In his book Teseo Discusión Estética y Ejemplos clasicismo impresionismo cubismo futurismo arte nacional (published in 1925), the critic Eduardo Dieste (1882–1954)—who played an important role in Uruguay’s cultural development during the 1920s—identifies the group of visual artists and writers who embraced the spirit of renewal of the times. He discusses the subject matter favored by this group, mentioning the simplicity of their attempts to depict the local landscape and the new techniques they use to explore light and color. Dieste, who had trained extensively in the field of European art, reviews their works from the perspective of what he sees a balanced interpretation of the history of Western art (with a marked emphasis on France). This includes the anti-academic visual art innovations and the new local-criollo poetics that accompanied the social and, especially, political changes of the Batlle period in Uruguay.

Doctrinaire considerations of this kind are included in this essay about the work of the sculptor Bernabé Michelena (1888-1963). The author describes him and praises him as a “contemporary spirit” because of his skills in terms of synthesis and expression, claiming that, while not imitating Auguste Rodin, his production is reminiscent of the latter’s work, “moving the large form within the small form.” Dieste roams the artist’s studio, commenting on the sculpted busts of members of the literary generation of the 1920s, friends from the local café society who gathered in studios, the preferred venues of the Teseo organization that Dieste himself headed. Among others, he identifies Alberto Zum Felde (1888-1976), Enrique Casaravilla Lemos, the gaucho head that the writer Emilio Oribe posed for, etc. Dieste applauds Michelena while deploring the distance that separates these aesthetic novelties from the general public’s taste as reflected in the decisions of state juries. The 1920s produced a rich artistic harvest, thanks to the many competitions organized to celebrate the Centenary of the Constitution with the construction of public buildings and monuments. Against that background, Dieste extols Michelena’s work as seen through the prism of “educating people in a new way of seeing,” which was in step with the country’s new endorsement of art that underscored the “simple stories with which nations sing of their legends.” According to the critic, Michelena discovered a certain kind of sensitive meditation that found a balance between expressive effects and non-sensational formal conditions. The author states that Michelena’s work represents “the most serious art that sculpture has produced so far in Uruguay.”

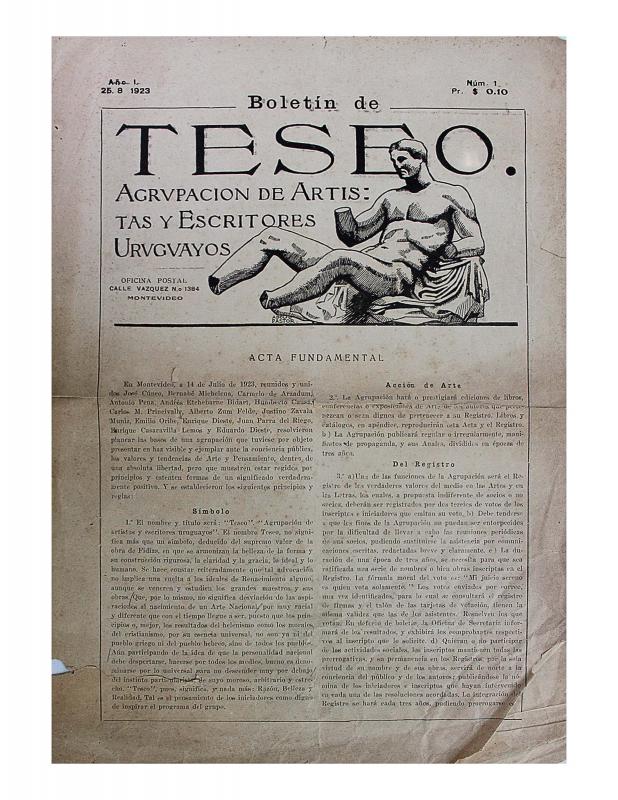

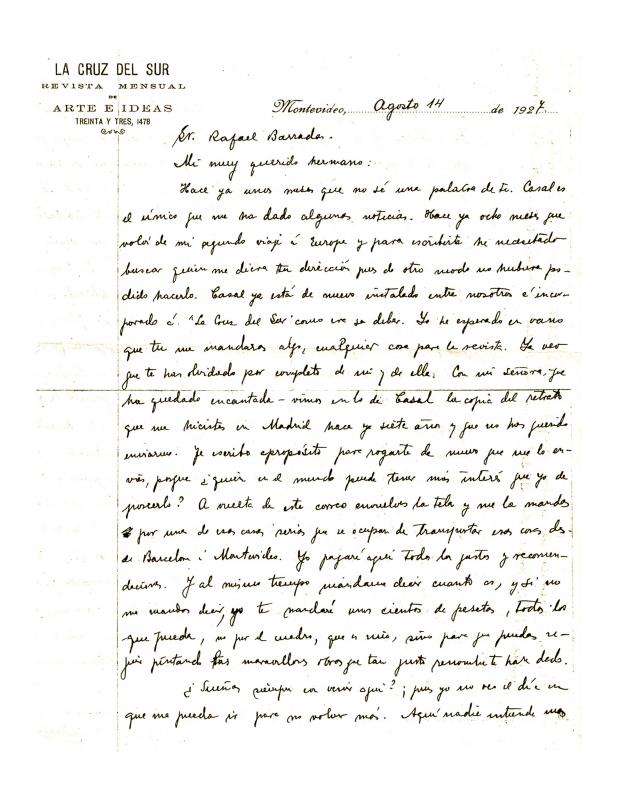

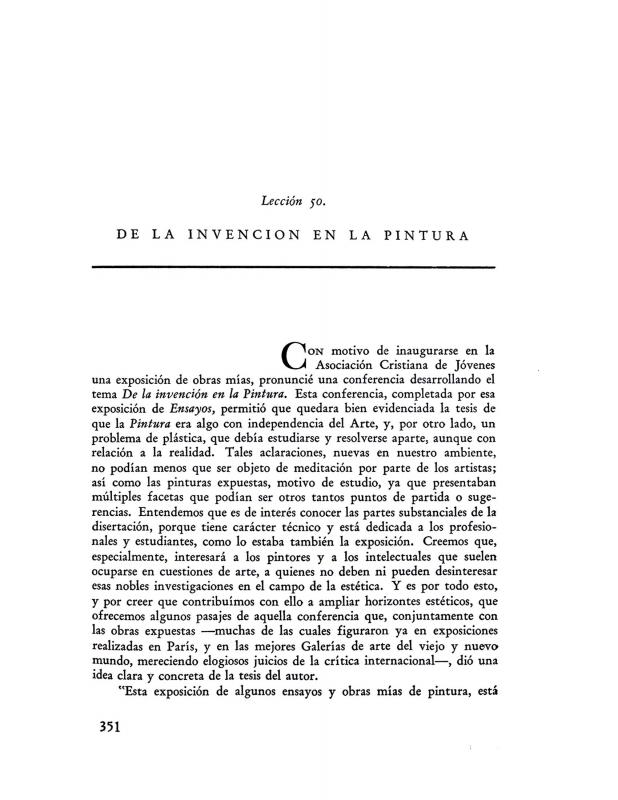

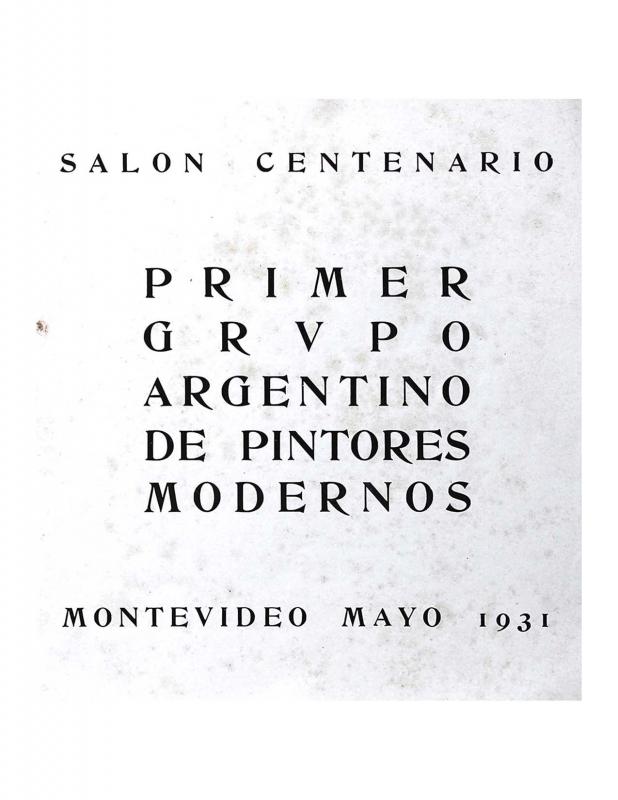

[As complementary reading see, in the ICAA digital archive, the following articles published by TESEO: by Eduardo Dieste, “El Drama de la Pintura, Teseo, Discusión estética y ejemplos” (doc. no. 1217147); “Humberto Causa, otro pintor de la luz” (doc. no. 1221130); “José Cuneo Pintor de la luz” (doc. no. 1217703); and “El Milagro del Prisma [Teseo Discusión Estética y ejemplos]” (doc. no. 1217097). See also: “Boletín de TESEO [Agrupación de Artistas y Escritores Uruguayos],” written by José Cuneo, Bernabé Michelena, et. al. (doc. no. 1182637); “Carta a Rafael Barradas” (doc. no. 1250919); “De la invención en la pintura” (doc. no. 1245854); “Escuela Taller de Artes Plásticas al Ministro de Instrucción Pública [carta institucional en borrador],” by the Escuela Taller de Artes Plásticas (ETAP) (doc. no. 1265434); “Primer Grupo Argentino de Pintores Modernos” (doc. no. 1228165); “Programa,” by Alberto Zum Felde (doc. no. 1196932); “Teseo. Los Problemas del Arte,” by C.L. (doc. no. 1223765); and “Uruguay Olímpico,” by Alberto Lasplaces (doc. no. 1254039)].