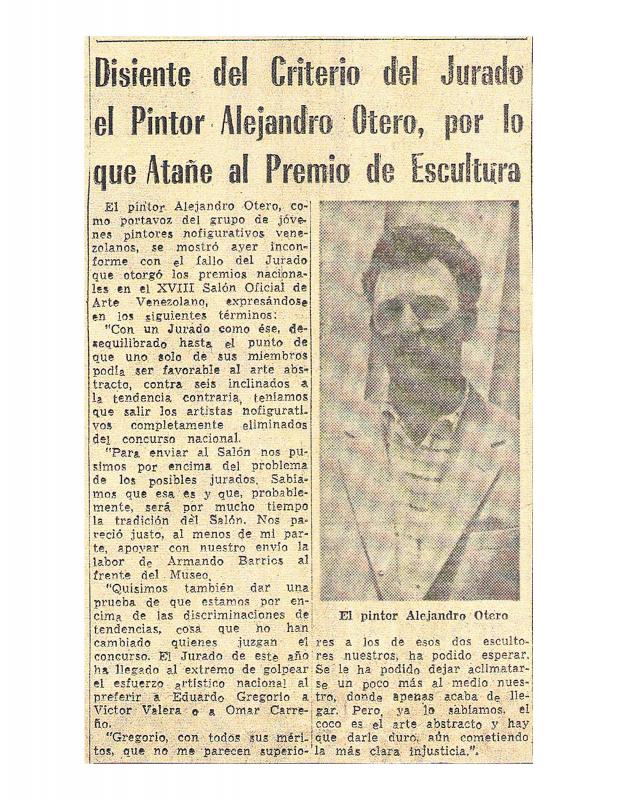

This article is one of the first of a series that Miguel Otero Silva (1908−1985) devoted to the critique of abstract art and in defense of social realism and landscape art. [Refer to the ICAA digital archive to access the above mentioned series of articles: “I: Un relato necesario: Conceptos concretos sobre la pintura abstracta” (doc. no. 855537); “II: Una división sin contenido plástico: Conceptos…” (doc. no. 855992); “III: Aparición y desarrollo del abstraccionismo: Conceptos…” (doc. no. 856012); “IV: Ubicación social del abstraccionismo: Conceptos…” (doc. no. 856031); “V: Sobre el mundo interior de los abstraccionistas: Conceptos… (doc. no. 856050); VI: “El regreso a lo funcional y lo decorativo: Conceptos…” (doc. no. 856069); VII: Formas nuevas y sinceridad: Conceptos…” (doc. no. 856923) and VIII: “Orientaciones de una nueva pintura: Conceptos…” (doc. no. 856942)]. In this particular article, as a result of a clear disagreement with the abstract artist Alejandro Otero (1921−1990), Miguel Otero Silva, suggested three reasons (a humanistic, a philosophical, and an aesthetic reason) that he felt justified the award granted for painting and sculpture by the jury of the XVIII Salón Oficial de Arte Venezolano in 1957. In fact, the artist only questioned one of the awards [refer to the ICAA digital archive (doc. no. 813821) for the anonymous text “Disidente del criterio del jurado el pintor Alejandro Otero, por lo que atañe al Premio de Escultura”], because the then-director of the museum and member of the jury, Armando Barrios (given the “painter’s” award) had belonged to the group Los Disidentes, an avant-garde Venezuelan art group begun in Paris (1950). (1) The “humanistic” reasons put forward by the journalist were nothing other than the uncompromising defense of the traditional institutions and the Escuela de Artes Plásticas y Aplicadas, the Museo de Bellas Artes, the Dirección de Cultura del Ministerio de Educación Nacional,that identified with the traditionalist view, as well as some of the art critics and their critiques on exhibitions and collections of art, that were being questioned by the new generation. (2) The philosophical reasons did not deviate, not even a bit, from the common allegations: These are all leftist stances that are “compromised” and argued by the anthropologist Gilberto Antolinez (1945), the artists César Rengifo (1948) and Pedro León Castro (1949), and by the historian Mario Briceño Iragorry (1952). (3) The accusations about abstract art were the same used by the Soviet Union, Mexico, and other Latin American countries, especially those with strong indigenous ancestry, as an incomprehensible art and a product of decadent societies. Interestingly, among those “loyal to culture” personalities, referenced by the writer, were Alfredo Boulton and Carlos Raúl Villanueva; the first, the original organizer and patron of the avant-garde abstract group of artists; and the second, the architect of the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas and the one promoting the “integration of the arts” concept, an experiment alluded to by the journalist, in trying to responsibly justify Otero’s use of art as being servient to architecture.