In his essay “La pintura de Hernán Gazmuri” (1959), the historian and art critic Antonio Romera (1908–75) discusses the work of the painter Hernán Gazmuri (1900–79). Some years earlier, in his book Historia de la pintura chilena (History of Chilean Painting, 1951), he explained that Gazmuri kept his distance from the art circuit, a move that, to a certain extent shut him off from the art world. He nonetheless speaks very highly of Gazmuri’s work, referring, on several occasions, to Homenaje a Andrés Lhote (1932), one of his best-known paintings. This “homage” was an expression of gratitude to the French painter who was his teacher while he was in Paris, where Gazmuri came to study, at his own expense, in 1928 and stayed until 1931. At an earlier time—influenced by French painting—Gazmuri was a member of the Grupo Montparnasse, the group that challenged the academism in Chilean painting that set the standards for the kind of works that were considered worthy and determined how art was taught.

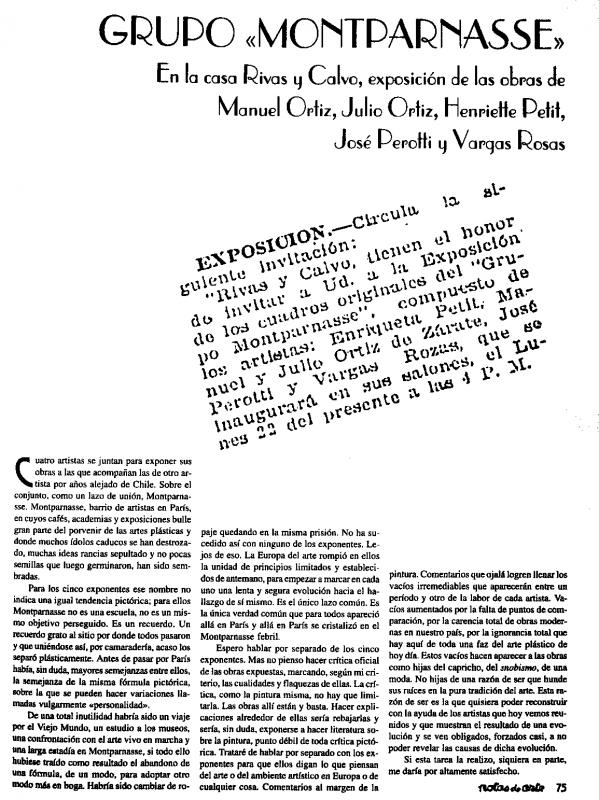

The group made its first public appearance in 1923 at an exhibition of paintings at the Casa de Remates Rivas y Calvo in Santiago. Participants on that occasion were the painters Henriette Petit (1894–1983); José Perotti (1898–1956), who was also a sculptor; Julio Ortiz de Zárate (1885–1946), who was considered part of the Generación del 13; and Luis Vargas Rosas (1897–1977), the founder. Two years later, at another exhibition presented at the same venue, those mentioned above were joined by the painters Manuel Ortiz de Zárate (188–71946), Julio Ortiz de Zárate’s brother; Camilo Mori (1896–1973); Isaías Cabezón (1891–1963); Augusto Eguiluz (1893–1969); Romano de Dominicis; Sara Malvar (1894–1970); and Gazmuri. They enjoyed the approval and support of the art critic Jean Emar (1893–1964), the pseudonym adopted by Álvaro Yañez Bianchi, who wrote for the newspaper La Nación. Despite the hiatus between the two exhibitions, the clash between an “academic” style of painting and a more “innovative” version that challenged art’s formal parameters persisted for many years. The 1928 salon, another important occasion in that debate, was seen as a watershed event by the art historians Gaspar Galaz (b. 1941) and Milán Ivelic (b. 1935). Gazmuri was one of many artists at that salon, several of whom were accused of wanting to “‘deform’ representation” and exploit painting salons for those purposes. It should be noted here how those early discussions helped to start the debate about what was considered painting and representation and, thus, the avenues open to artists. [To learn more about the Generación del 13, see the following in the ICAA Digital Archive: “Apuntes para un estudio de la Generación del ‘13” (doc. no. 773707) by Ricardo Bindis; and the article “Grupo "Montparnasse. En la casa Rivas y Calvo, exposición de las obras de Manuel Ortíz, Julio Ortíz, Henriette Petit, José Perotti y Vargas Rosas” (doc. no. 750202) written by Jean Emar; on the subject of Gazmuri, see “Texto introductorio Exposición Sala Libertad” (doc. no. 750426)].