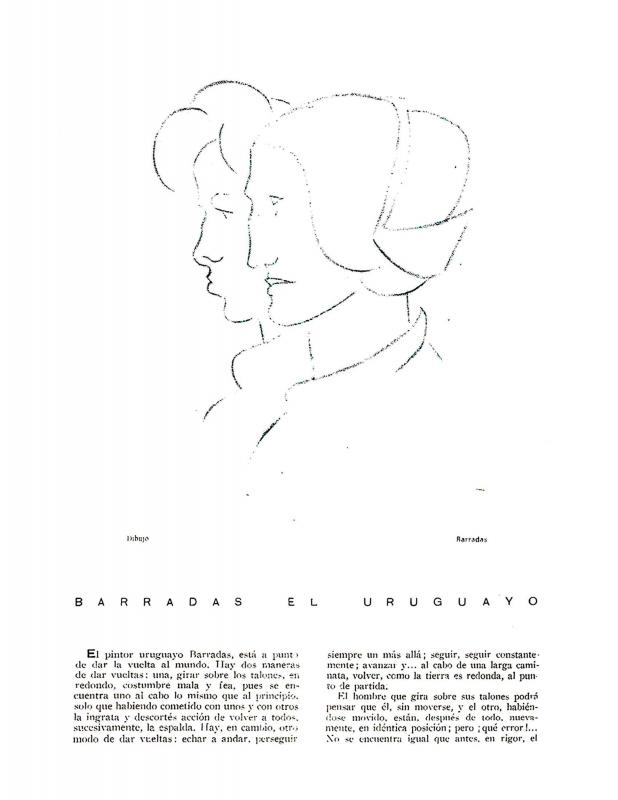

The author, journalist, translator, and art critic Manuel Abril (1884−1943) wrote an analysis of the work of the Uruguayan artist Rafael Barradas (1890−1929) for the Barcelona magazine Vell i Nou [The Old and The New] that was later published in the Barradas exhibition catalogue, an exhibition that took place in Montevideo in 1930. [Please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following texts on the subject: “Rafael Barradas,” by Vicente Basso Maglio (doc. no. 1243440) and “Barradas pintor de eternidad,” by Artur Perucho (doc. no. 1243392)]. He was an admirer of the artist (the Uruguayan had also illustrated various children's books that had been written by Abril, had also illustrated the theatrical scenography of another work by the author titled El portal de Belén), and shared with the artist distinct moments during the artistic renaissance of Spain. Both participated in Madrid’s artistic gatherings and events at the time, and they were also both linked to the rejuvenated groups and artistic movements in literature, theater, and the visuals arts in the country. Moreover, they collaborated on the same magazines such as Tableros, Alfar, and Ultra, among others. Vell I Nou, a publication from Barcelona edited by Galerías Layetanas on which they collaborated, also counted Joaquín Torres García (1874−1949) among its contributors. In this essay, Abril affirms the dual parental affiliation of Barradas, that is, a Uruguayan son of Spaniard parents [Please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following text: “Barradas el uruguayo,” by Julio J. Casal (doc. no. 1197352)]. For the author, the South American artist conjugated the new European proposals of “isms” addressing the cultural needs of his time and place. Abril points out his anti-academic and revolutionary character, as well as his sometimes algebraic creations that were appropriately cubistic, his dynamics with the strong life forces appropriately futuristic, and his disproportionate primitive core or Fauvist [influence]. The author felt his creations and trials were due to his predisposition for something new, although pointing to his “consistency and his work” and the zeal and intangible kinship of renovation echoing the history of art and modernism is what emerges from what Barradas sees in its relation to the towns, people, and cities of Spain. That is, he chooses his themes and visual artistic ideals with the capacity of creating and emerging intrinsic, nonliterary characteristics from these visual artistic concepts. There is the gift of unraveling “the object he is representing” so that the “isms” emerge from a reality without false aspects.