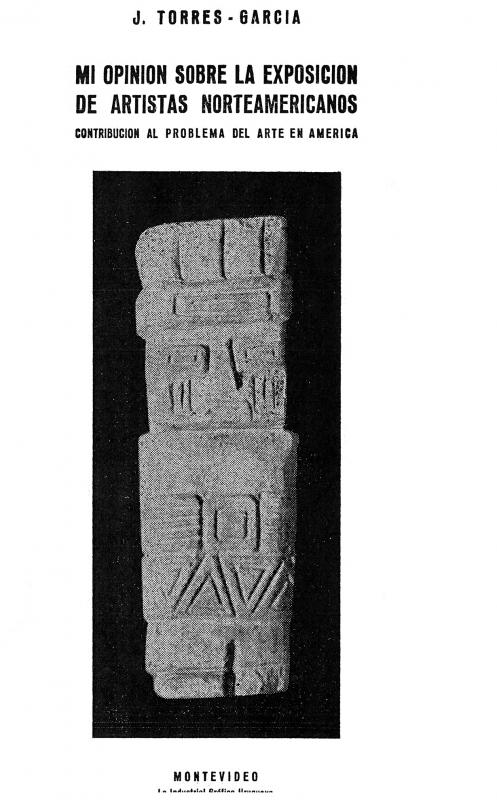

It is significant that Joaquín Torres García began this conference by determining that the functional character of an artist is his method. [The artist thereby] attempts to clarify and ascertain the representation of the world through functional characteristics in a certain order, in a certain proportion, and with a certain rhythm constituting “a structure,” which is a symbol of a universal unit. The closeness of Torres García to Ozenfant [Amèdèe] and Charles Edouard Jeanneret [later known as Le Corbusier; both founders of Purism] in Paris, could have brought about such an analogy on the “functional processes” between such disparate fields as those of modern architecture and abstract art. The organic geometry, which characterized the work of Torres García, would be the embodiment of some aspects of the functionalism of visual arts elements at the service of what is called transcendental order, the “function of visual arts elements that are determined in their relation of exact equivalences.” On the other hand, the abstract aspect (the referent signs of Constructivism) would be the “spiritual” dimension marking its history, that is “it being current or being of today,” while the autonomy of the object/sign would be its specific dimension, attributed by the concept of “timelessness” (eternal) universal in aesthetics and moral relevance. Such is the distinction, and at the same time the relation, that Joaquín Torres García established between the abstract and the concrete condition of modern art and his very particular perspective on Constructivist art. This way, by defining his “way of creating” art, the Uruguayan master emphasized the possibility that he himself had an anonymous character that was not due to lack of individuality but instead for his attachment to the “universal rules” that remove the ideas of genius, as well as of protagonist individualism. “No more geniuses on earth!” he wrote. In summary, to “dehumanize” art meant rejecting the molds that historically determined what was considered “the human, the classic, and the romantic” perspective. Such an affirmation must be seen through the perspective of Torres García and the long struggle waged within his art work between what he considered to be his classic and romantic sides as demonstrated by his letters to Rafael Barradas. He tried to resolve a dispute or argument by reaching an agreement with both sides, although minimizing the latter, which was at the core of his Constructivist doctrine. In a sense, this assertion does not lessen his affirmation that both “the romantic” as well as “the poetic” are meant to be lived but not painted. The background of this issue comes from the book La deshumanización del arte (1925), written by the philosopher and essayist José Ortega y Gasset, which marked the era when both Rafael Barradas, as well as Joaquín Torres García, were living in Spain. [For additional reading, please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following texts written Joaquín Torres García: “Con respecto a una futura creación literaria” (doc. no. 730292), “Lección 132. El hombre americano y el arte de América” (doc. no. 832022), “Mi opinión sobre la exposición de artistas norteamericanos: contribución” (doc. no. 833512), “Nuestro problema de arte en América: lección VI del ciclo de conferencias dictado en la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de Montevideo” (doc. no. 731106), “Introducción [en] Universalismo Constructivo” (doc. no. 1242032), “Sentido de lo moderno [en Universalismo Constructivo]” (doc. no. 1242015), “Bases y fundamentos del arte constructivo” (doc. no. 1242058), and “Manifiesto 2, Constructivo 100%” (doc. no. 1250878)].