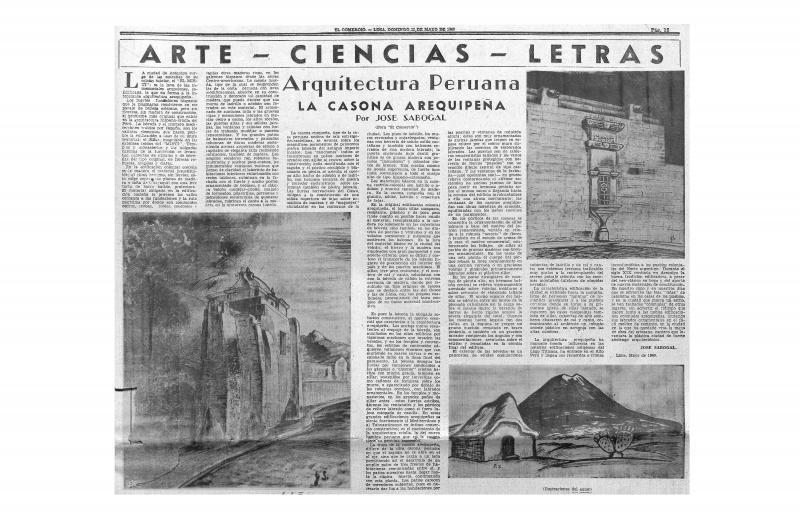

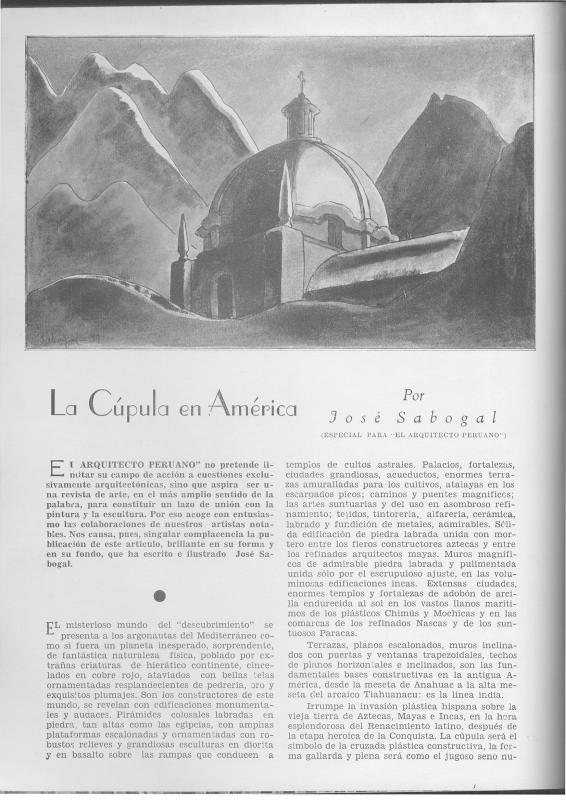

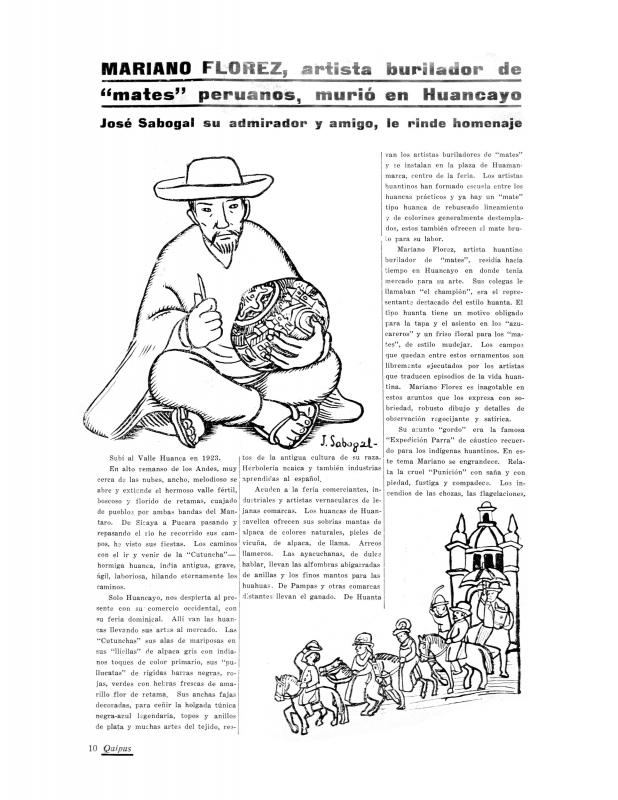

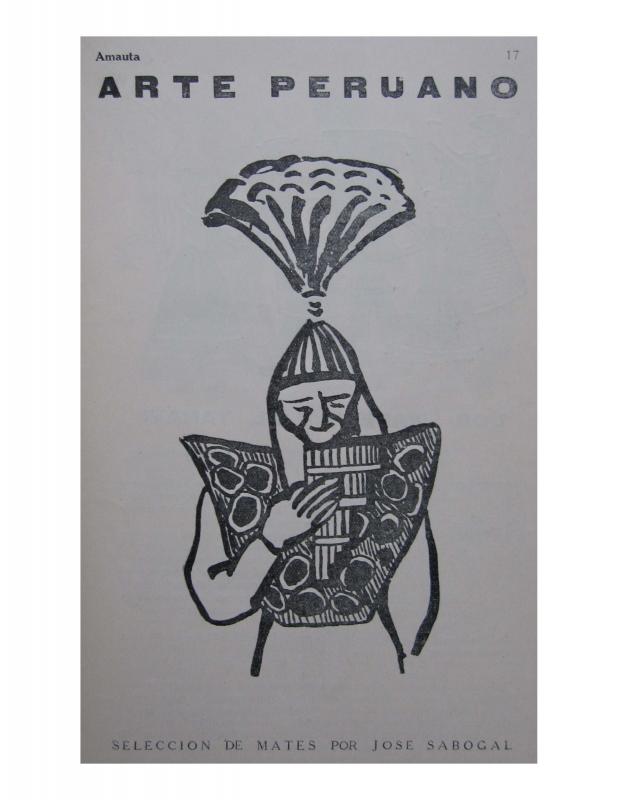

These are the observations made by José Sabogal on the opening of the permanent installation of Arte Popular Peruano at the Museo de la Cultura Peruana, published by the Instituto de Arte Peruano, where he served as director (Lima, December 1948). Sabogal and his group of followers pursued one topic with special interest, the study and re-evaluation of folk arts. They traveled through the country, meeting with native and mestizo artisans, whose names and works began to circulate in Lima, incorporating this art into the official Peruvian arts. Sabogal likewise defined folk art as the paradigm of the “real Peruvian art,” because it was a mestizo art, the blending of indigenous and Spanish creativity. In his last period, Sabogal dedicated particular attention to the concept of “mestizaje” [miscegenation] as the element that defined the nation’s art, as in his judgment it was present not only in folk arts but also in vice-regal architecture and in the work of nineteenth century painter Pancho Fierro. On this topic he published texts such as “La cúpula en América” (1939), “Arquitectura peruana. La casona arequipeña” (1940), “Los mates burilados y las estampas del pintor criollo Pancho Fierro” (1943), “Pintura mural y Arequipa arquitectónica” (1944), and “Mariano Florez, artist who engraved Peruvian ‘mates,’ died in Huancayo. José Sabogal, his friend and admirer, pays homage” (1932) [texts reproduced for this project]. As director of the Instituto de Arte Peruano at the Museo de la Cultura Peruana (which he took up again in 1946), Sabogal proposed as fundamental aspects of the work the creation of a registry of vice-regal architecture and the collection and study of folk art objects for incorporation into the Museo de Artesanía y Artes Populares [see: Sabogal, José. Instituto de Arte Peruano. Informe sobre sus activiades, ca. 1950. Archivo IAP, MNCP]. The indigenist art movement was at its peak in Peru between the 1920s and 1940s. It was part of a broader movement within Peruvian society: the redefining of the national identity through native elements. Although at times it focused on the revaluation of “the indigenous” and Incan past, which was considered glorious, it also took up the defense of a mestizo identity as the integration of “the native” and “the Hispanic.” The principal ideologue and undisputed leader of indigenous art was José Sabogal (1888–1956), who believed a deep awareness of their “roots” decisively influenced the regionalist trends of art in both Spain (Ignacio Zuloaga [1870–1945], among others) and Argentina (Jorge Bermúdez [1883–1926], to mention one of them); Sabogal had spent his formative years in these countries. When he returned to Peru at the end of 1918, he settled in Cuzco, where he created nearly forty paintings about people and scenes of the city, later exhibited in Lima (1919). This exhibition is considered the beginning of the indigenous art movement in Peru. His second individual show in Lima occurred at the Casino Español (1921), and it solidified his reputation. In 1920, Sabogal joined the faculty of the new Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes, later serving as its director (1932–43). There he formed a group of painters who adhered to the indigenous art movement, such as Julia Codesido, Alicia Bustamante (1905–68), Teresa Carvallo (1895–1988), Enrique Camino Brent (1909–60) and Camilo Blas (1903–85). [There are a great number of texts on this artist in the ICAA digital archive, including the following written by Sabogal himself: “Arquitectura peruana: la casona arequipeña (doc. no. 1173340); “La cúpula en América” (doc. no. 1125912); “Mariano Florez, artista burilador de ‘mates’ peruanos, murió en Huancayo: José Sabogal su admirador y amigo, le rinde homenaje” (doc. no. 1136695); “Los mates burilados y las estampas del pintor criollo Pancho Fierro” (doc. no. 1173400); “Los ‘mates’ y el yaraví” (doc. no. 1126008); and “La pintura mexicana moderna” (doc. no. 1051636)].