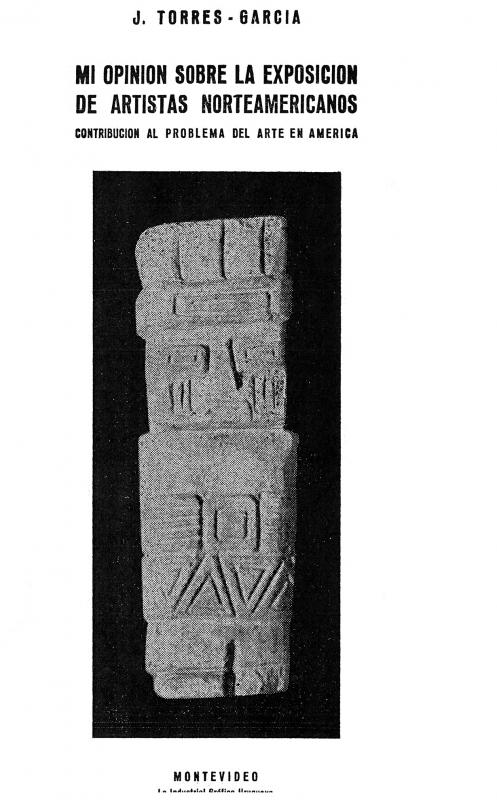

This interpretation of communism in its primitive form, allowed Joaquín Torres García to start this lesson with a sort of “anti-bourgeois faith,” especially by defining himself in complimentary terms such as “bohemian artist,” “altruistic,” and “loving to work.” Without a doubt, this lesson came from those criticisms made by many politically leftist artists, and particularly from the PCU (Partido Comunista Uruguayo [Uruguayan Communist Party]). In the text, Torres García claimed that those goods that constitute the subject’s own life, the “environment” as private property. He does this as an argument about the “personality” of the artist, who in his opinion owes something that is indispensable. In addition, he is thought of as a free thinker, a friend of “literati, poets, artists, and humble people,” which should bring him nearer, from his naive perspective, to the ideas of communism. Nevertheless, what moves him away is the fear of being seen a “regulated” individual, an individual en masse, in the name of a positivism that is alien to his idea of metaphysics. “I want the integral man, the man with spirit with a soul.” He confessed to being mystical and metaphysical “by physiology and by temperament” leaving aside and removed from labels or political classifications. He defended himself from possible accusations of “individualism” that he denied as he detested the concept of “man at the center,” as man was incompatible with total universal harmony. He questioned “proletarian art, such as the communists would want” and he inclined to “practice traditional classical art, that was figurative and anecdotal, only to revamp it with the literary concept of the new social ideology.” Torres García’s critique of social realism was strictly aesthetic and not about ethics, although it also had a political ingredient, by the argument that “official art,” the art at the service of the powerful, was “slavery art.” It should be noted that these criticisms of social naturalism were present at the same moment in 1942 when the strong influence of these artists with such tendencies was felt in Montevideo, encouraged by the visits and exhibitions by those Argentineans who gravitated to David Alfaro Siqueiros, Antonio Berni, Lino Enea Spilimbergo, and Demetrio Urruchúa. It is deeply revealing in the sense that for Torres García the symbol is in the art, so much so that it is raised in the final paragraph of the lesson. “The greatest work of art that the communist has done, is that sickle and that hammer that has been drawn on any wall, with charcoal or with a bad brush. Because that symbol is perfectly a work in visual arts and is written with the heart.” [For additional reading, please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following texts written by Joaquín Torres García: “Con respecto a una futura creación literaria” (doc. no. 730292), “Lección 132. El hombre americano y el arte de América” (doc. no. 832022), “Mi opinión sobre la exposición de artistas norteamericanos: contribución” (doc. no. 833512), “Nuestro problema de arte en América: lección VI del ciclo de conferencias dictado en la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de Montevideo” (doc. no. 731106), “Introducción [en] Universalismo Constructivo” (doc. no. 1242032), “Sentido de lo moderno [en Universalismo Constructivo]” (doc. no. 1242015), “Bases y fundamentos del arte constructivo” (doc. no. 1242058), and “Manifiesto 2, Constructivo 100%” (doc. no. 1250878)].