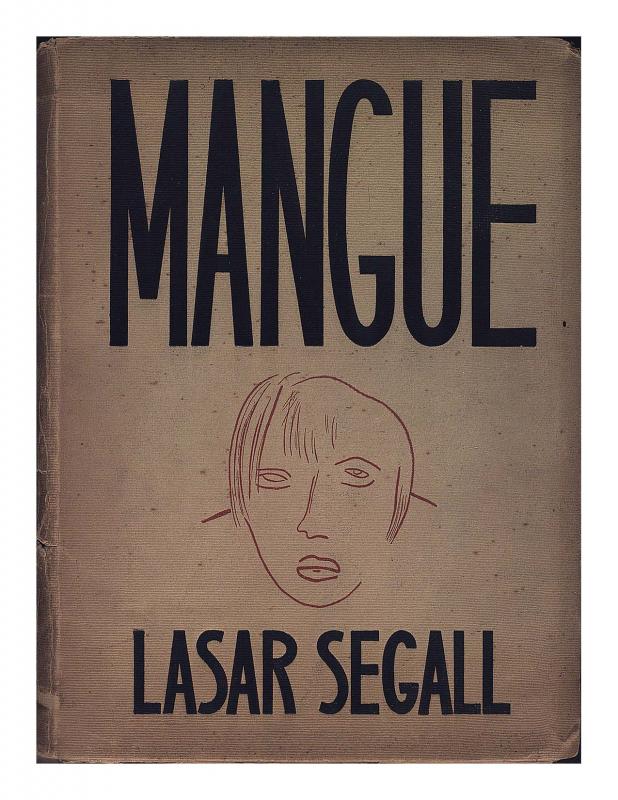

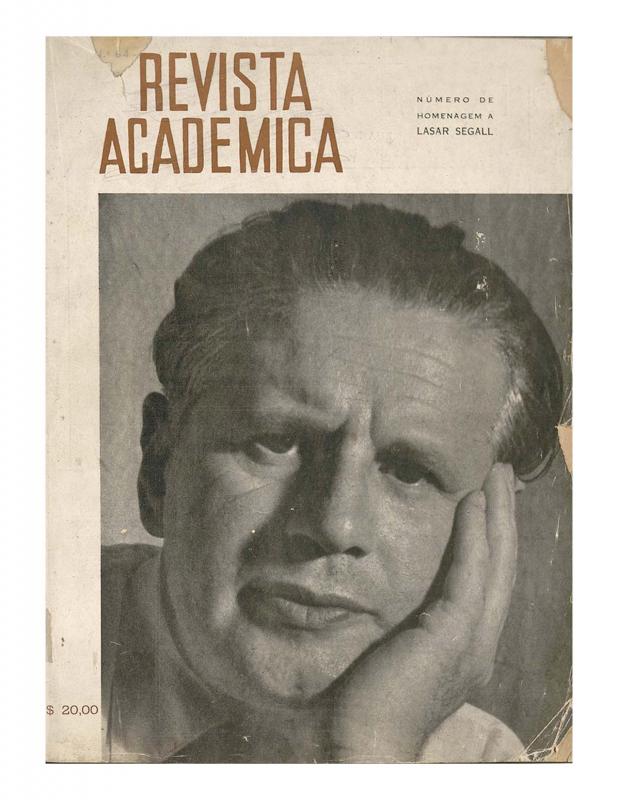

Although this text was originally published in the portfolio of drawings and prints entitled Mangue [Mangrove Swamp] by Lasar Segall [see doc. no. 1110480], the article barely refers to the artist’s works. Its only comment is the hieroglyphic way Segall draws women from the red-light district featuring prostitution in Rio de Janeiro: in the windows, among curtains. He draws them using a “confidential” tone, without the “didacticism” that Mário de Andrade attributes to painting and sculpture. The reproduction of this essay in the Revista Acadêmica (in 1945, as a tribute to Mário de Andrade, in the light of his recent death) is introduced by a note from the editor in which he explains that very few people have had access to this text, perhaps just a handful of bibliophiles. “Do desenho” is one of the “most notable articles written by this writer.” In fact, it was one of the first efforts to conceptualize drawing as an autonomous language of expression. Another version of the text (with no reference to the Segall portfolio) can be found in the book Aspectos das Artes Plásticas no Brasil (1965).

Throughout his life, Mário de Andrade (1893–1945) followed Lasar Segall, as an artist, right from his beginnings. He introduced the catalogue of a 1943 exhibition at the el Museu Nacional de Belas Artes do Rio de Janeiro, which provides what the writer calls an “art biography” of the artist’s time in Brazil.

Lasar Segall (1891?1957) was an artist born in the Jewish community of Vilnius (Lithuania). He studied at the Berlin School of Applied Arts, and, in the early 1900s, he frequented Berlin’s Academy of Fine Arts. In 1912, he travelled to Brazil to join his brothers, who were already living there; the Centro de Ciências e Artes de Campinas (São Paulo) acquired one of his works: Cabeça de menina russa (1908). During World War I, he returned to Europe, where, along with German painters such as Otto Dix, he founded the Dresdner Sezession – Gruppe 1919. Starting with an exhibition of Russian art in Hannover (1921), Segall established ties with Kandinsky; then, in 1923, he returned to Brazil. He painted murals on the walls of the Pavilhão de Arte Moderna, a meeting place for artists and intellectuals and the house of the great promoter of the Semana de Arte Moderna in 1922, Mrs. Olivia Guedes Penteado. This work earned him a review by Mário de Andrade, who deemed this time as Segall’s “Brazilian period” (1924?28). The artist participated in the Primeira Exposição de Arte Moderno, sponsored by the [Sociedade Pró-Arte Moderna] (SPAM) in 1933, as well as in the project Spamolândia (1934). Three of his paintings and seven prints were included in the exhibition Entartete Kunst Ausstellungsführer [Degenerate Art] organized by the Nazis in 1937 to discredit Modern art. During the 1940s, Segall traveled, executed set designs and illustrated books and magazines. His masterpiece, Navio de emigrantes (1939?41), won him praise from George Grosz.

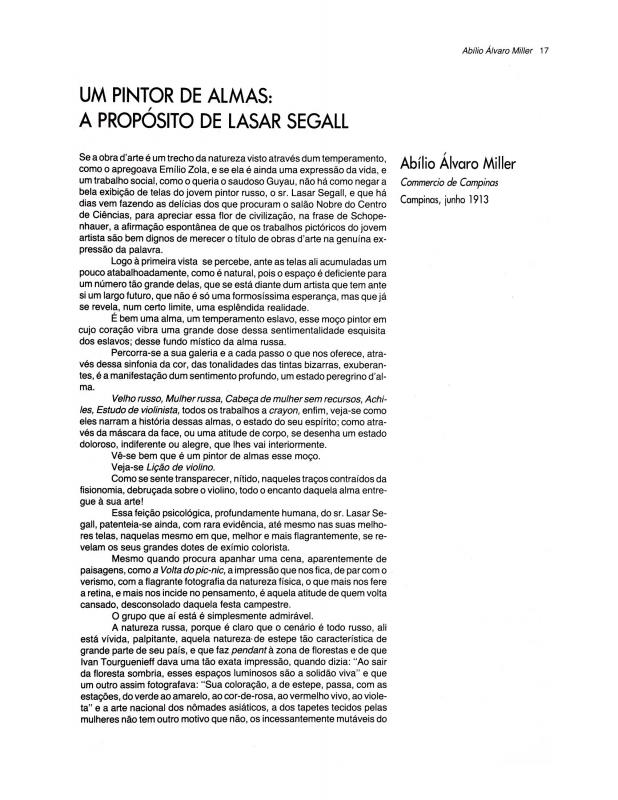

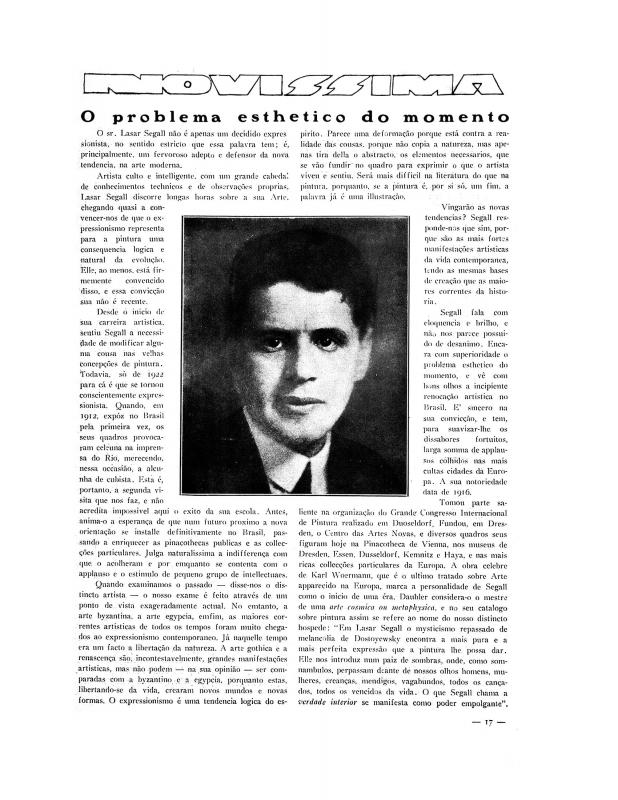

Regarding other articles on Lasar Segall, Abílio Miller wrote what may have been the first criticism of his work in “Um pintor das almas” [doc. no. 1084988] during an exhibition in São Paulo in 1913. Subsequently, the journal Novíssima (1923) published an anonymous article on Segall’s second stay in Brazil and his aesthetics, “O problema esthético do momento” [doc. no. 781161]. In 1944, the Revista Acadêmica dedicated an 82-page issue to this artist, “número de homenagem a Lasar Segall,” including this text [doc. no. 1110322].