In his (esoteric) thinking, Joaquín Torres García (1874–1949) explicitly rejects social and political passions that, in his view, lead to wars and other conflicts. His search for the Essential Man ensues at the margins of partisanism (“our divorce from the historical is absolute […]”). Nonetheless, he takes the opportunity to make statements against the process of modernity and to call Western civilization “decadent.” He does not deny animist ideas that see things as endowed with spirits, which in turn take shape in signs. He even mentions pantheism as universal concept implicit to constructivist doctrine (the monism of the ONE: all things are the same insofar as parts of the whole). Joaquín Torres García declares his absolute skepticism about human evolution. If constructivism is outside History and the circumstances that define the social features of a given period, it must also be outside the idea of evolution enmeshed in modern thought. The artist also insinuates an underlying belief in categories for human beings based on date of birth—something that condemns them for life to a certain place in the allegory of the pyramid. He recommends resignation in the face of a fate that justifies the paralysis of social movements perhaps because doomed to fail. Torres García also deems impossible any “moral change” that might be brought on by, say, embracing the constructivist doctrine in an intellectual climate like the one in Montevideo at the time. With that, he also expresses his disdain for a milieu that was at best indifferent, and perhaps even hostile, to his aesthetic formulations.

In closing, the artist states that the Asociación de Arte Constructivo will remain open as a research center for those who want to explore his philosophy, but not as a breeding ground of a movement that he declares nonexistent and impossible to form. Two years later, in his 500th lecture, the artist returned to his bold prior way of thinking after making peace with significant resignations; he attempted to adapt his universalist theory to the historicism of local expectations. Had he not adjusted his thinking in that way, the Taller Torres García (TTG), founded four years after this manifesto was published, would never have been established.

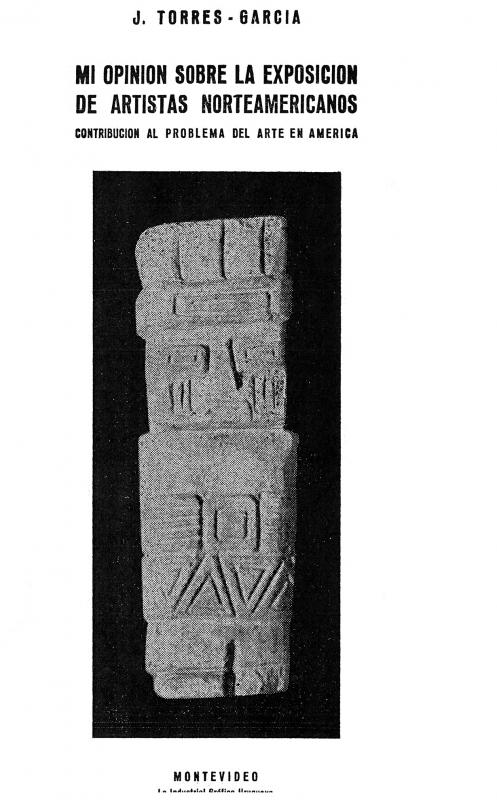

[For further reading, see in the ICAA digital archive the following texts: Guido Castillo’s “Manifiesto 2, sobre el Salón de Artes Plásticas” (doc. no. 1250837); and by Joaquín Torres García “Con respecto a una futura creación literaria” (doc. no. 730292), “Lección 132. El hombre americano y el arte de América” (doc. no. 832022), “Mi opinión sobre la exposición de artistas norteamericanos: contribución” (doc. no. 833512), “Nuestro problema de arte en América: lección VI del ciclo de conferencias dictado en la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de Montevideo” (doc. no. 731106), “Introducción [en] Universalismo Constructivo” (doc. no. 1242032), “Sentido de lo moderno [en Universalismo Constructivo]” (doc. no. 1242015), and “Bases y fundamentos del arte constructivo” (doc. no. 1242058)].