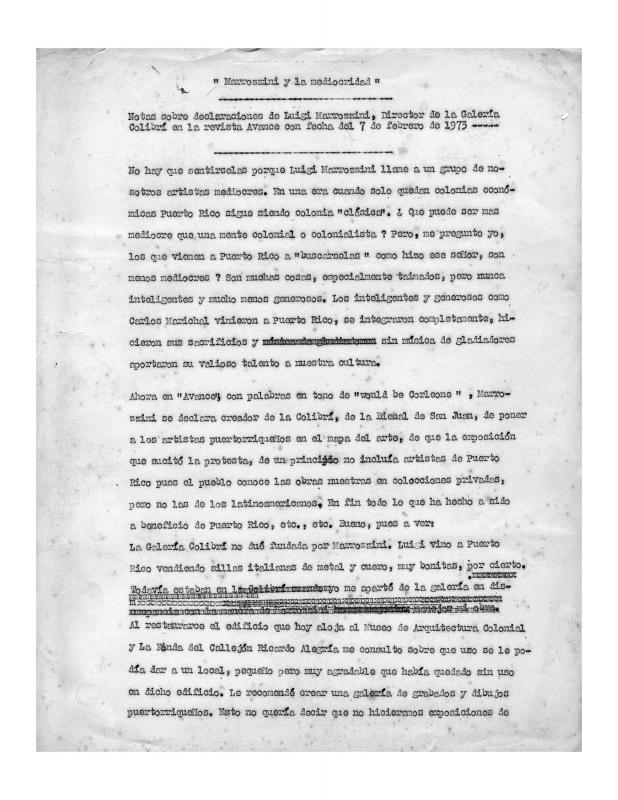

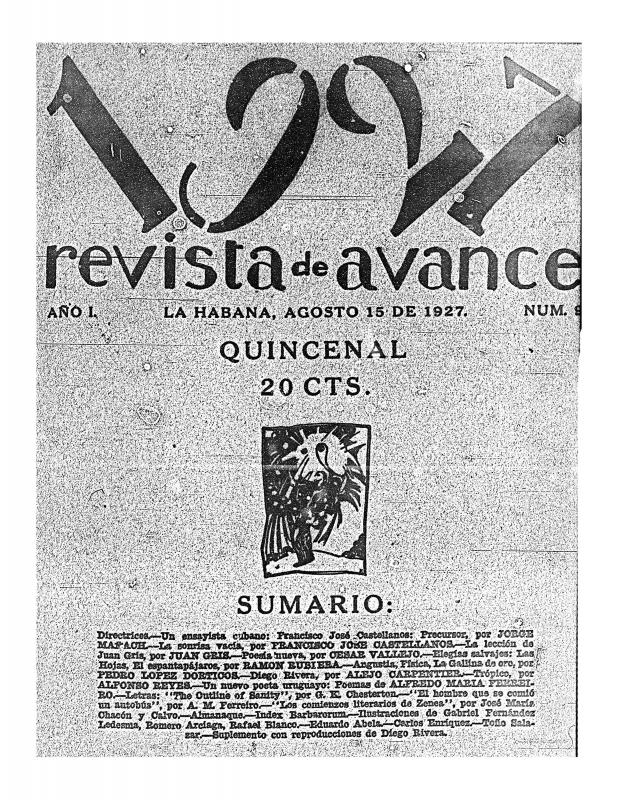

The Revista de avance, which promoted this exhibition and its development of a “new art” from its inception, was also involved in the process of selecting the artists and the work. Many of the discussions generated in avance were related to the ethical and aesthetic issues on which artists and writers were focusing at the time. These contributed to encouraging the intellectual and artistic milieu in which the characteristics of avant-garde art in Cuba could be considered. Both the pages of Revista de avance and the presentation of 1927: Exposición de Arte Nuevo reflected an eagerness to break with academic art practices and the desire to express the nature and sensibility of a certain time and worldview. The “incident” related to works by Carlos Enríquez, categorizing them as “exaggerated realism,” is evidence of the strong reactions stirred up in the Cuban viewing public by some of the work in the show. In general, the exhibition was welcomed by middle-class professionals; however, Carlos Enríquez’s nudes were alarming to the conservative tastes of some of the viewers. One of the best-known painters of the Cuban avant-garde, Carlos Enríquez came from an upper-class family and had studied business and art in Pennsylvania, where he met the woman he would marry, the artist Alice Neel. Back in Havana, he took up with the movement of young intellectuals and artists who contributed to avance and had several individual exhibitions. In 1927, he headed off to New York, where he stayed for a time before moving on to Paris. It was in Paris where he joined a small group of Cubans who, like himself, would find the inspiration to create a personal vision and style in Cuban themes. His most famous work, El Rapto de la Mulata, brings mythical characters together with criollo culture, represented by the mulatto and the peasant. This work was said to have been inspired by the classical myth of the “Rape of the Sabine Women,” which had been interpreted by various artists such as Nicolas Poussin, Jacques-Louis David, and Pablo Picasso in different periods. [For other essays and texts published in Revista de avance, see the following in the ICAA digital archive: “Índice del Tomo I (Números 1 al 12 inclusive)” (anonymous) (doc. no. 1300106); by Martí Casanovas “Almanaque” (doc. no. 1299709), “Almanaque: Exposición Gattorno” (doc. no. 1298711), “El capitalismo y la inteligencia” (doc. no. 1299384), “Nuevos Rumbos: La exposición de ‘1927’” (doc. no. 1280155), and “Pierre Flouquet” (doc. no. 1299881); “[El arte nuestro debe ser instintiva o intuitivamente americano...],” by Víctor Andrés Belaúnde (doc. no. 832310); “[Basta con que revele una honda...],” by Carlos Préndez Saldías (doc. no. 832258); “Causerie sobre el Salón de Bellas Artes,” by Adia M. Yunkers (doc. no. 1298799); “[Creo que el artista americano...],” by Ildefonso Pereda Valdés (doc. no. 832328); “Dibujos escolares” (anonymous) (doc. no. 1299805); “Diego Rivera,” by Alejo Carpentier (doc. no. 1299962); “Eduardo Abela: pintor cubano,” by Adolfo Zamora (doc. no. 1280283); “El futuro artista,” by Eduardo Abela (doc. no. 1299789); by Juan Marinello “El insoluble problema del intelectual” (doc. no. 1299897), and “El momento” (doc. no. 1125671); “El prejuicio en el ritmo intelectual de las épocas,” by Francisco Ichaso (doc. no. 1299741); “El problema internacional de Centro América y Cuba,” by Fernando de los Ríos (doc. no. 1300090); “La cuestión del negro” (anonymous) (doc. no. 1280299); “La lección de Juan Gris,” by Juan Gris (doc. no. 1299946); “Marrozzini y la mediocridad: notas sobre declaraciones de Luigi Marrozzini,” by Lorenzo Homar (doc. no. 861634); “Martí: Poeta Nuevo,” by Raúl Roa García (doc. no. 1300003); “Nacionalismo y Costumbrismo,” by Severo García Pérez (doc. no. 1300058); “Nacionalismos en América,” by Eugenio d’Ors (doc. no. 1299757); “Nota de los 5—2,” by Jorge Mañach et al. (doc. no. 1299930); “Programa de criolledad,” by Félix Lizaso (doc. no. 1125414); and “Vértice del gusto nuevo,” by Jorge Mañach (doc. no. 832383)].