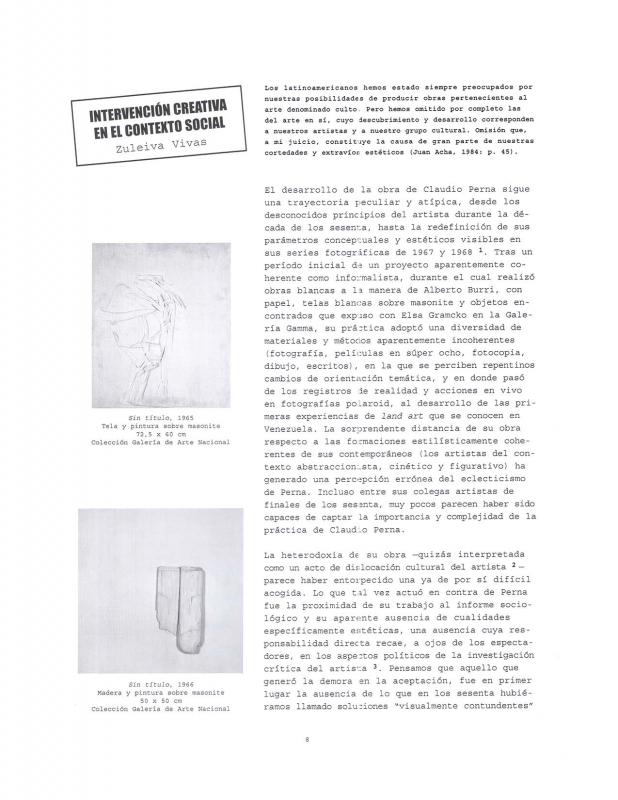

The writer José Napoleón Oropeza (b. 1949) interviewed the Italian-Venezuelan geographer and artist Claudio Perna (1938–97) at the latter’s home-studio in Caracas during preparations for the exhibition Venezuela desde el cielo (jointly undertaken with the curator Zuleiva Vivas) that was presented in June 1992 at the Ateneo de Valencia (in the Venezuelan state of Carabobo) which, at the time, was directed by Oropeza. The interview, which was published after the exhibition opened, introduced this artist’s work to a city where he was not very well known, and therefore addressed a variety of subjects. Oropeza describes Perna as a tireless artist who is a passionate conversationalist. He also describes (in a story-telling, narrative style) his home-studio located in a leafy neighborhood, a space that seems to have no walls, where paintings, sculptures, and papers are scattered about in no apparent order. Oropeza notes that Perna is engaged in teaching an ongoing “lesson about dedication and commitment.”

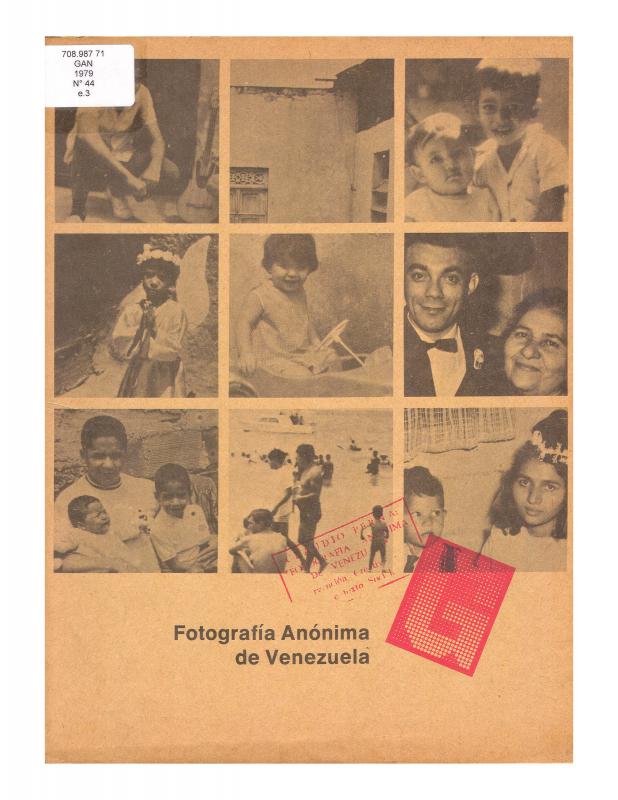

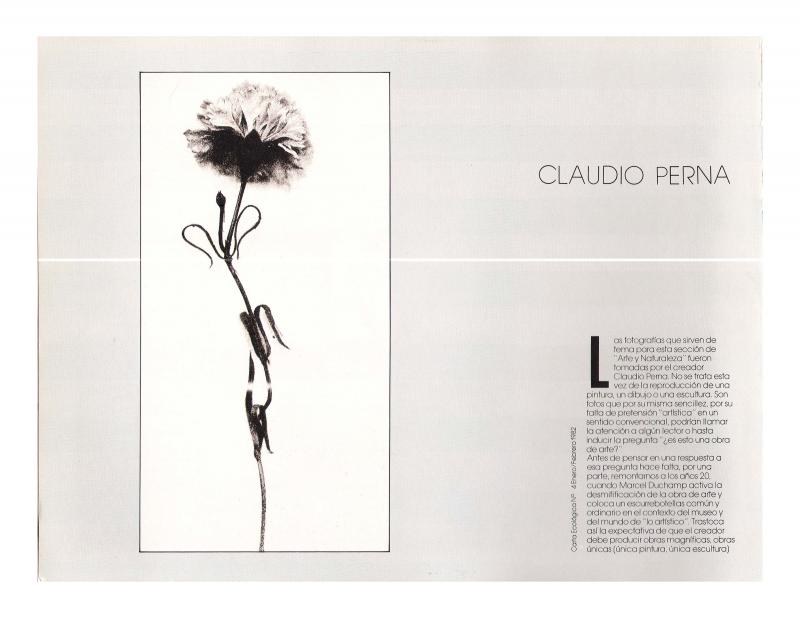

One of the most important items mentioned in this interview is Perna’s explanation of what he considers to be the fundamental concepts in his work, which he describes as “thought art” and/or “feeling art;” both these terms are derived from his own personal interpretation of conceptual art. His current work can be seen as a synthesis (or point of arrival) based on a process that “departed from the port of photography as conceptual art, and docked at what I refer to as feeling art, the kind of art that expresses emotional feelings.” Perna’s description of human creativity is seasoned with words he draws from the field of geography and applies to the world of art, such as “port” and “frontier.”

On the whole, the interview conveys a sense of Perna’s importance in the field of Venezuelan conceptual art, and underscores his standing as an example of a comprehensive life/art experience. Perna sees no boundaries between creating art and teaching an awareness of ecology. He explains that his work includes “searching and finding” which, as in the case of his house, can be divided into three areas: a forum for frank conversation, a sanctum for a meeting of minds, and a space for ecology and the natural world. In the early 1980s, Perna published Evolución de la geografía urbana en Caracas (Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1981), which is considered an essential book in the field. Today, the Foundation that bears his name is housed in what was once his home-studio in the Caracas neighborhood of El Pedregal de la Castellana.

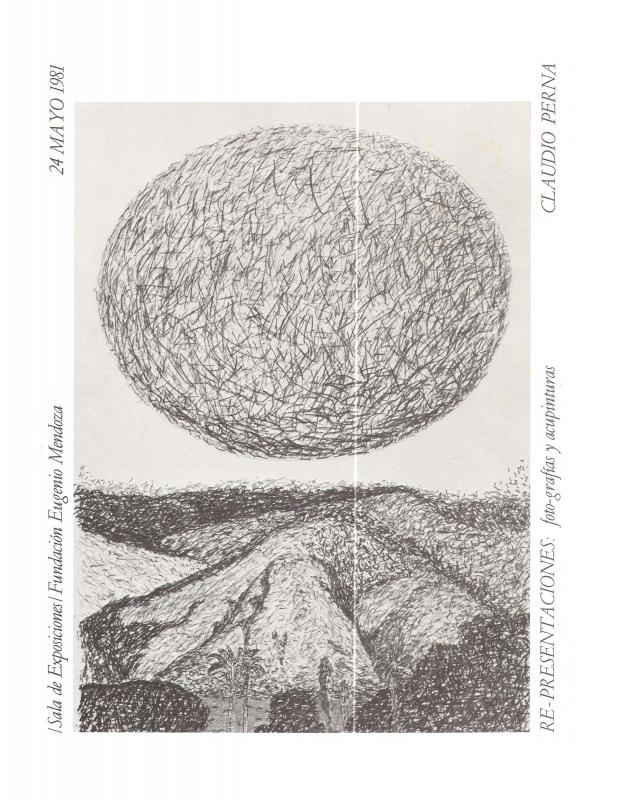

[To read other articles about Perna, see in the ICAA digital archive by Margarita D’Amico “1: Hoy es arte lo que no era” (doc. no. 1068360); by Luis Pérez-Oramas “El autocurrículum de Claudio Perna, escultura social y novela hiperrealista” (doc. no. 1161917); by Roberto Guevara “Claudio Perna o cómo ser libre en la marginalidad” (doc. no. 1080814); by Elsa Flores (untitled) “[Vivir quiere decir dejar huellas…]” (doc. no. 1063156); the following articles by Zuleiva Vivas: “Visión panorámica de las nuevas cartografías” (doc. no. 1157158); “Los nuevos procesos y la representación figurativa” (doc. no. 1157174); “Claudio Perna y el arte del pensamiento” (doc. no. 1163950); “Las opciones del tiempo para el nuevo espíritu” (doc. no. 1065674); and “Intervención creativa en el contexto social” (doc. no. 1161969); by María Elena Ramos “Arte?idea–geografía” (doc. no. 1080766); by Lourdes Blanco “Claudio Perna: fotocopias” (doc. no. 1080715); and by Mara Comerlati “Claudio Perna. Lo fundamental es inventar. Este domingo expondrá más de cincuenta dibujos en la Sala Mendoza” (doc. no. 1068403)].