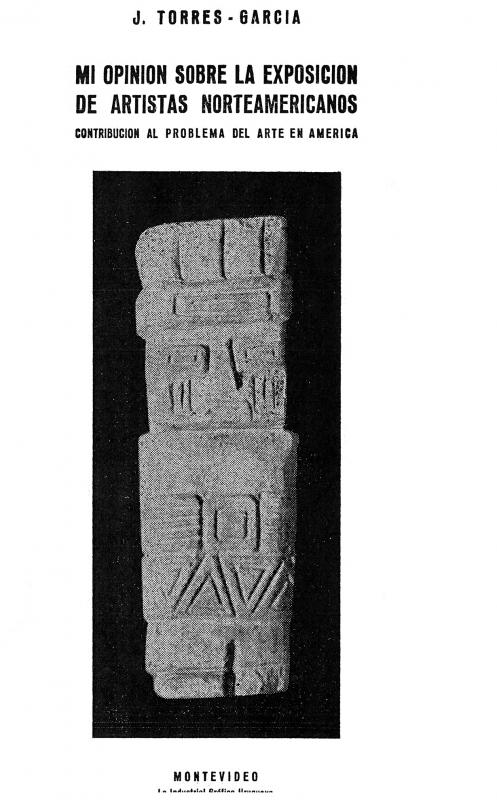

The notion that “our north is the south” was a strategic political statement insofar as it entailed a criticism of the hegemony of Eurocentric culture and a valorization of the margins in a power system that spanned the planet. This “lesson” contains the first version of the inverted map of South America, a symbol to which other artists would later return. Argentinean artist Luis Felipe Noé, for instance, made reference to the map in the exhibition El arte de América Latina es la Revolución, held in Chile in 1972, for which he worked with picket signs and issued a manifesto that asserted revolution as the “true image” of Latin America. Although JTG always held his universal conception of man over any one ethnocentric vision or political affiliation, in this lesson-manifesto he demonstrates the political dimension of culture in the widest sense of the term, expanding it until it becomes an instrument of the Constructivist doctrine. Some of his statements echo Uruguayan painter Pedro Figari who, in the early twentieth century, expressed his disdain for imported trinkets and upheld the need to filter “the foreign” instead of embracing it wholesale, and adapting it to local culture. For JTG, the key lies in being universal from the position of the local. That means discarding both the past, because inadequate in Uruguay, and the future, because uncertain, to take root instead in a “present to be built.” This “radical presentism” is reminiscent of texts the artist published in the magazine Un enemic del poble (1916–17) while in Barcelona, specifically his manifesto for young people. He recommends that the artists of Montevideo visit the port and explore modern urban settings with an eye to “forms rather than things” since “the romantic age of the picturesque is behind us to give way to this golden age of the form.” Four years earlier, JTG had embraced this concept of the visual horizon of modernity and the existence of a presumed citizen’s identity of the “present,” one lacking in a substantial local tradition to be grappled with in art. It was at that point that he wrote the book Metafísica de la Prehistoria Indoamericana; he believed he had found the philosophical basis for his Constructivist art in an American art grounded in a regional tradition tied to the (universal) great tradition of abstract man. [For further reading, see the following texts by Joaquín Torres García in the ICAA digital archive: “Con respecto a una futura creación literaria” (doc. no. 730292); “Lección 132. El hombre americano y el arte de América” (doc. no. 832022); “Mi opinión sobre la exposición de artistas norteamericanos: contribución” (doc. no. 833512); “Nuestro problema de arte en América: lección VI del ciclo de conferencias dictado en la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de Montevideo” (doc. no. 731106); “Introducción [en] Universalismo Constructivo” (doc. no. 1242032); “Sentido de lo moderno [en Universalismo Constructivo]” (doc. no. 1242015); “Bases y fundamentos del arte constructivo” (doc. no. 1242058); and “Manifiesto 2, Constructivo 100%” (doc. no. 1250878)].