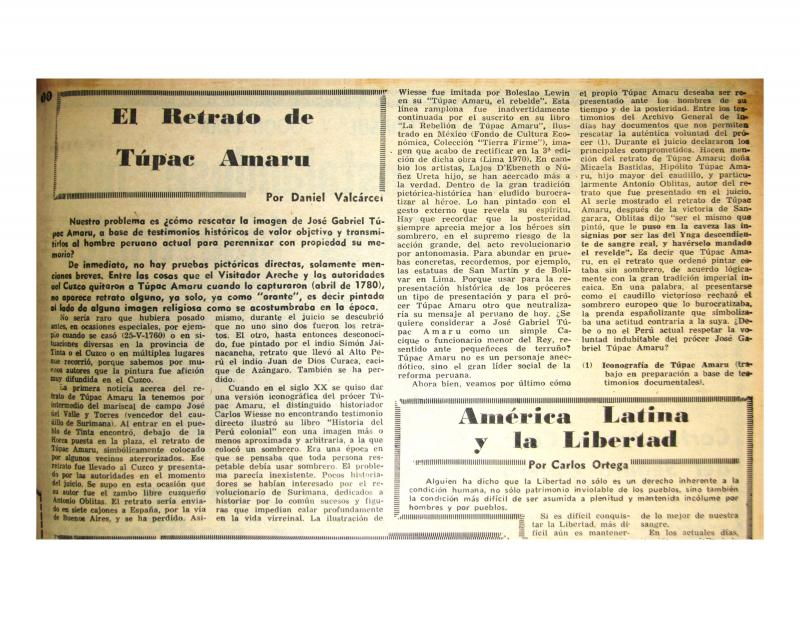

Although the Gobierno Revolucionario de las Fuerzas Armadas (1968–75) under General Juan Velasco Alvarado (1910–77) was particularly interested in cultural policies, this publication contains one of the few direct expressions of the general’s artistic opinions. This is the first explanation of the importance of the “change” in the images that preside over the ceremonial hall in the Palacio de Gobierno; the hall would be officially renamed and its new decorations presented the following day (July 25, 1972). Although this information is not provided in the document, the replacement painting was by Néstor Quiroz López, a police officer assigned to the palace. In 1974, the painting by Quiroz López would be replaced by another image of the hero created by Mario Salazar Eyzaguirre, a captain of the Peruvian army who would later become major general. In 2003, that second painting was replaced by a work by artist Armando Villegas (1926–2013).

The symbolic act of replacing the image of the Spanish conqueror with the image of the indigenous forefather of independence was less controversial than the fact that the work chosen was by Néstor Quiroz López, a humble policeman with a taste for painting. The work replaced a portrait by Daniel Hernández (1856–1932), a recognized academic painter who had even served as the director of the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes from the time of its founding in 1919 through 1932. This indifference to “the specifically artistic” was met with protest from painter de Szyszlo, whose statements were what motivated this response from the president, and from writer Néstor Espinoza (b. 1938), among others [on that subject, see in the ICAA digital archive by Espinoza “Machu Picchu y Túpac Amaru” (doc. no. 1139229)].

This controversy can be seen as a precedent to the one that ensued in 2004 in response to the removal of the monument to Pizarro by North American sculptor Charles Cary Rumsey (1879–1922) placed in the Plaza Mayor in Lima in 1935. The intensity of both debates illustrates the ongoing importance to Peruvians of the trauma of conquest and its subsequent political uses.

[For further reading on Túpac Amaru II, see the following articles in the archive: by General EP Felipe de la Barra “¿Cómo fue Túpac Amaru?” (doc. no. 865441); (unsigned) “Convocan a concurso: monumento a Túpac Amaru se levantará en el Cuzco” (doc. no. 1053438); by Alfredo Arrisueño Cornejo “Convocan a concurso de pintura para perpetuar la imagen plástica del mártir José Gabriel Condorcanqui” (doc. no. 865422), and “Declaran desierto el Concurso de Pintura ‘Túpac Amaru II’” (doc. no. 865498); (unsigned) “En busca de la imagen arquetípica de Túpac Amaru” (doc. no. 865702); by Daniel Valcárcel “El retrato de Túpac Amaru” (doc. no. 1052165); and by A. O. Z. “Túpac Amaru: ¿verdadero retrato?” (doc. no. 865460)].