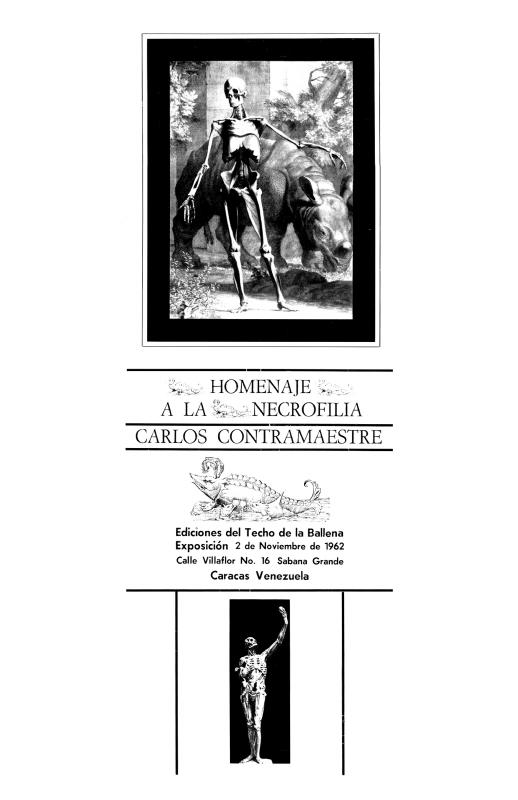

The first part of the text for the exhibition Los Tumorales was written by poet and visual artist Carlos Contramaestre (1933–96) and the second by Venezuelan poet, critic, and draftsman Juan Calzadilla (b. 1931). Both parts make use of the surrealist and morbid humor characteristic of El Techo de la Ballena. The show took place at the Galería El Techo de la Ballena in Caracas and at the Galería 40 Grados a la sombra in Maracaibo in 1963. The section of the text by Contramaestre, who was a medical doctor as well as an artist, clearly evidences his obsession with the decomposition and degeneration of matter—a concern efficaciously engaged by the Informalist aesthetic to which he subscribed. Contramaestre had already laid the basis for the visual discourse he would pursue during the El Techo de la Ballena years, mostly in the polemic exhibition Homenaje a la Necrofilia (1962). In the second part of the text, Calzadilla attempts to shed light on the meaning of the allegories Contramaestre employs in both his text and in the works in the exhibition. What Contramaestre is addressing, Calzadilla argues, is the decrepit, obsolete, and corrupt nature of Venezuelan society and the State. This text was reproduced in Ángel Rama’s Antología de El Techo de la Ballena (Caracas: Fundarte, 1987). At the bottom of this text, there is a mistake in the date, since the exhibition Los Tumorales took place in 1963, not in 1967.

The Techo de la Ballena was an avant-garde group of Venezuelan visual artists and writers active from 1961 to 1968. They combined different disciplines (visual art, poetry, photography, film, actions, and others) to create revolutionary art that questioned and disputed traditional social and cultural values in the context of a decade riddled with political violence, which they mirrored in the realm of art. The framework for the group’s activity was the guerrilla movement, the formulations of the intellectual left, political repression, a city deformed by accelerated and forced growth under the developmentalist model embraced by a recent democracy under Rómulo Betancourt (president from 1959-64). Their aesthetic was tied to Informalism with a strong dose of aggression to contest the values of abstract geometry, traditional landscape art, and even social realism; their strategy embraced subversion and provocation, the irrational and the surrealist. They published a good many texts—among them, three issues of the magazine Rayado sobre el techo—and organized a good many exhibitions. The members of the group included Venezuelan artists Carlos Contramaestre, Juan Calzadilla, Caupolicán Ovalles, Edmundo Aray, Francisco Pérez Perdomo, Salvador Garmendia, Adriano González León, Fernando Irazábal, Daniel González, Gabriel Morera, Gonzalo Castellanos, Perán Erminy; and foreign artists Dámaso Ogaz (from Chile) and J. M. Cruxent, Ángel Luque, and Antonio Moya (from Spain).

For other texts by members of the El Techo de la Ballena group, see Adriano González’s “Homenaje a la necrofilia” (doc. no. 1097543), which introduces the work by Contramaestre included in the exhibition of the same name held in 1962 at the Galería El Techo de la Ballena, Caracas; and González León’s “Tercer manifiesto: ¿Por qué la ballena?” (doc. no. 1097576), which describes the nature of the group and its activities.

Homenaje a la Necrofilia was the most controversial of the exhibitions organized by the group. It was met with rage and condemnation on the part of the cultural milieu and the general public (see the article “Declara Pedro Centeno Vallenilla: ‘Defensores del folleto con aberraciones sexuales obedecen al complejo del salvaje que goza comiendo inmundicias...’” (doc. no. 865836).