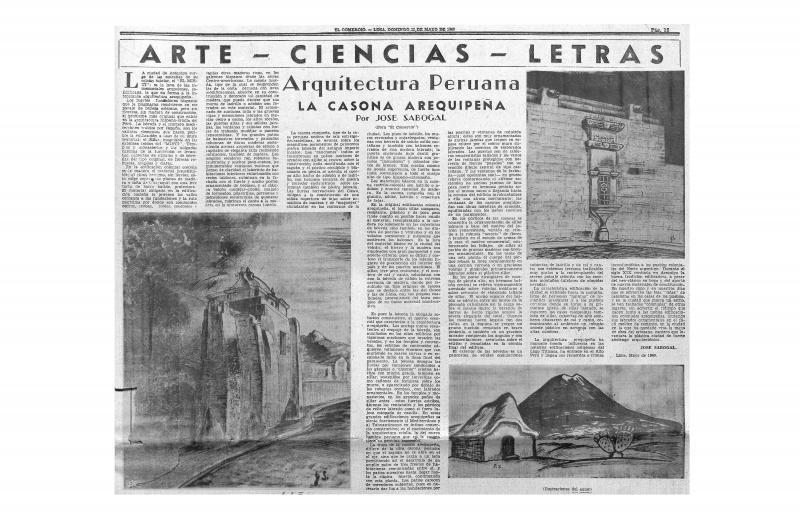

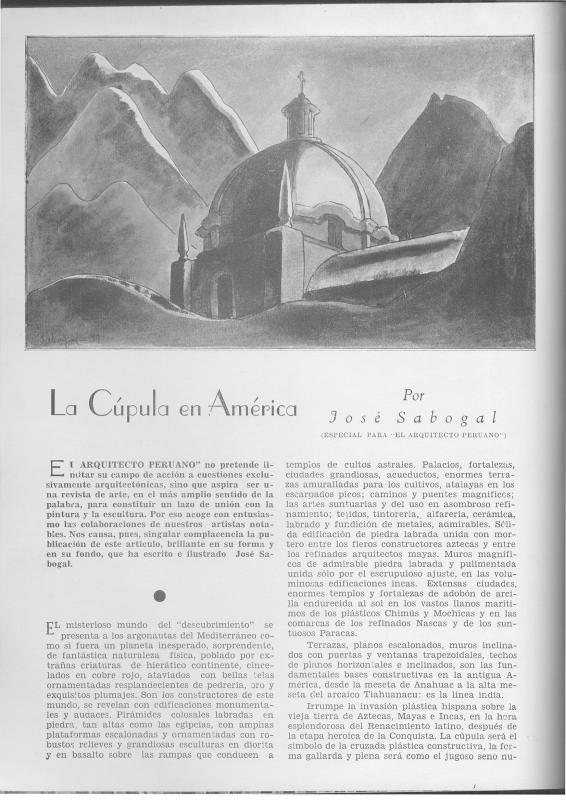

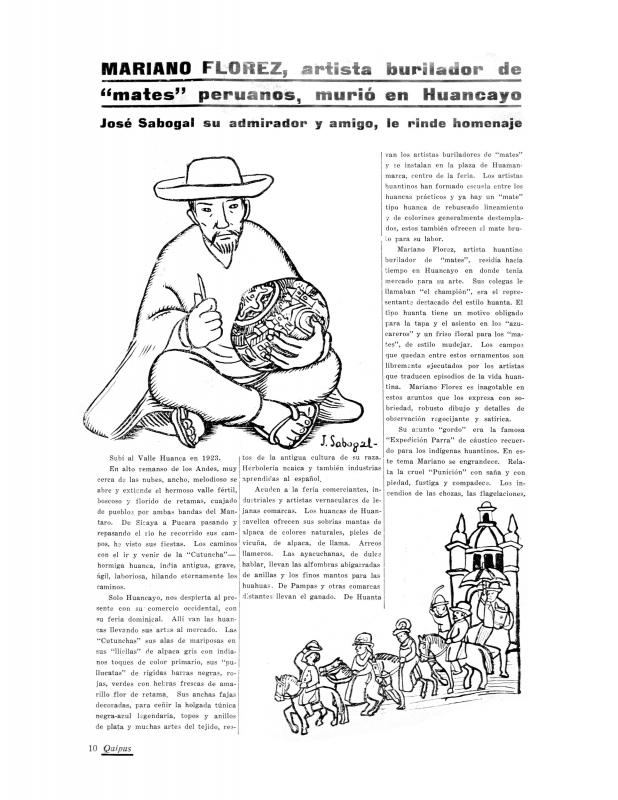

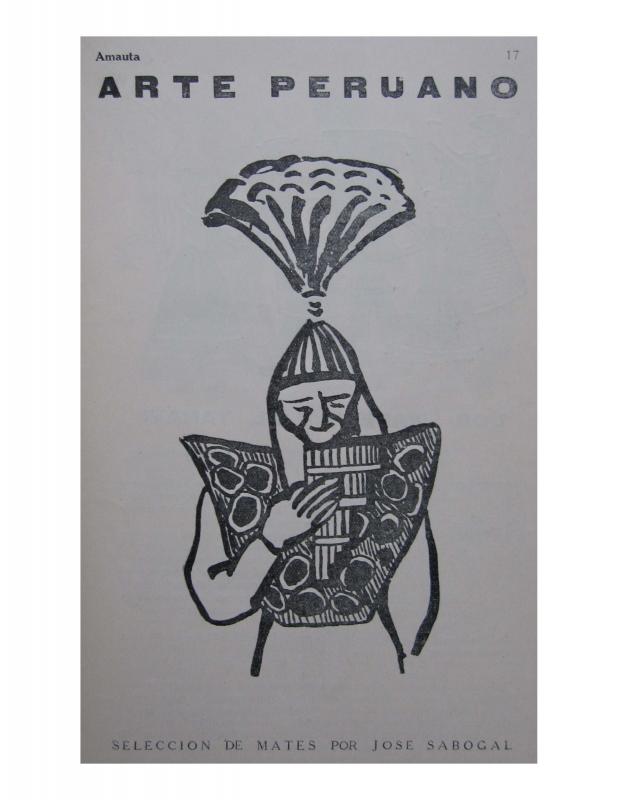

This is a chapter from Perú: Problema y posibilidad, the book by the noted Peruvian historian Jorge Basadre (1903–1980) about the work of José Sabogal (1888– 1956), the founder of Peruvian indigenist painting. Indigenist painting flourished in Peru from the 1920s to the 1940s as part of a broader movement that sought to redefine Peruvian identity in terms of indigenous elements. Although at some points it was entirely focused on the “indigenous” story and the glorious Inca past that also championed a mestizo identity portrayed as a result of the integration of “native” and “Hispanic” cultures. The main ideologue and unchallenged leader of the Indigenist movement in the visual arts was José Sabogal (1888–1956), whose profound interpretation of the concept of “being rooted” was deeply influenced by regional art movements in Spain (exemplified by Ignacio Zuloaga [1870–1945], among others) and in Argentina (Jorge Bermúdez [1883–1926], to mention just one); Sabogal spent a great deal of time in these countries during his formative years. When he returned to Peru in late 1918, he settled in Cuzco where he produced about forty oil paintings of people and scenes of the city; these works were subsequently shown in Lima (1919) at an exhibition that is considered the formal beginning of Indigenist painting in Peru. Sabogal’s second solo exhibition at the Casino Español (1921), established his reputation. He joined the faculty at the new Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in 1920, where he was eventually appointed director (1932–43). There he trained a group of painters who joined the Indigenist movement: Julia Codesido, Alicia Bustamante (1905–1968), Teresa Carvallo (1895–1988), Enrique Camino Brent (1909–1960), and Camilo Blas (1903–1985). This text is taken from Perú: Problema y posibilidad (Lima, 1931), the book by the noted Peruvian historian Jorge Basadre (1903–1980). The author advises that in view of the challenging circumstances Peru is currently facing, the country must review its past—and the patchwork of partial and imperfect threads that have woven together the failed fabric of its present—to find the foundation for its future. Basadre was against some of the locally-focused solutions that were rife in the early decades of the twentieth century (Inca-ism or colonialism) that he thought overvalued one part of Peruvian history, and instead advocated a more comprehensive approach. In the twelfth chapter of his book he discusses the country’s artistic situation. Basadre sees a solution in Sabogal’s work, in which he detects a broader vision for Peru: one that is inspired by a synthesis of the country’s various threads and favors neither the sumptuousness of the Inca Empire nor the attractive qualities of the colonial period. A new edition of this book, published in 1978, included a facsimile of the 1931 text with an appendix entitled “Some reconsiderations, forty-seven years later.” In the revised version of chapter twelve, Basadre notes omissions, such as the reference to artistic expression from the pre-Hispanic period—such as pottery or ceramics, textiles, and architecture—and the changes that occurred in some genres during the Viceroyalty era (sculpture, painting, costumes, music, and dance). He lauds the attempts made by Sabogal and his students to reclaim the country’s traditional art. [There are many articles about this artist in the ICAA digital archive, including the following written by Sabogal: “Arquitectura peruana: la casona arequipeña (doc. no. 1173340); “La cúpula en América” (doc. no. 1125912); “Mariano Florez, artista burilador de "mates" peruanos, murió en Huancayo: José Sabogal su admirador y amigo, le rinde homenaje” (doc. no. 1136695); “Los mates burilados y las estampas del pintor criollo Pancho Fierro” (doc. no. 1173400); “Los 'mates' y el yaraví” (doc. no. 1126008); “La pintura mexicana moderna” (doc. no. 1051636); and “Sala de arte popular peruano en el Museo de la Cultura : selecciones de arte” (doc. no. 1173418)].