In the 1920s Joaquín Torres García (1874–1949) left Catalonia to spend almost two years in New York. He had become disappointed with Catalonian “noucentisme” and was now looking for a form of art that suited him and that was more compatible with the contemporary world. This quest had been expressed as a spirit of renewal that could be seen in his work in Barcelona as far back as 1917. The artist, lecturer, and art patron Katherine Dreier (1872–1952) included some of JTG’s constructive paintings and wooden pieces in the collection of twentieth-century avant-garde art funded by Albert Eugene Gallatin that was exhibited at New York University and then became part of the permanent collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. After that, the Sidney Janis gallery and Rose Fried’s Pinacotheca organized solo shows of his works at important museums such as MoMA and the Solomon R. Guggenheim in New York, among others. In the 1950s the worldwide expansion of North American art encouraged by Clement Greenberg’s critical discourse—that was closely linked to the hegemonic policy of the U.S. Department of State during the Cold War—helped to promote the pragmatic approach of the so-called “New York School.” It was therefore not interested in acknowledging the symbolic sources embraced by contemporary artists such as Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. These artists were exploring art that was steeped in “universal” values that used primitive art forms that could be compared to JTG’s pictograms. The Uruguayan artist experimented with a range of different, sometimes opposite, styles and forms, all of which have contributed to his status as a contemporary maestro, albeit one who did not necessarily agree with the inherent values of modernity, and who broke with the paradigms that were adopted by avant-garde artists after the Second World War. In the author’s opinion, both the history of traditional art and the world’s great art institutions have praised JTG’s work as a painter and a teacher over the course of his career. And yet they have refused to recognize the Uruguayan artist’s importance as a point of departure of “something” (that is hard to define) in the history of universal art.

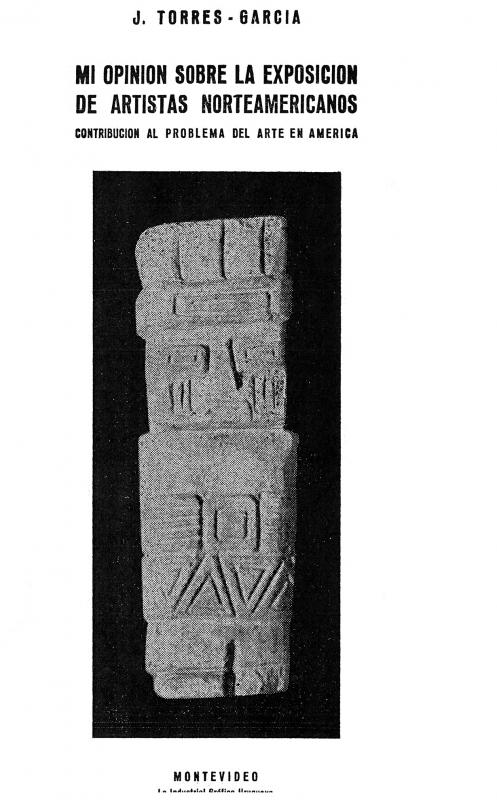

[As complementary reading see, in the ICAA digital archive, the following articles written by Joaquín Torres García: “Con respecto a una futura creación literaria” (doc. no. 730292); “Lección 132. El hombre americano y el arte de América” (doc. no. 832022); “Mi opinión sobre la exposición de artistas norteamericanos: contribución” (doc. no. 833512); “Nuestro problema de arte en América: lección VI del ciclo de conferencias dictado en la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de Montevideo” (doc. no. 731106); “Introducción [en] Universalismo Constructivo” (doc. no. 1242032); “Sentido de lo moderno [en Universalismo Constructivo]” (doc. no. 1242015); “Bases y fundamentos del arte constructivo” (doc. no. 1242058); and “Manifiesto 2, Constructivo 100%” (doc. no. 1250878)].