July 26, 2022

Luz Muñoz, Chief Cataloguer for the ICAA, was among the first in her home country to think about how to systematize access to Chilean contemporary art documents. When local records are few and fragmentary, Muñoz recognized that a “digital copy can preserve and safeguard our heritage.” In this two-part post she reflects on the early history and collaborative process behind the ICAA’s Documents Project. Click here to read Part II.

In phase one, which spanned a period of several years beginning in 2003, the project addressed the challenge of working with institutions and specialized research teams in every Latin American country and with researchers of Latino sources in the United States. The selection of documents in participating countries was handled by local researchers working in teams led by a coordinator. These groups of researchers were associated with a research or academic institution in their country, with which the ICAA worked according to the terms of a collaborative agreement on the Documents Project.

Similarly, the project’s editorial team included representatives from each participating country, who worked with ICAA Director Mari Carmen Ramírez and her team at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

***

In Latin America, and specifically in Chile, strategies that were compatible with local conditions were used in the selection of documents. The search for and selection of the documents was driven by editorial considerations and definitions that had been established in advance by the specialists working on the editorial team.

The field work for the project involved overcoming challenges and difficulties; the first part of the process was accomplished thanks to the efforts, knowledge, and networks of local researchers. Many difficulties had to be addressed as we searched for documents, including the precarious nature of Chilean systems and institutions at that time, the absence of policies regarding existing archives stored at central organizations, and—of far greater concern—the lack of political will at local institutions and governments.

The reality was that local art history documentation records were few and fragmentary. Another problem was the lack of resources needed for libraries and documentation centers to process the materials they collected, which were frequently based on statements made by the professionals themselves. It could therefore take years for documents and records to be removed from the boxes in which they usually arrived at these institutions. During that time, of course, users could not access the materials.

Given that situation, the Document Project’s researchers often resorted to documents and records held in the private archives of artists, critics, or authors if they were still living or, if not, with luck, held by a family member of the deceased.

Archives of this kind were already attracting interest throughout the Americas at that time, but in Chile that trend had only just begun.

In 2000, when I worked as the assistant to the curator, Justo Mellado, on the exhibition Chile 100 años, Tercer periódo, I was responsible for the documentation involved in the project. That experience gave me the opportunity to see firsthand the difficulties involved in accessing the documents and records we needed for the exhibition. It also made me realize that Chilean art history documents were widely dispersed. We set up an archives room at the exhibition, which was something new in contemporary art exhibitions at the time.

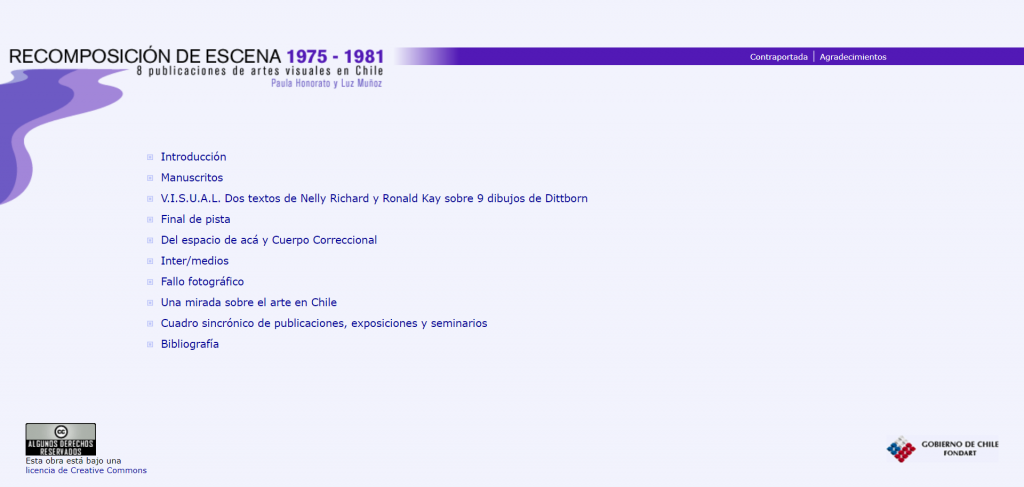

I was among those who first started thinking about how to systematize Chilean contemporary art documents and records. Paula Honorato and I met during Chile 100 años, when she was a member of the exhibition’s curatorial team. We then worked together to create a website [textosdearte.cl] that was a first attempt at systematizing Chilean art texts from the period 1973-2000. It was a relational data base, open to the public, financed with cultural funds supplied by the Chilean government. Paula and I immediately started a second project along similar lines, a collection of historical documents that became the Reconstitución de Escena 1975-1981; 8 Publicaciones de artes visuales en Chile [Scene Reconstruction 1975-1981; 8 Publications on the Visual Arts in Chile]. Those projects caused quite a stir in the community and among specialists in the field; it was a first step. After that, I was asked to develop and co-create the first Centro de Documentación de las Artes Visuales en Chile [Center for the Documentation of the Visual Arts in Chile], working with Isabel García. The Center was eventually opened at the Centro Cultural de la Moneda in July 2006.

The ICAA Documents Project began in Chile in 2004. The first research and selection team was made up of Justo Mellado, as coordinator, and Alberto Madrid, Patricio Muñoz Zarate, Paula Honorato, José de Nordenflycht, and myself. Two years later Alberto Madrid took over as coordinator, and Paulina Varas joined the project under the auspices of the Universidad de Playa Ancha. I worked with the Chilean team until late 2006 when I went to Geneva to do postgraduate curatorial studies.

During the final phase of the project in Chile, over the last three years (2019-2022), I have been working as an ICAA coordinator; the researchers Sebastián Valenzuela and Mariairis Flores, from Fundación AMA, also collaborated on the project.

Translated by Tony Beckwith