The first thing that Joaquín Torres García (1874−1949) did was rectify the erroneous biographical data presented in the article by N.B. (Norberto Berdía, 1900−83) pointing out, among other things, that it was not in Paris, but in Fiesole, “well away from the great capitalistic cities” where he began to conceive his theory of an art “that would be for all times and for all men.” The master reaffirmed himself in a radical individualism when he argued that his art was not for the people, but neither for the bourgeois nor for any of the elite. “I only follow my thoughts.” Consequently, this assertion by JTG was directed against the notion of an “affiliated individual” that implicitly operated within a political partisanship of an art that conventionally was identified as “social realism”. The author felt he was in conflict not only with Berdía but also with the Marxist philosophy itself that his artist represented according to the provincial version of the CTIU (Confederación de Trabajadores Intelectuales del Uruguay [Confederation of Intellectual Workers of Uruguay]). He underlined: “To follow one’s thoughts in accordance with Marxism, is a crime.” And then asking himself, “On entering a Marxist ideology I will then be a good artist?”

On the other hand, as for the argument that he was a bourgeois artist supported by the romantic notion of genius, JTG responded angrily: “This art of mine and by the way it was conceived, could become an impersonal collective art.” He then followed with the planting of the notion of a “collective art” on a plane that is practiced by a collectivity supporting constructivism and thus separating it from the notion of “social realism” for which collective art represents topics and social conflicts concerning the collective. The critique regarding the embedded nationalisms that JTG suggested was interesting at a time and era of realistic art. He claimed that Hitler fought modern art and the primitivism it involved for its universalism, and for the same reason it had been condemned in Italy, Spain and North America because in the 1930s the United States cultivated a muralism rooted on identity and nationalism.

Finally, the text reaffirmed the radical separation between art and all and any extra aesthetic elements that pretended to join itself, continuing the line of aesthetic specificity that was consecrated by the modernist movement. JTG said it crudely, “[N.B. craves] “propaganda art, which would correspond to a time that was also constructive but not a constructive art”.

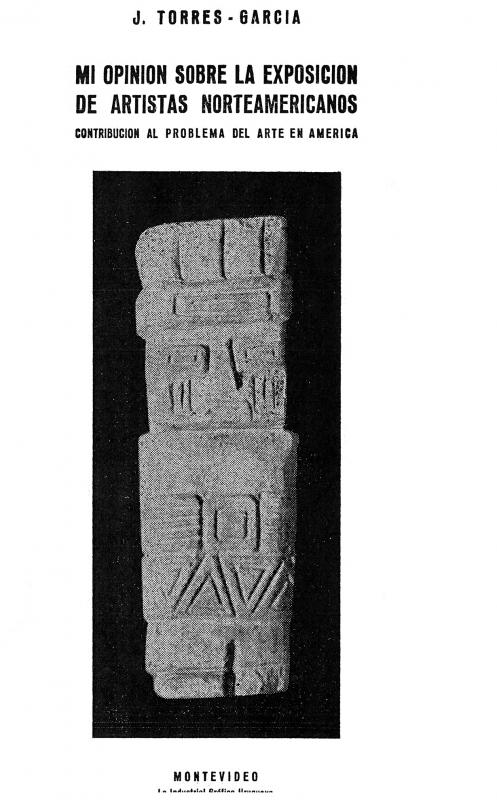

[For further reading, please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following texts written by Joaquín Torres García: “Con respecto a una futura creación literaria” (doc. no. 730292), “Lección 132. El hombre americano y el arte de América” (doc. no. 832022), “Mi opinión sobre la exposición de artistas norteamericanos: contribución” (doc. no. 833512), “Nuestro problema de arte en América: lección VI del ciclo de conferencias dictado en la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de Montevideo” (doc. no. 731106), “Introducción [en] Universalismo Constructivo” (doc. no. 1242032), “Sentido de lo moderno [en Universalismo Constructivo]” (doc. no. 1242015), “Bases y fundamentos del arte constructivo” (doc. no. 1242058) and “Manifiesto 2, Constructivo 100%” (doc. no. 1250878)].