Lasar Segall’s lecture on German Expressionism was not published until 1954, when the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo finally decided to include a portion of the original text in its Literary Supplement. This document was among those that helped to promote the language of Expressionism in Brazil; it also shed light on the intense effort that was involved in refreshing the country’s intellectual life in the 1920s, particularly as regards European art. It is common knowledge that, in those days, Brazil considered itself to be a modernist country. In his lecture, Segall identified “Expressionist” traits in artists such as Marc Chagall, Franz Marc, Paul Klee, Henri Matisse, Henri Rousseau, and Wassily Kandinsky. In Segall’s opinion, the works produced by these artists include “primitive” representational elements that go far beyond the virtuoso techniques demanded by “aesthetic harmony.” He goes on to say that, because it appeared during “humanity’s greatest spiritual crisis”—he was referring to the armed hostilities of the early twentieth century—Expressionism represents the “human aspect of art” that allows artists to express their feelings, their “internal world,” which, in the final analysis, “is everyone’s world.” Expressionism is manifested through an “instinctive visual force,” devoid of any program devised to impose a doctrinaire approach to addressing either form or color.

Lasar Segall (1891–1957) was born in Vilnius, Lithuania, where his family was part of the Jewish community. He enrolled in the School of Applied Arts in Berlin and, in the early years of the century, spent time at the Academy of Fine Arts. In 1912 he travelled to Brazil, where his brothers were already living. The Centro de Ciências e Artes de Campinas (São Paulo) bought one of his paintings: Cabeça de menina russa (1908). He returned to Europe during the First World War. Joining forces with a group of German painters (such as Otto Dix) he co-founded the Dresdner Sezession – Gruppe 1919. After an exhibition of Russian art in Hanover in 1921 he established a relationship with Kandinsky. In 1923 he returned to Brazil. He painted a mural at the Pavilhão de Arte Moderna, a meeting place for artists and intellectuals at the home of the great promoter of the Semana de Arte Moderna of 1922, Mrs. Olivia Guedes Penteado. The mural was reviewed by Mário de Andrade, who identified his “Brazilian phase” (1924–28). Segall took part in SPAM’s Primeira Exposição de Arte Moderno and the Spamolândia project in 1934. Three of his paintings and seven prints were featured in the Entartete Kunst Ausstellungsführer [Exhibition of Degenerate Art] organized by the Nazis in Munich in 1937 to discredit modern art. In the 1940s Segall traveled, painted stage sets, and illustrated books and magazines. His major work, Navio de emigrantes (1939–41), was highly praised by George Grosz.

For more information on this painter’s essays about art in Brazil, see the text “Existe uma arte judaica?” [doc. no. 783319] and the interview “O que é a SPAM, que se inaugurou quinta-feira à noite” [doc. no. 783486].

The noted critic, poet, musicologist, and cultural promoter Mário de Andrade (1893–1945) closely followed Segall’s career in Brazil, writing several articles outlining what he described as the painter’s “visual art biography” during the time he lived in Brazil [doc. no. 783393]. He also introduced the album of drawings of the work Mangue produced by Segall [doc. no. 1111411].

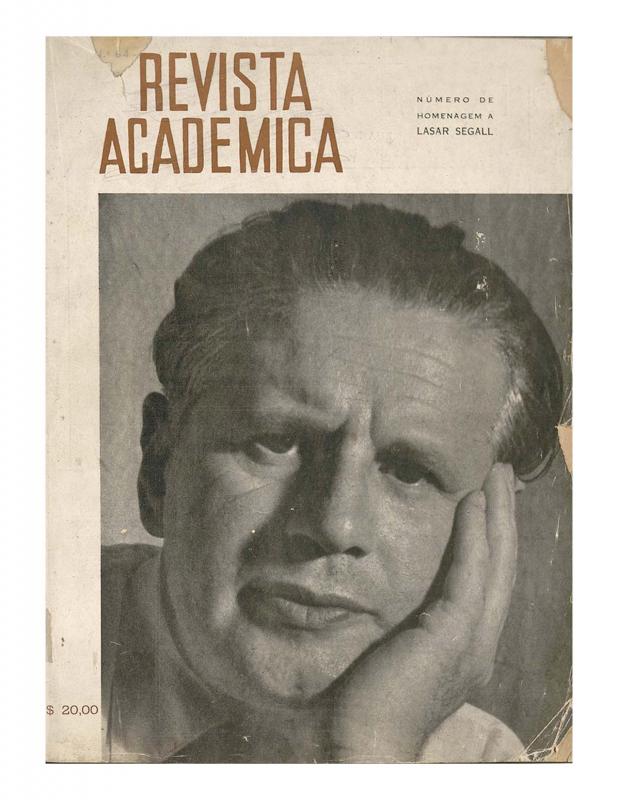

There was also a great deal of interest in the 82 pages devoted to him in the “Revista Acadêmica: número de homenagem a Lasar Segall” [doc. no. 1110322] and a critical essay by Abilio Álvaro Miller, “Um pintor de almas” [doc. no. 1084988].