In his letter, Pedro Figari (1861–1938) restated the demands he had been making in his cultural discourse from 1900 to 1917, calling for a uniquely South American “culture of productivity” inspired by a regionally-flavored pedagogical and heuristic approach. At the time of writing, in 1919, it had been barely two years since Figari had been obliged to put an end to his pioneering stint as head of the Escuela de Industrias (or “Escuela de Artes” as he called it) in the capital city of Montevideo. In this letter, however, his cultural discourse veered into political territory by addressing a message to the Uruguayan government and by using arguments referring to the political history of the nations that squared off against each other on the battlefields of the First World War. By naming Germany as a model of “diligence” (an individual or country with a tendency to generate their own culture of productivity) Figari was referring to the nationalist tone adopted by the emerging industrial Germany (developed through the Werkbund, the German Association of Craftsmen); he was also, to some extent, challenging the anti-German stance held by the Uruguayan government during the First World War. His statement also, however, included an anti-colonial message: he was suspicious of the covetous interest that powerful nations were already showing in South America’s raw materials, and said the continent should assert its economic and cultural autonomy based on new public policies designed to promote small- and medium-sized industries that could contribute to the quantitative and qualitative rise of the urban and rural classes. This letter included some of Figari’s key ideas. In the first place, his definition of art as “ingenuity in action” that led him to see art and industry as complementary elements. In the second place, his view of regional industries as a form of resistance against the forces of neo-colonialism (his main concern was: “either we become industrialized or others will do it for us”); and, in the third place, his understanding that “industrialization” was more of an active cultural principle applied to individuals and society as a whole than an advanced technical update of the country’s production systems.

It should be noted that though this letter includes the term “Pan-Americanism,” its meaning here is not the same as the meaning implied later on in the United States’ foreign policy after the 1930s. The neo-colonial threat of the Monroe Doctrine (1823) and its corollary in Theodore Roosevelt still lingered in 1919, which did not prevent Figari from referring to the production methods used by industry in the United States as an example to make his point. Figari’s version of Pan-Americanism was essentially a reference to the need for internal cooperation between Latin American countries; the term has an explicit ethnic subtext because—as José Vasconcellos did in México (La raza cósmica, 1924)—Figari spoke of an “American race” of “people with identical origins, needs, and aspirations.” In fact, the Uruguayan painter and thinker used the terms “Latin America,” “South America,” and “Virgin America” as synonyms. It was to some extent a political-cultural approach to the racial aspect of the continent that can also be seen in Figari’s painting.

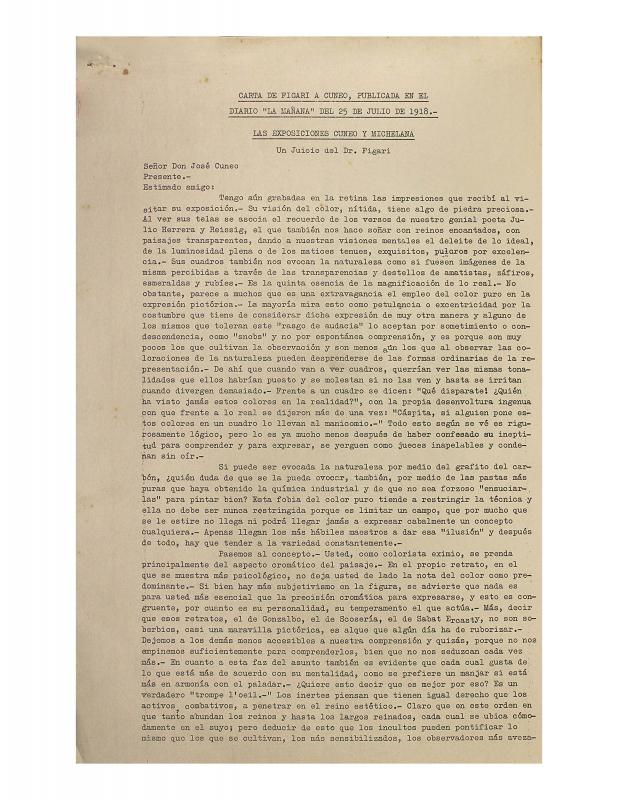

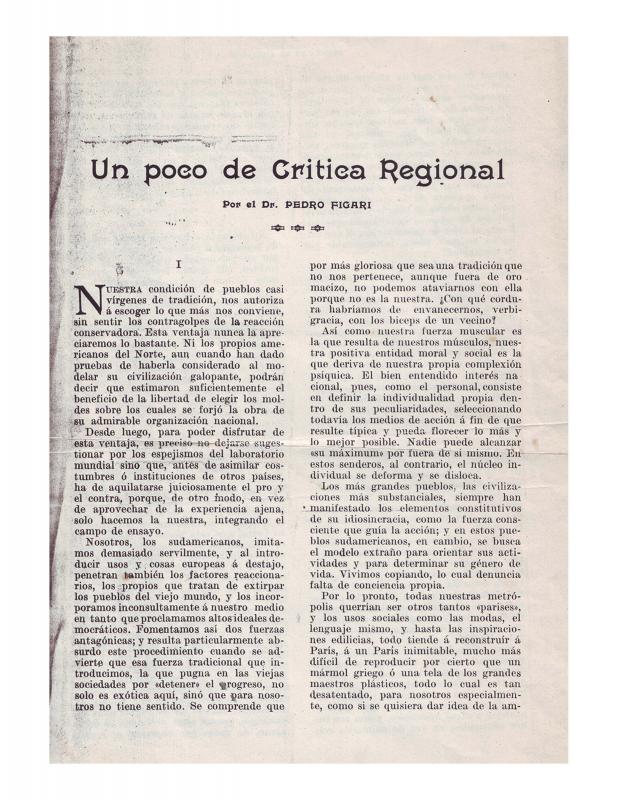

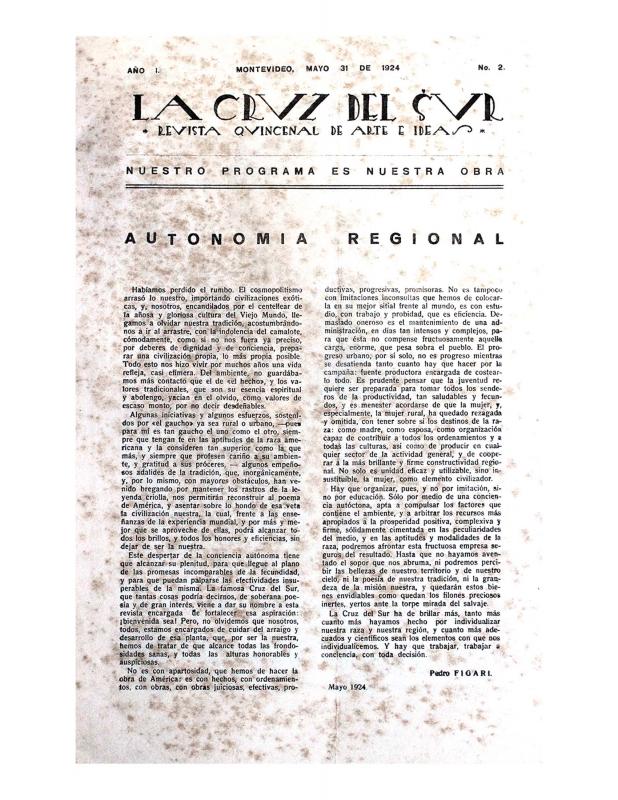

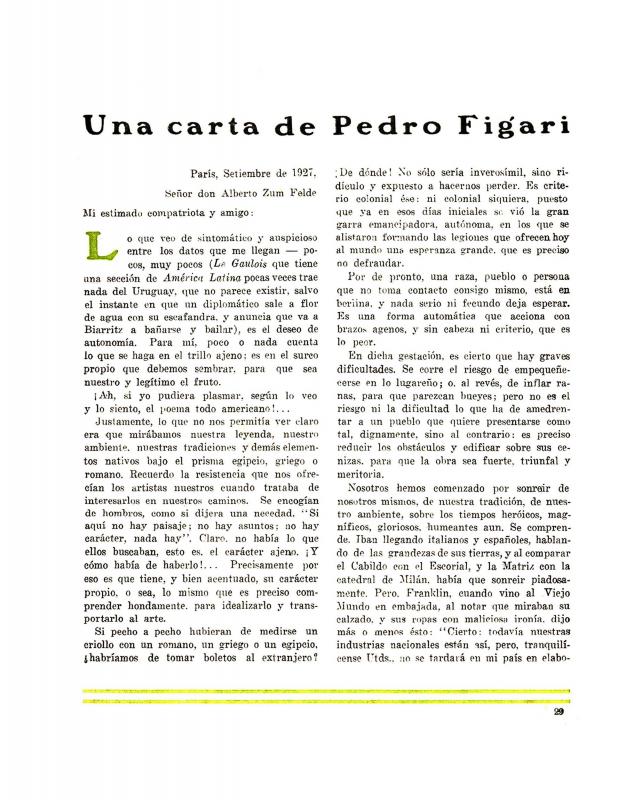

[As complementary reading, see the following texts by Pedro Figari in the ICAA digital archive: “Las exposiciones Cuneo y Michelena [Un juicio de Pedro Figari]” (doc. no. 1233819); “Un poco de crítica regional” (doc. no. 1258164); “América Autónoma: no basta instruir, hay que enseñar a trabajar” (doc. no. 795325); “Arte, técnica, crítica. Conferencia bajo el patrocinio de la Asociación Politécnica del Uruguay” (doc. no. 1263840); “Autonomía Regional” (doc. no. 1254337); and “Una carta de Pedro Figari” (doc. no. 1197040)].