An important intellectual from Cuzco, José Uriel García (1884–1965) was closely tied to Indianism. His article on José Sabogal sheds light on the main ideas of his nationalist theory of cultural mestizaje developed in his influential book El nuevo indio (Cusco: H. G. Rozas Sucesores Librería e Imprenta, 1930). (The prologue to the book and its sixth chapter are included in the ICAA digital archive, doc. no. 1136663 and doc. no. 1136679, respectively.) It is interesting to compare García’s view of Sabogal and his view of Martín Chambi, a photographer from Cuzco (his thoughts on Chambi are expressed in an article published in the magazine Excelsior (Lima, August and September, 1948)). Regarding the painter, García looks to the idea of historical determinism, whereas with Chambi, he looks to ethnic determinism.

A second strain of Indianism—known as “neo-Indianism,” in reference to the title of the book El nuevo indio by José Uriel García, the main framer of the movement—took hold in Cuzco in the twenties, thirties, forties, and fifties. This movement contrasted with an earlier “Incanist” strain of Indianism led by Luis E. Valcárcel, a movement whose tenets were voiced in his book Tempestad en los Andes (1927). Whereas Valcárcel argued that the true native identity as well as contemporary indigenous culture should be envisioned as a vestige of the Incan, García proposed that “the Andean” be seen as an innovative reality, product of a fusion of native and Hispanic elements. García’s nationalist theory contained three parts: “El indio antiguo” (the Indian of the past), “El nuevo indio” (the new Indian), and “El pueblo mestizo” (the mestizo people) which—according to García’s idealist vision—came together to form “the Indian” in the different periods of Peruvian history. The prologue outlines the basis of the proposal, expressing a desire to replace ethnic determinism with historical and social consciousness. The book was first published in 1930; a second, amended version was published in 1937; and a third edition was published in 1973. Despite his ideological differences with García, Valcárcel edited that third version, which was published after García’s death and before he had time to finish revising it; this third edition, which included an appendix by García, evidences García’s theoretical orientation in his final years when his thinking was informed by Marxist thought.

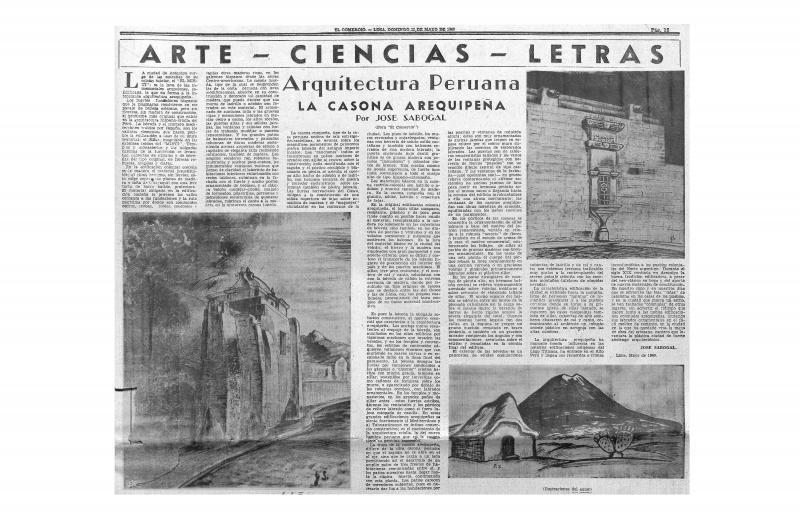

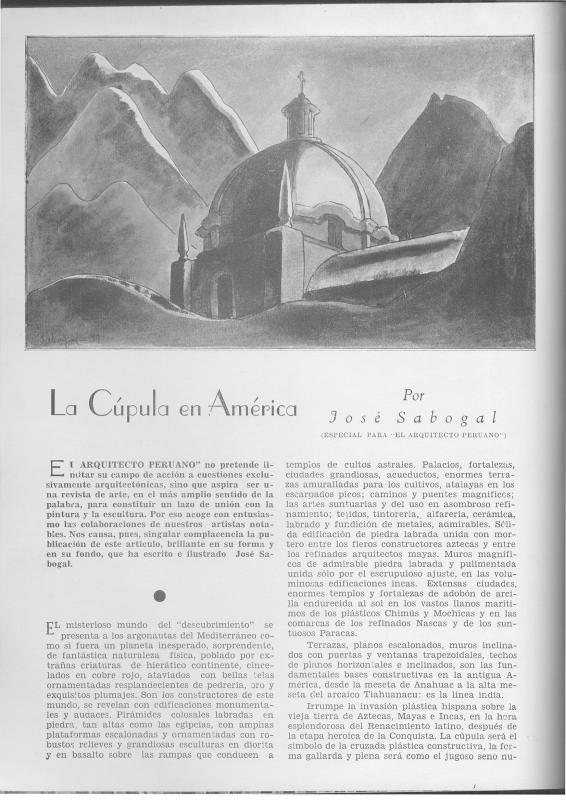

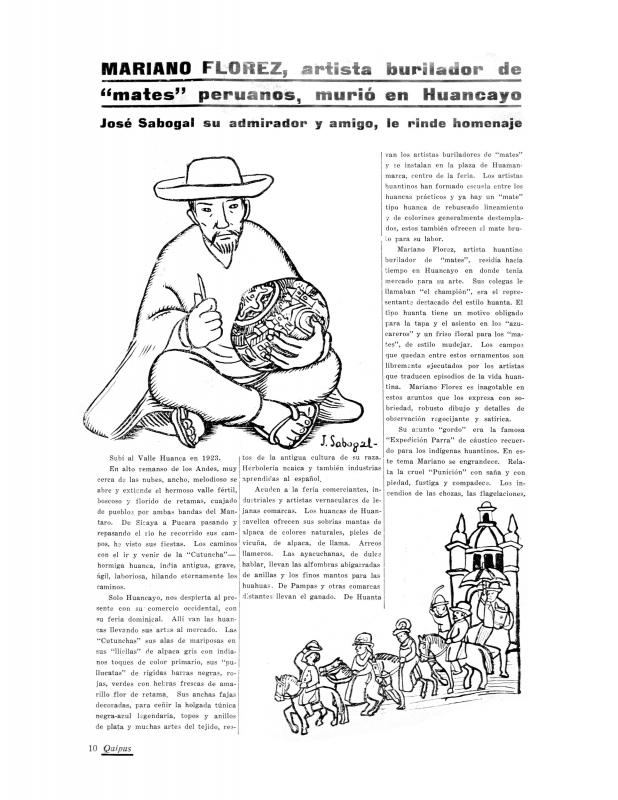

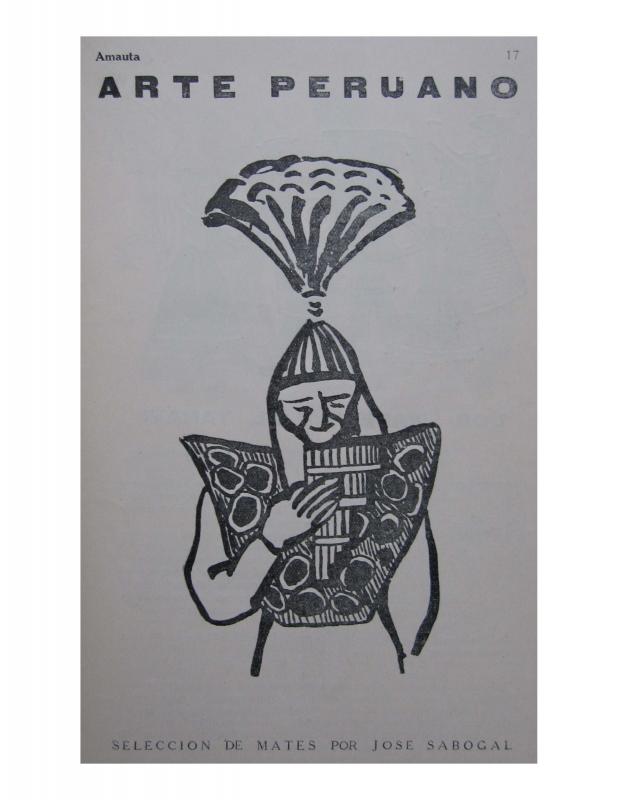

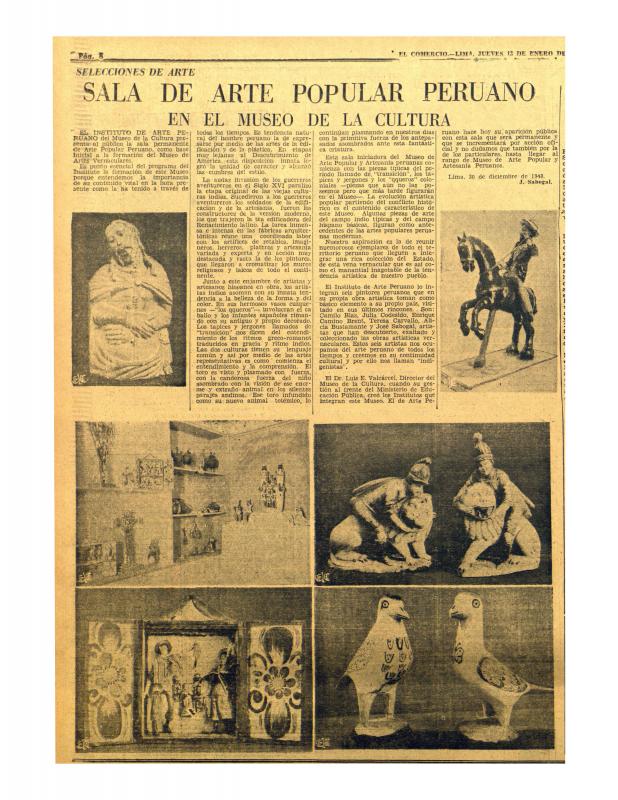

There are many texts on Sabogal in the ICAA digital archive, including the following written by the painter himself: “Arquitectura peruana: la casona arequipeña (doc. no. 1173340), “La cúpula en América” (doc. no. 1125912), “Mariano Florez, artista burilador de "mates" peruanos, murió en Huancayo: José Sabogal su admirador y amigo, le rinde homenaje” (doc. no. 1136695), “Los mates burilados y las estampas del pintor criollo Pancho Fierro” (doc. no. 1173400), “Los 'mates' y el yaraví” (doc. no. 1126008), “La pintura mexicana moderna” (doc. no. 1051636), and “Sala de arte popular peruano en el Museo de la Cultura : selecciones de arte” (doc. no. 1173418).