The argument made by Joaquin Torres Garcia that the artist “does not make himself” but is born an artist, was for Joaquín Torres García (1874−1949) the premises on which he would start his reflections. Pointing to his immanentist and essentialist concepts on what denotes artistic “genius”, a belief that comes, in part, from his first readings of nineteenth century German Romanticism. The author refers to the exclusive sensitivity of each artist, in his opinion art does not exist, what exists are artists. It is he, the artist, who conforms his personality to be an artist. The task of each artist, therefore, would be to pertain to “his most unprecedented level,” that which is intrinsic and inherent to him. He had dealt with these issues in his earlier writings between 1915 and 1918. Among them, “El descubrimiento de sí mismo” and “Consejos a losartistas” that were published in the Barcelona newspaper El enemic del poble under the care of [John] Salvat Pappaseit.

On the other hand, the concept of “tone” that was linked to color but not the same as “tonal,” (Tonal means the value that a color acquires when situated in a structured chromatic context.) had been developed in his classes in Montevideo as a basic concept around the second half of the 1930’s along the same lines, with the concepts of “form” and “structure.” Here, Joaquin Torres Garcia proclaimed the indivisible unity between the concepts “form,” “material,” and “tone,” considering these as a dynamic union, an interactive triad, where art is not only constructed but rather constructive art is created in general. The “material” is the concrete that is synthesized with the idea that is abstract. In addition, he implies that the plane, in his opinion, is “where the painting is drawn and must remain.” Moreover, by affirming the concept of “construction”, Joaquin Torres Garcia also proclaims unity between the drawing and the color (tone) where both are constituted as substantive parts of the act of constructing.

The article had veiled references to his eternal enemies, the figurative artists and the provincial art critics. He had reserved for the figurative artists (whom he considered cultivated a “pseudo-art”) his reflections on the “freedom of creating art,” because he argued they lacked freedom and therefore were subjected to imitation. He gives precedence to the rules of constructivism, which are nothing more than an instrument to exert the creative freedom of the artist within the thought and intuition of “the abstract”. Secondly, he dedicates his ideas to the provincial critics for their inability to verbalize art either by pretense of interpretation or description.

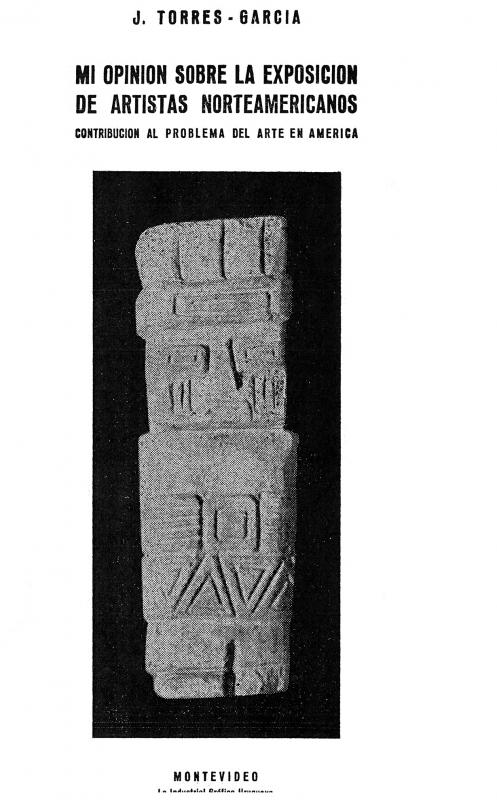

[Please refer to the ICAA digital archive for the following additional texts written by Joaquín Torres García: “Con respecto a una futura creación literaria” (doc. no. 730292), “Lección 132. El hombre americano y el arte de América” (doc. no. 832022), “Mi opinión sobre la exposición de artistas norteamericanos: contribución” (doc. no. 833512), “Nuestro problema de arte en América: lección VI del ciclo de conferencias dictado en la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de Montevideo” (doc. no. 731106), “Introducción [en] Universalismo Constructivo” (doc. no. 1242032), “Sentido de lo moderno [en Universalismo Constructivo]” (doc. no. 1242015), “Bases y fundamentos del arte constructivo” (doc. no. 1242058) and “Manifiesto 2, Constructivo 100%” (doc. no. 1250878)].