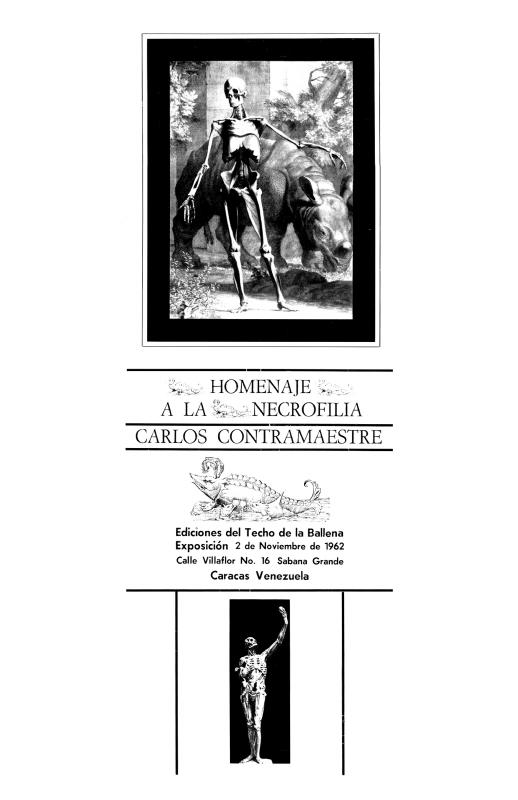

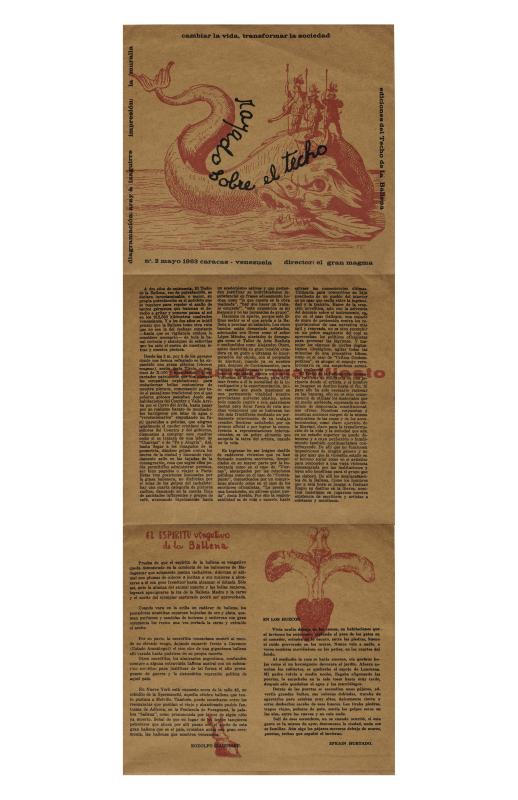

The poet and critic Francisco Pérez Perdomo (1930?2013) wrote this introduction to Asfalto-Infierno, the book by Adriano González León with photographs by Daniel González. The book was published in 1963 by El Techo de la Ballena (Caracas, 1961–1968), the group to which they all belonged. The subject of the book—one of the first manifestos devoted to Caracas’ urban culture—is the “crowd in the city,” so hard to find in Venezuelan literature and pop culture. The book describes the chaos, the sense of being rootless and adrift, and the anarchy of a city that experienced explosive and unequal growth fueled by the country’s fabulous oil riches. The combination of disciplines—literature and photography—was a signature feature of El Techo de la Ballena’s publications and exhibitions. The introduction outlines the contents of the publication. As often happened in items written by members of El Techo de la Ballena group, Pérez Perdomo describes the book as being about the opposite of the things it sought to subvert: Venezuelan patriotic values, tacky photographs, false glories, and romantic tradition. The goal of the book, therefore, is to challenge traditional values, advocating a new idea that demands new forms of expression. The author explains that North American Beat poetry inspired the text in the book and influenced González León’s broken syntax and “out of control language.” González’s crude and “belligerent” photographs are unstinting in their portrayal of reality. Images and text engage in a balanced dialogue in which neither discipline overshadows the other. El Techo de la Ballena was a group of visual artists and writers from the Venezuelan avant-garde who (from 1961 until 1968) combined a range of different disciplines—visual art, poetry, photography, film, and action art, among others—to create a revolutionary form of art that, in their opinion, challenged and contradicted every traditional socio-cultural value during the decade of greatest political violence that Venezuela had ever experienced. The group saw themselves as the artistic expression of that chaotic period, and viewed guerrilla warfare, intellectual leftist ideas, repression, and cities devastated by the forced and accelerated developmental model of the country’s nascent democracy during the presidency of Rómulo Betancourt (1959–64) as their frame of reference. The visual artists in the group embraced informalism as their aesthetic, to which they added a potent shot of aggressiveness to counter the values of geometric abstraction, traditional landscape painting, and even social realism, and adopted a strategy that was subversive, provocative, irrational, and surrealistic. The group produced numerous publications—including the three issues of the magazine Rayado sobre el Techo—and exhibitions. [To read other articles written by members of El Techo de la Ballena group, see in the ICAA digital archive by Adriano González León “Homenaje a la necrofilia” (doc. no. 1097543); also by Adriano González León “Tercer manifiesto: ¿Por qué la ballena?” (doc. no. 1097576); by Juan Calzadilla and Carlos Contramaestre “Los tumorales I y II” (doc. no. 1097559); and by Ángel Rama the prologue known as “Terrorismo en las artes” (doc. no. 1097527). See also, by El Techo de la Ballena (untitled) “[Establecer una frontera entre lo cursi y lo pavoso...]” (doc. no. 1059586); “Para la restitución del magma” (doc. no. 1060710); “Las ‘Instituciones de cultura’ nos roban el oxígeno, afirman” (doc. no. 1060199); Rayado sobre el techo. Cambiar la vida, transformar la sociedad (doc. no. 1060254); and “Segundo Manifiesto” (doc. no. 1057677)].