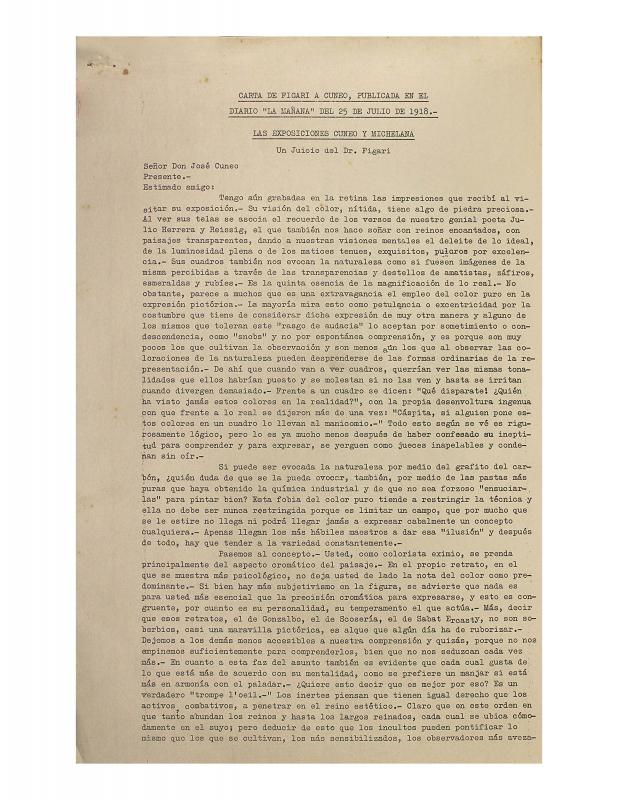

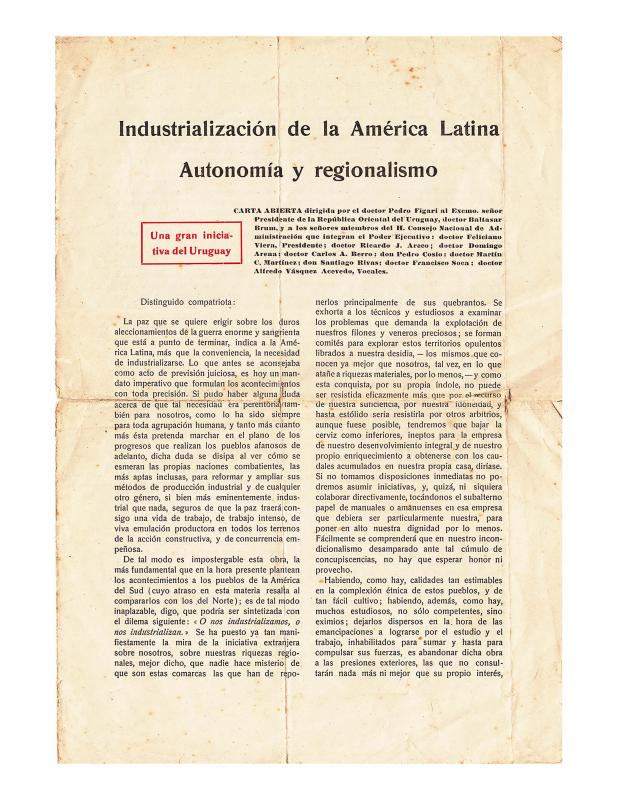

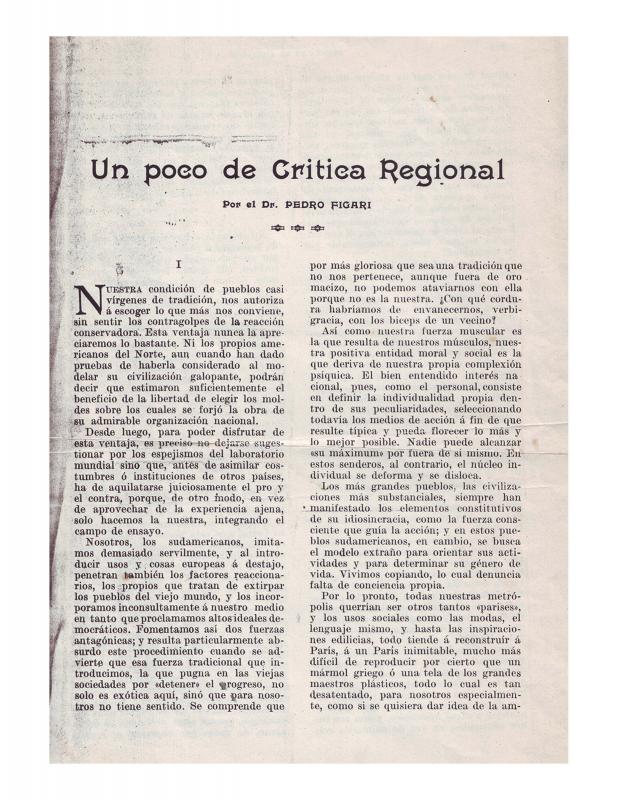

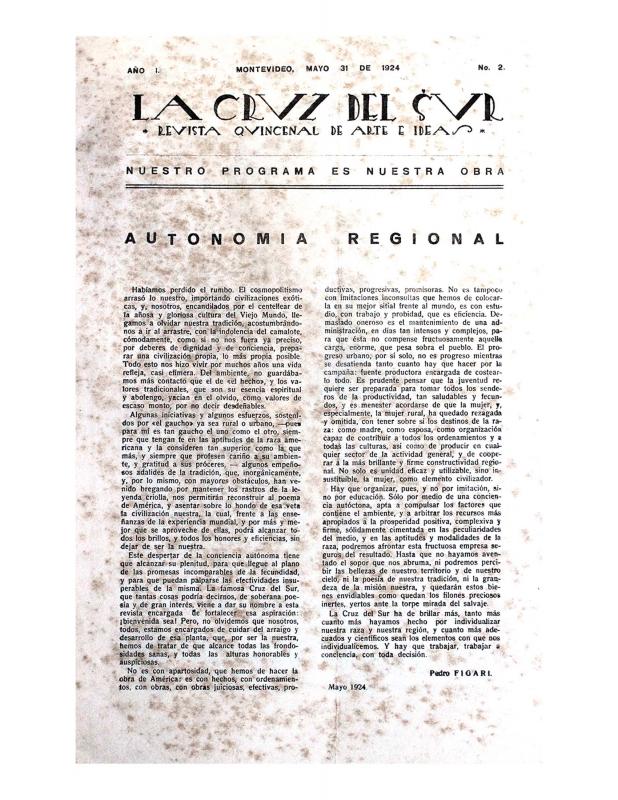

In 1951 Ángel Rama (1926–83) published “La aventura intelectual de Figari,” the first serious essay written in Uruguay about the pictorial, literary, and philosophical work of Pedro Figari (1861–1938). Five years later, Arturo Ardao (1912–2003) devoted a chapter of his book Filosofía en el Uruguay en el siglo XX to the same subject, but in this case focusing exclusively on Figari the philosopher. The article by the Uruguayan historian, philosopher, and theologist Alberto Methol Ferré (1929–2009), published in 1960—while providing just a hint of a more ambitious work about the “900 Generation”—reports on the third installment in the intellectual evolution of Figari’s philosophical thinking, which happened almost fifty years after he published his essay “Arte, Estética, Ideal”. When he wrote this brief article, Methol Ferré had just published his book La crisis del Uruguay y el Imperio Británico (1959) and was an occasional contributor to Marcha, the weekly newspaper. In this article he equates the aesthetic idea proposed by Vaz Ferreira (1872–1958), who compared the concept of “beauty” to the concepts of “utility and necessity,” with the one endorsed by José Enrique Rodó (1871–1917), whose view of “aesthetics” had nothing to do with material necessities, thus creating a problem related to the mystery of “transcendence.” Both men had been educated at a positivist university. Methol Ferré was the first to point out that Figari disagreed with his two famous colleagues by considering “aesthetics” to be merely an aspect of human ingenuity whose function was to improve the species and satisfy certain vital necessities. That vitalism (or biologism) represents a counterattack on the aesthetic idealism that other distinguished exponents of the so-called Generación del Novecientos maintained intact, despite diluting it to some extent in empirical and scientific theses in the late nineteenth century. At the end of the article, the author refers to a remarkable aspect of Figari’s counterpoint that fluctuates somewhere between his painting and his philosophy; while Figari refers to the vagueness of what he calls an “idealizing aesthetic,” he also compares it to a productive, rational aesthetic rooted in practice, which he calls an “ideating aesthetic.” He thus produced an evocative kind of painting based on amnesiac fantasies that was closer to idealization that ideation. Pedro Figari was active in several different cultural areas, as a philosopher, journalist, educator, lawyer, politician, and artist. He worked for the development of a universal humanism that included, and was based on, an empathetic knowledge of the cultural heritage of the region that was expressed in the local traditions, nature, and society. [As complementary reading see, in the ICAA digital archive, the following articles by the Uruguayan polymath: “Las exposiciones Cuneo y Michelena [Un juicio de Pedro Figari]” (doc. no. 1233819); “Industrialización de la América Latina, Autonomía y Regionalismo: Carta abierta dirigida por el Dr. Pedro Figari al Excmo. señor Presidente de la República Oriental del Uruguay” (doc. no. 1181222); “Un poco de crítica regional” (doc. no. 1258164); “América Autónoma: no basta instruir, hay que enseñar a trabajar” (doc. no. 795325); “Arte, técnica, crítica. Conferencia bajo el patrocinio de la Asociación Politécnica del Uruguay” (doc. no. 1263840); “Autonomía Regional” (doc. no. 1254337); and “Una carta de Pedro Figari” (doc. no. 1197040)].