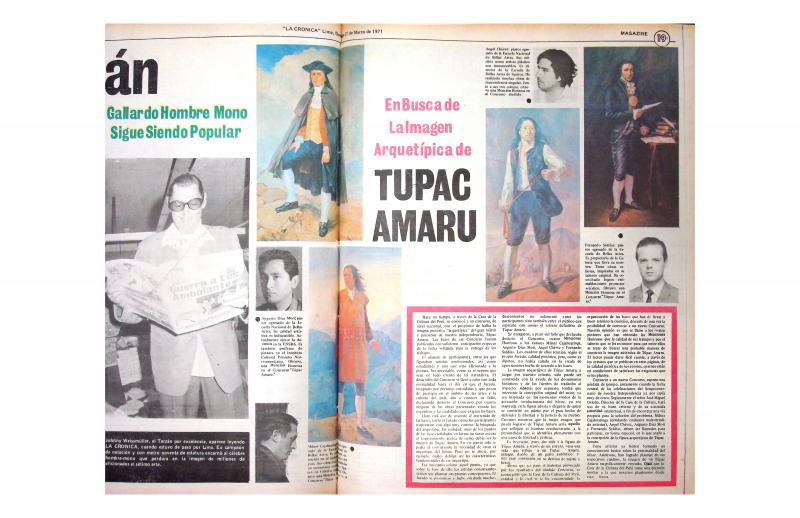

In this document, man of letters Néstor Espinoza (b. 1938) responds to the letter from painter Fernando de Szyszlo (1925–2017) published in the magazine Oiga (Lima, August 4, 1972), in which the latter expresses his artistic—and, he clarifies, not political—reservations about the replacement of the portrait of Spanish conqueror Francisco Pizarro (1476–1541) with the portrait of the indigenous forefather of independence, Túpac Amaru II, in the main hall of the Palacio de Gobierno. This text by Espinoza can be read as expressing the governmental position since the newspaper Expreso, in which it was published, had been appropriated by the military regime in 1970, and it fervently upheld the position of that regime. The first period of the so-called Gobierno Revolucionario de las Fuerzas Armadas (1968–75) was characterized by social reform and by an interest in symbolic representation. Its emblem was the figure of Túpac Amaru II (José Gabriel Condorcanqui, 1738–81), a curaca or chief of Incan descent who, in 1780, led the most important Andean uprising against the Spanish empire, an event largely ignored in traditional Spanish-American historiography. Between 1970 and 1971, an art competition was held in order to obtain an official image of the indigenous hero, but was ultimately declared null and void. The symbolic act of replacing the image of the Spanish conqueror with the image of the indigenous forefather of independence was less controversial than the fact that the work chosen was by Néstor Quiroz López, a humble policeman with a taste for painting. The work replaced a portrait by Daniel Hernández (1856–1932), a recognized academic painter who had even served as the director of the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes from the time of its founding in 1919 through 1932. This indifference to “the specifically artistic” was met with protest from painter de Szyszlo, whose statements were what motivated this response from writer Néstor Espinoza. In 1974, the painting by Quiroz López was replaced by another image of the same hero created by Mario Salazar Eyzaguirre, an army captain who would later become major general. In 2003, that second version was replaced by a work by artist Armando Villegas (1926–2013). This controversy can be seen as a precedent to the one that ensued in 2004 in response to the removal of the monument to Pizarro by North American sculptor Charles Cary Rumsey (1879–1922) placed in the Plaza Mayor in Lima in 1935. The intensity of both debates illustrates the ongoing importance to Peruvians of the trauma of conquest and its subsequent political uses. [For further reading on Túpac Amaru II, see the following articles in the ICAA digital archive: by General EP Felipe de la Barra “¿Cómo fue Túpac Amaru?” (doc. no. 865441); (unsigned) “Convocan a concurso: monumento a Túpac Amaru se levantará en el Cuzco” (doc. no. 1053438); by Alfredo Arrisueño Cornejo “Convocan a concurso de pintura para perpetuar la imagen plástica del mártir José Gabriel Condorcanqui” (doc. no. 865422), and “Declaran desierto el Concurso de Pintura ‘Túpac Amaru II’” (doc. no. 865498); (unsigned) “En busca de la imagen arquetípica de Túpac Amaru” (doc. no. 865702); by Daniel Valcárcel “El retrato de Túpac Amaru” (doc. no. 1052165); and by A. O. Z. “Túpac Amaru: ¿verdadero retrato?” (doc. no. 865460)].