Dámaso Ogaz (1924–1990) writes about the painter Hernán Gazmuri (1900–1979), who was his teacher. According to the art historian Antonio Romera (1908–1975), Gazmuri’s work was gradually forgotten in Chile, despite the fact that it was a very particular form of visual art. Gazmuri went to Europe (from 1928 to 1931) to continue his studies. He trained at the Academia de Bellas Artes, where he enrolled in 1919, but was critical of the teaching he received there because students were not encouraged to explore contemporary art trends in the first decade of the twentieth century. As a student leader, he lobbied for the establishment of a system of grants to support study tours to Europe. His concerns in this area led him to join the Grupo Montparnasse in order to challenge the academism that dominated Chilean painting at the time, both in art instruction and in the kind of works that were applauded by the critics. He returned to Chile in 1934 and taught classes on Cubism and abstraction at the Escuela de Bellas Artes de la Universidad de Chile, earning the contempt of the painter Marco Bontà (1899–1974), who criticized him publicly in a column published in the newspaper El Mercurio, saying that teaching of that kind was feckless and encouraged imitating what foreign artists were doing. This line of criticism led to the cancellation of those classes. Gazmuri nonetheless persevered in his quest to teach modern art and, in 1935, founded the Academia Libre de Artes Plásticas. [For more information, see the following in the ICAA Digital Archive “La pintura de Hernán Gazmuri” (doc. no. 750435) by Antonio Romera.]

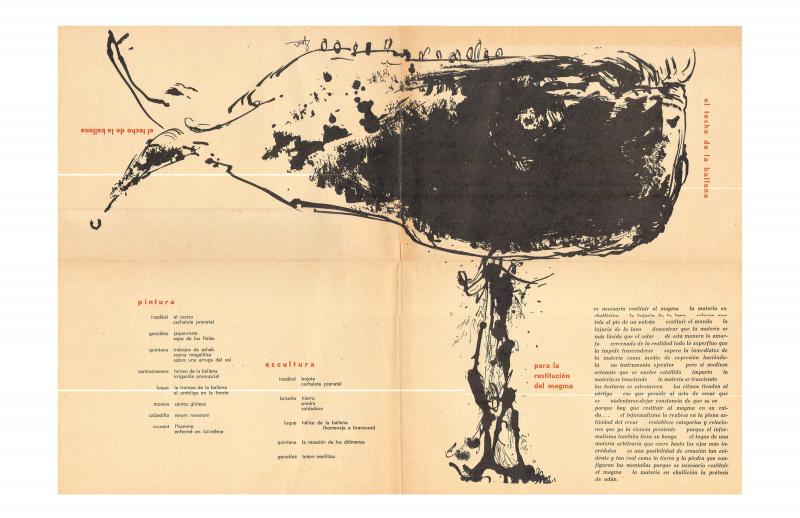

Dámaso Ogaz—Víctor Manuel Sánchez Ogaz—was born in Chile but emigrated in 1961. Before he left the country, he wrote a column about art for the magazine En viaje published by the Empresa de los Ferrocarriles del Estado, the State Railway Company, which appeared in a section called “In the Exhibition Rooms.” He went to Venezuela first, intending to promote the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Americano de Trujillo, which closed the following year. He was a member of El Techo de la Ballena, an irreverent art and literary group that questioned the return to democracy in the wake of the Pérez Jiménez dictatorship and published his poems and drawings on the avant-garde collective’s posters and publications. He went to Paris in 1963, then settled permanently in Caracas in 1967. In the early 1970s he created the experimental magazines La Pata de Palo and Cisoria Arte; he also produced works of mail art. The Uruguayan poet and artist Clemente Padín (b. 1939), who lives in São Paulo, recalled that he was influenced by Ogaz’s works and his impulsive anti-establishment attitude. [On the subject of the Caracas group, see “Rayado sobre el Techo de la Ballena: letras, humor, pintura” (doc. no. 1142155).]