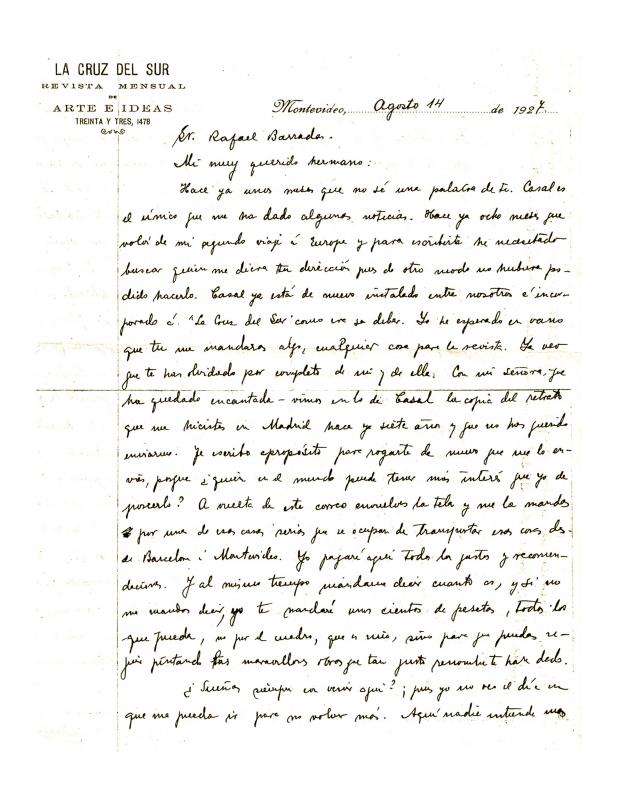

Manuel Abril (1884–1943) was an important player in the lively Spanish cultural scene between the first decade of the twentieth century and the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). He met Uruguayan artist Rafael Barradas (1890–1929) at gatherings in cafés in Madrid. Their vital friendship would lead to joint projects: Barradas illustrated books by Abril and worked on the sets for his plays for children performed at the Teatro Eslava, and Abril wrote on the painter’s work. Both contributed to forward-looking publications like Horizonte, Tableros, Ultra, and Alfar.

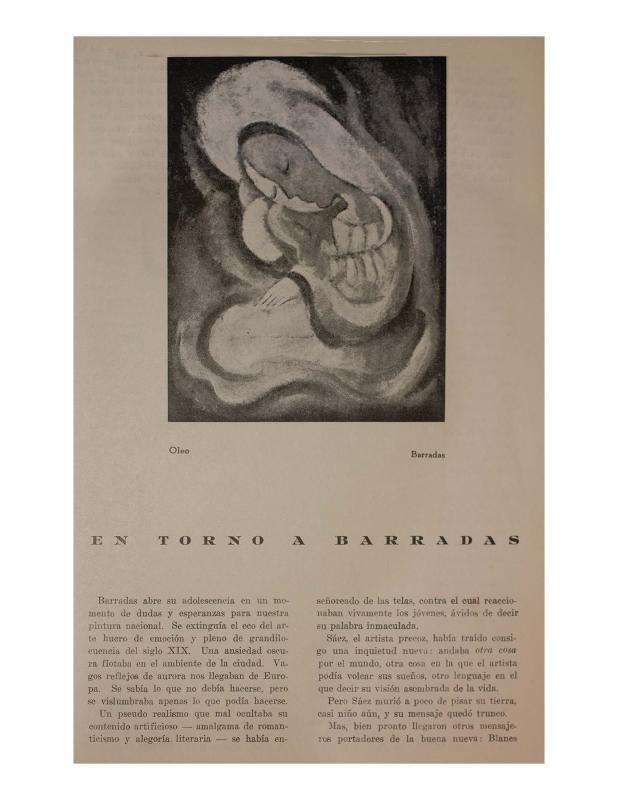

This essay is of interest for a number of reasons, starting with its title: “Barradas el uruguayo” (Barradas the Uruguayan). Barradas’s foreign origin, his otherness as someone who, though from the Americas, formed part of Europe, is highlighted. The main topic of Abril’s essay is a change in Barradas’s work as he moved away from “flat vibration” that combined the resources of the European avant-gardes with images of the ups-and-downs of urban life—a vision that had caused a stir not long before. When, in 1922, Barradas’s work veered toward simple, solemn, and motionless rural figures in earth tones, the response was disconcertion. It appears that Abril justified that change as just another exercise carried out by an artist who was constantly experimenting: change was innate to his art. Abril reviews the various “isms” that Barradas explored (planismo [related to flatness], vibracionismo [related to vibration],and simultanism); he ventures to assert that there is, in the artist’s work, “just a little bit of Futurism, and a very little bit of Cubism,” whereas most other critics saw Barradas’s production as a personal synthesis of those two tendencies. The text has a subtle overtone of rebuke of those who reject the change in Barradas’s work; Abril sees it as evidence of the artist’s growing vitality, contrasting his contemporary attitude of experimentation with the position of artists who have not reacted in any way to the revolution of the avant-gardes. It is likely that Abril viewed the changes in Barradas’s production as bound to the “rappel à l’ordre” that ensued in art after World War I, a “return to order” that did not mean a return to an obsolete artistic language.

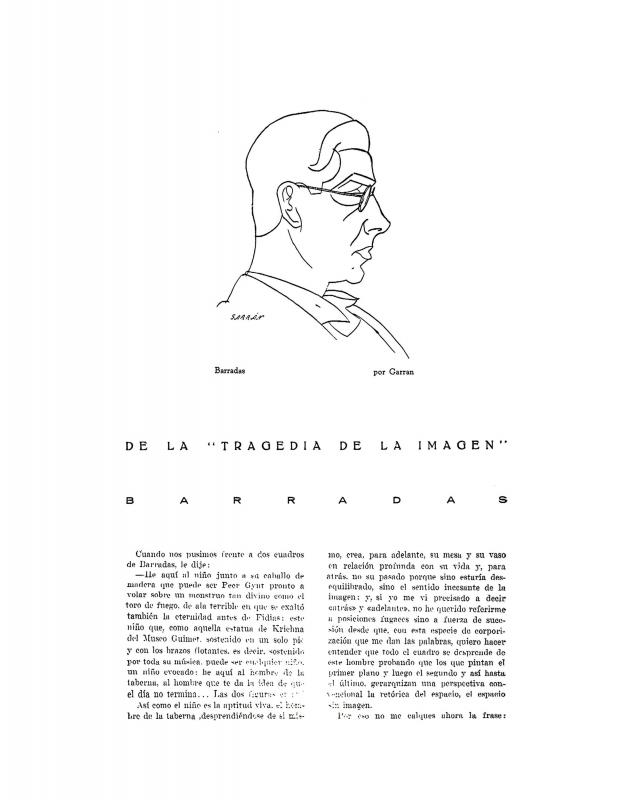

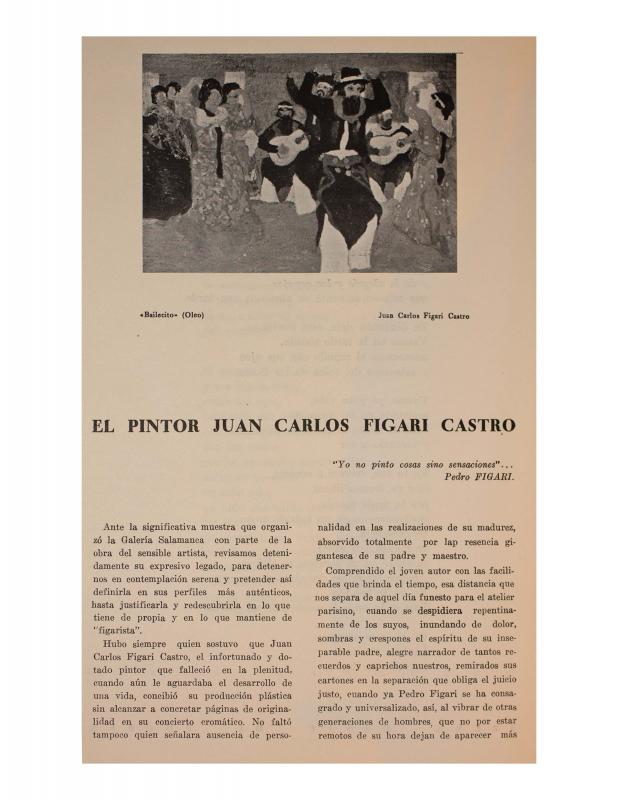

[For further reading, see in the ICAA digital archive the following texts: also by Manuel Abril “Barradas” (doc. no. 1243461); Artur Perucho’s “Barradas pintor de eternidad” (doc. no. 1243392); Alberto Lasplaces’s “Carta a Rafael Barradas” (doc. no. 1250919); Vicente Basso Maglio’s texts “De la Tragedia de la Imagen [Barradas]” (doc. no. 1225969) and ”Rafael Barradas” (doc. no. 1243440); Cipriano Santiago Vitureira’s “Emoción ante Barradas” (doc. no. 1218884); Joaquín Torres García’s “Los artistas uruguayos en Europa: Rafael Barradas” (doc. no. 1228429); Jorge Páez Vilaró’s “El pintor Juan Carlos Figari Castro” (doc. no. 1228547); and Clotilde Luisi’s “En torno a Barradas” (doc. no. 1227809)].