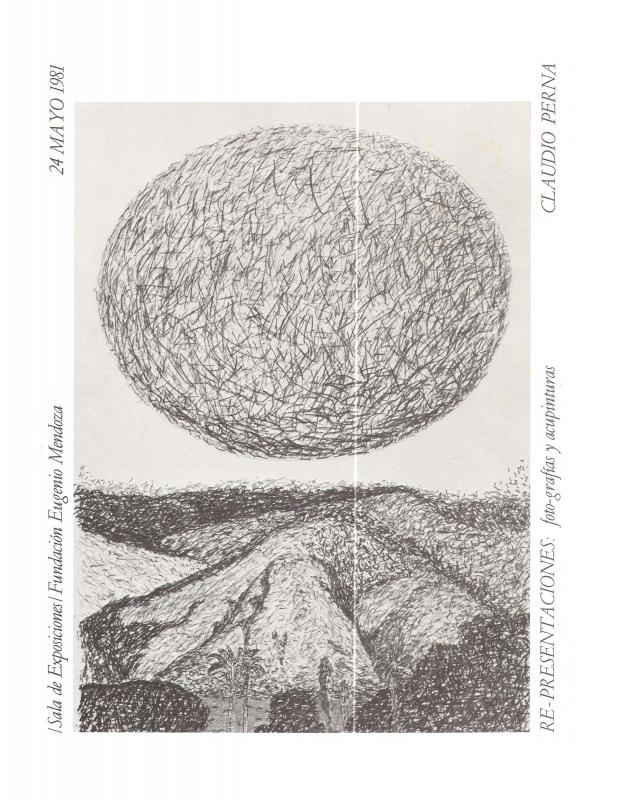

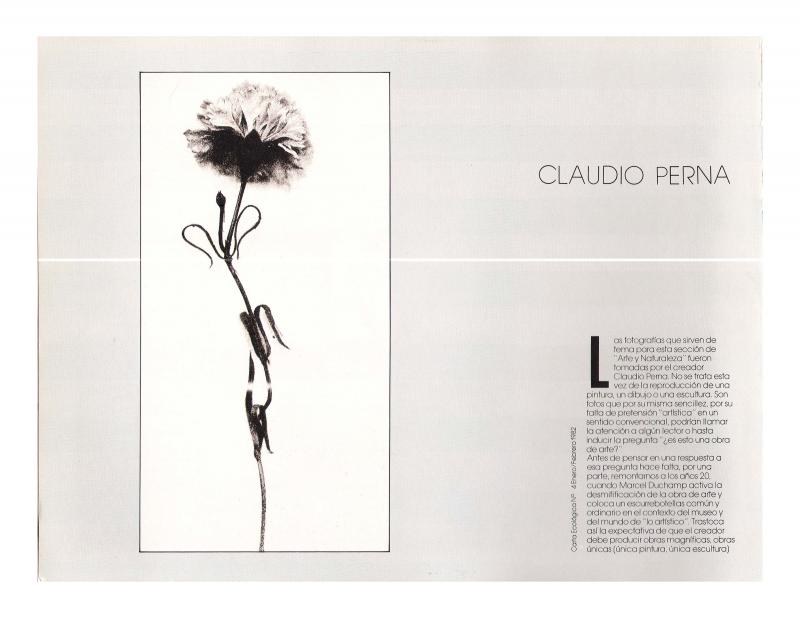

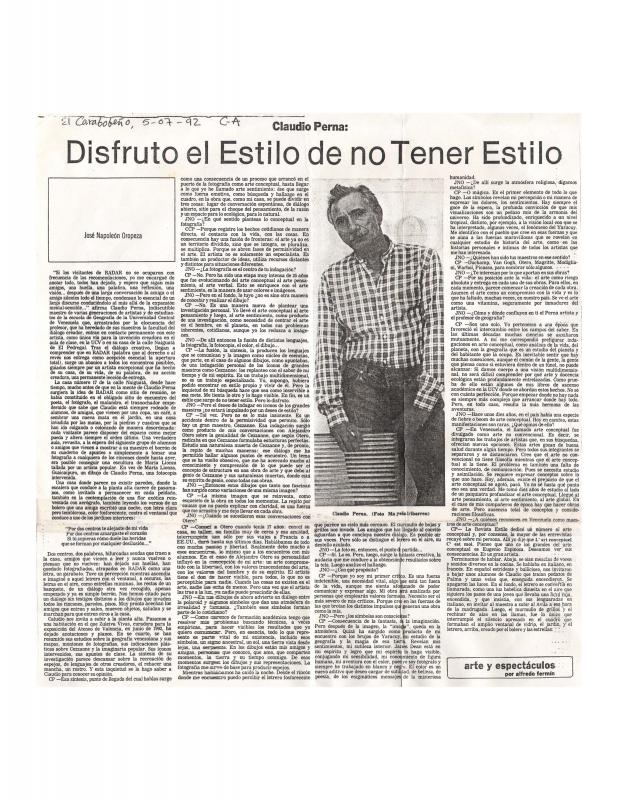

This is the journalist Mara Comerlati’s review of Re-presentaciones: foto-grafías y acupinturas, the exhibition of works by the Italian-Venezuelan geographer and conceptual artist Claudio Perna (1938–97) at the Sala Mendoza (Caracas, 1981). The essay makes two very interesting points. In the first place, Comerlati cites Perna as an example and calls attention to a constant phenomenon in Venezuelan cultural circles, which is a resistance to anything new. The journalist quotes Perna who, “somewhat wistfully” says: “I am forty-two years old and I am still considered a ‘young artist’…” Comerlati says that, in her opinion, “it sounds like a complaint because Claudio has spent many years working, thinking, and distilling his artistic view of reality.” Perna had remarked that, being “a man of his time, aware of his circumstances and clear-eyed in his analysis of current events” he can see that, in Venezuela there is scant ability to appreciate new things in general and, in particular, new ideas in our local art. In his opinion, this is because the average Venezuelan does not understand artists, since they move in “circles that never overlap.” In other words, “celebrated artists are on a level with political figures, but those who have introduced Venezuela to contemporary art are ignored.” In the second place, Comerlati points out that her review re-examines the country’s collective memory, and explains that Perna does it by re-interpreting the names, subjects, and examples of classical Venezuelan painting (since the Colonial period) in order to recreate them “as seen from a contemporary perspective and with a certain amount of humor.” As, for example, in the case of Nuestra Señora de la Merced, an emblematic image of Caracas by an anonymous colonial artist, reinterpreted by Perna with an aerial view of the freeway and modernity at his feet. Or, his portraits of his artist friends, such as Héctor Fuenmayor, and his variation on a theme (the macaws) by Alberto and Federico Brandt.

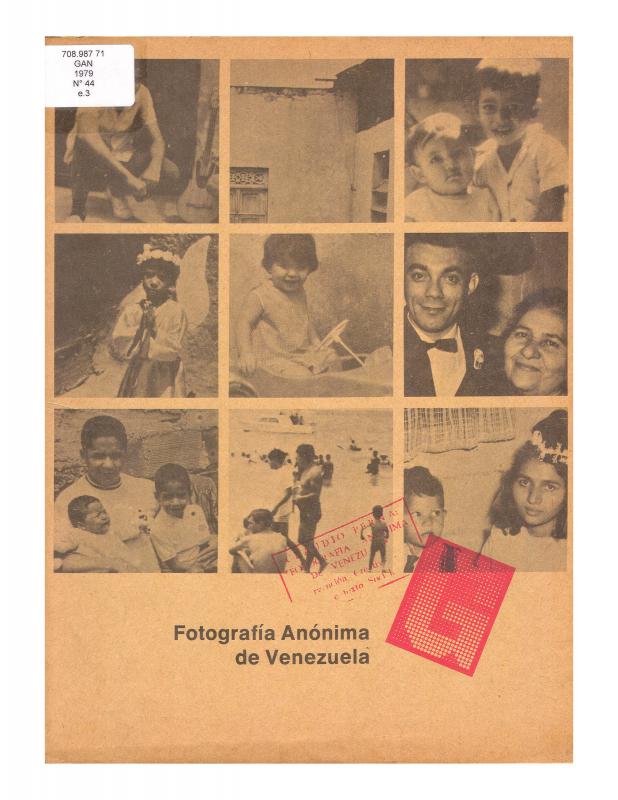

Comerlati also briefly touches on a subject of great interest to the critics: Perna’s use of “marginal” media, such as photocopies and Polaroids, which he sees as resources that are no different to any other technique.

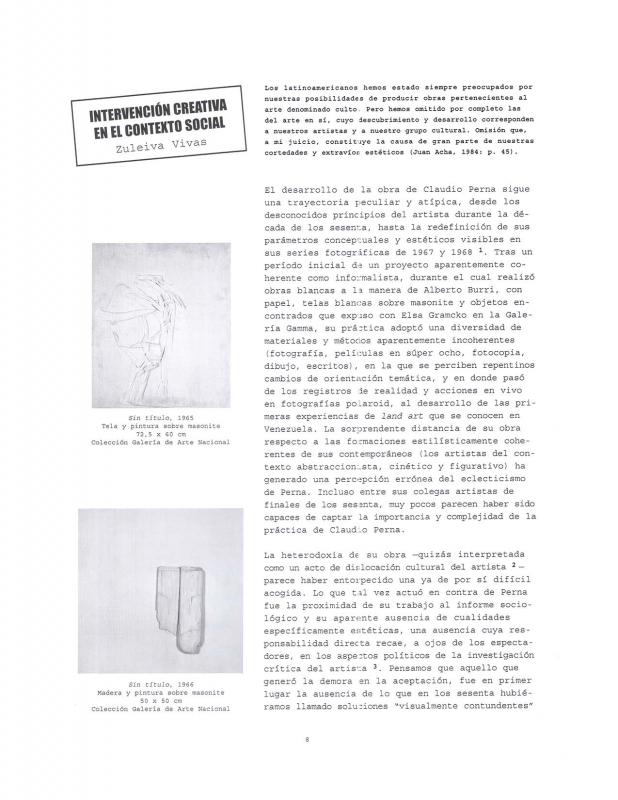

What Perna said in 1981 about his work being misunderstood, and about meager support from cultural authorities and a discrete segment of the public, was certainly not baseless. His work was not fully acknowledged until 2004 when it was the object of a major exhibition at the Galería de Arte Nacional, curated by Zuleiva Vivas, the cofounder (with a group of the artist’s friends) of the Foundation that bears his name.

To read other articles about this artist, see by Margarita D’Amico “1: Hoy es arte lo que no era” [doc. no. 1068360]; by Luis Enrique Pérez-Oramas “El autocurrículum de Claudio Perna, escultura social y novela hiperrealista” [doc. no. 1161917]; by Roberto Guevara “Claudio Perna o cómo ser libre en la marginalidad” [doc. no. 1080814]; by Elsa Flores “(Sin título) [Vivir quiere decir dejar huellas…]” [doc. no. 1063156]; by María Elena Ramos “Arte–idea–geografía” [doc. no. 1080766]; by José Napoleón Oropeza “Claudio Perna. Disfruto el estilo de no tener estilo” [doc. no. 1067382]; and, by Lourdes Blanco “Claudio Perna: fotocopias” [doc. no. 1080715]. See also the following articles by Zuleiva Vivas: “Las opciones del tiempo para el nuevo espíritu” [doc. no. 1065674]; “Visión panorámica de las nuevas cartografías” [doc. no. 1157158]; “Los nuevos procesos y la representación figurativa” [doc. no. 1157174]; “Intervención creativa en el contexto social” [doc. no. 1161969]; and “Claudio Perna y el arte del pensamiento” [doc. no. 1163950].