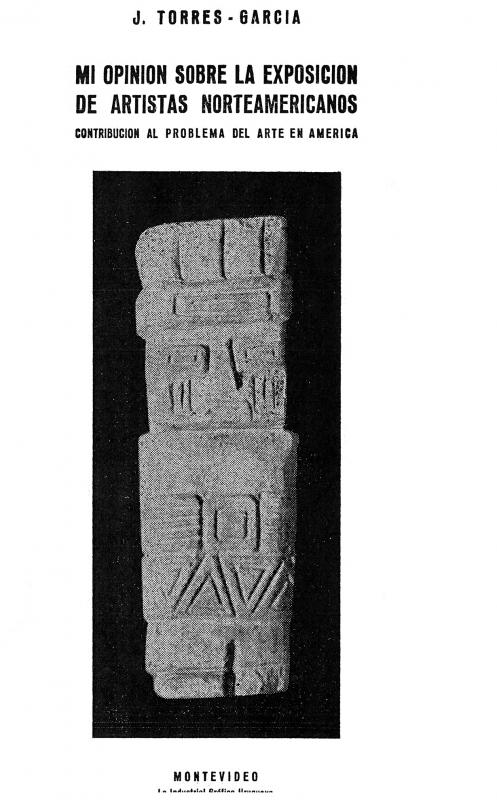

The consideration of “painting” as something that was linked to art yet at the same time is independent of art allowed Joaquin Torres Garcia to safeguard the latter of every individualistic romantic ingredient. His purpose was for art to be governed by the idea of “structure” and “universal values,” leaving creative freedom of the experimental and temperamental characteristics in the hands of painting. He states that “painting is the individual and art is mankind”). Torres García regarded the problem of painting as strictly related to the visual arts, while he considered art as related to Constructivism and to the universal. Due to this belief, he criticized Uruguayan artists for not having invented new modes of landscape [painting] and interpreting art, and for continually repeating outdated visual arts formulas. For him, invention in this matter is realized only when the artists create a personal (or his own) mode of interpretation and mediation between the painting, when the artist is capable of actualizing the object when provoked between seeing and thinking with the subjectivity that responds to that provocation. “It is true that the path that has been opened by an artist and his invention, later is at the mercy of the copycats, and then this is transformed into a trend." And he does not disguise his critique of the so-called “Planismo movement” that emerged from the Montevideo art school developed from the TESEO (Agrupación de Artistas y Escritores Uruguayos [Association of Uruguayan Artists and Writers]) group and Círculo de Bellas Artes [Fine Arts Circle] in the 1920s. “And don’t think from this criticism those with modernistic pretensions are excluded because they present green and blue in the canvases of their portraits or in the academies and very thing they create is made of cardboard and in sections as if cut with a knife. (Students be alerted! Don't be fooled!)” Although he did not name names, this irony was directed at José Cúneo, Guillermo Laborde, and Domingo Bazurro among others, who were the main teachers responsible for this trend during the thirties and forties—artists with whom he did not have any explicit difference of opinion or personal friction. One cannot fail to point out the controversy that was created with the “invention of art” and that was advanced by this conference regarding the TTG (Taller Torres García [Torres García Workshop]) and that would take place ten years later in 1946 due to the raving artistic critique made by Tomás Maldonado (one of the principal members of the Argentinean group Arte Concreto-Invención) directed against Joaquín Torres García and published in the bulletin distributed by the group. [For additional reading, please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following texts written by Joaquín Torres García: “Con respecto a una futura creación literaria” (doc. no. 730292), “Lección 132. El hombre americano y el arte de América” (doc. no. 832022), “Mi opinión sobre la exposición de artistas norteamericanos: contribución” (doc. no. 833512), “Nuestro problema de arte en América: lección VI del ciclo de conferencias dictado en la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de Montevideo” (doc. no. 731106), “Introducción [en] Universalismo Constructivo” (doc. no. 1242032), “Sentido de lo moderno [en Universalismo Constructivo]” (doc. no. 1242015), “Bases y fundamentos del arte constructivo” (doc. no. 1242058), and “Manifiesto 2, Constructivo 100%” (doc. no. 1250878)].