El Techo de la Ballena was a group of visual artists and writers from the Venezuelan avant-garde who (from 1961 until 1968) combined a range of different disciplines—visual art, poetry, photography, film, and action art, among others—to create a revolutionary form of art that, in their opinion, challenged and contradicted every traditional socio-cultural value during the decade of greatest political violence that Venezuela had ever experienced. The group saw themselves as the artistic expression of that chaotic period, and viewed guerrilla warfare, intellectual leftist ideas, repression, and cities devastated by the forced and accelerated developmental model of the country’s nascent democracy during the presidency of Rómulo Betancourt (1959–64) as their frame of reference. The visual artists in the group embraced informalism as their aesthetic, to which they added a potent shot of aggressiveness to counter the values of geometric abstraction, traditional landscape painting, and even social realism, and adopted a strategy that was subversive, provocative, irrational, and surrealistic. The group produced numerous publications—including the three issues of the magazine Rayado sobre el Techo—and exhibitions. Members of the group included the Venezuelans Carlos Contramaestre, Juan Calzadilla, Caupolicán Ovalles, Edmundo Aray, Francisco Pérez Perdomo, Salvador Garmendia, Adriano González León, Fernando Irazábal, Daniel González, Gabriel Morera, Gonzalo Castellanos, and Perán Erminy, as well as artists from other countries who were living in Venezuela at the time, such as the Chilean Dámaso Ogaz and the Spaniards J. M. Cruxent, Ángel Luque, and Antonio Moya.

“Change life, transform society,” the exhortation that appeared on the cover of the second issue of the magazine Rayado sobre el Techo, expressed the key objectives of this edition, and referred to the main ideas that inspired the members of the group. Transform the world, as demanded by Marxist doctrine, and change life, as proclaimed by Arthur Rimbaud. Both were used by André Breton and the Surrealists (in the manifestos they published in the mid-1920s) and, four decades later, were adopted by student movements around the world in the wake of the Paris uprising in May ’68. These words captured the fundamental goal of the members of “La Ballena.” Unlike the first issue of the magazine, the articles in this one were longer and more focused, expressing the group’s main interests: Surrealism and freedom of spirit, critical Marxism and urgent social change. The articles and essays addressed the overlapping of literature and the visual arts, and discussed political, aesthetic, and social events. An experimental version of a variety of discourses coupled with a Surrealist approach influenced the formal elements in these works.

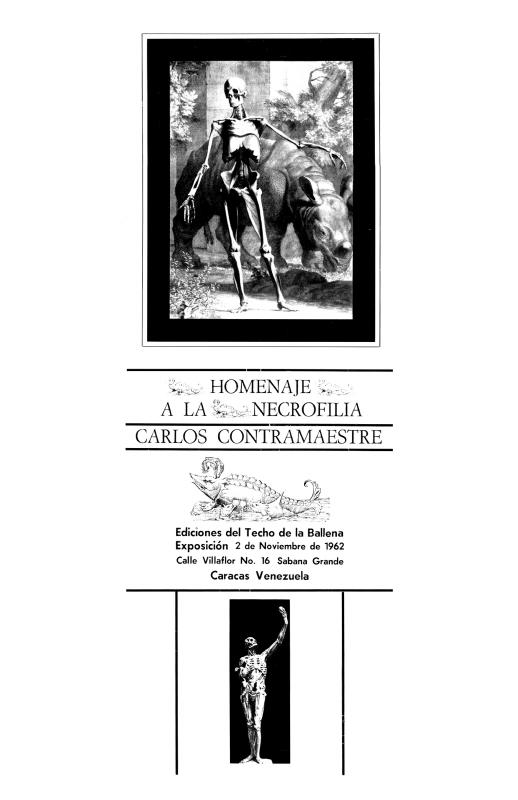

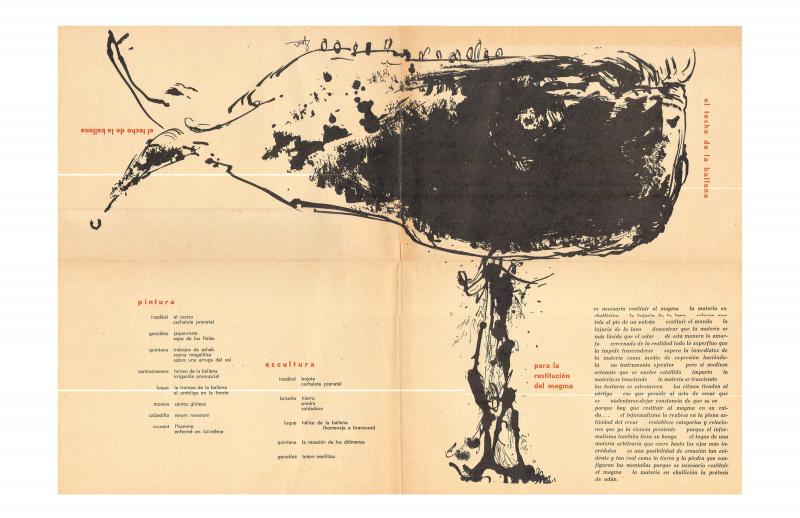

[To read other articles written by members of El Techo de la Ballena, see in the ICAA digital archive by Adriano González León “Homenaje a la necrofilia” (doc. no. 1097543), his introduction to Carlos Contramaestre’s work at the exhibition Homenaje a la necrofilia, 1962; also by González León “Tercer manifiesto: ¿Por qué la ballena?” (doc. no. 1097576); by Juan Calzadilla and Contramaestre “Los tumorales I y II” (doc. no. 1097559), in which they introduce the latter’s exhibition Los Tumorales, in 1963; by Francisco Pérez Perdomo (untitled) “[Hay ciertos rostros de la ciudad…]” (doc. no. 1060288); and by Ángel Rama the prologue known as “Terrorismo en las artes” (doc. no. 1097527). See also by El Techo de la Ballena (untitled) “[Establecer una frontera entre lo cursi y lo pavoso…]” (doc. no. 1059586); “Para la restitución del magma” (doc. no. 1060710); “Las ‘Instituciones de cultura’ nos roban el oxígeno, afirman” (doc. no. 1060199); Rayado sobre el Techo no. 1, editorial (doc. no. 1142155); and “Segundo Manifiesto” (doc. no. 1057677)].