July 26, 2022

Luz Muñoz, Chief Cataloguer for the ICAA, was among the first in her home country to think about how to systematize access to Chilean contemporary art documents. When local records are few and fragmentary, Muñoz recognized that a “digital copy can preserve and safeguard our heritage.” In this two-part post she reflects on the early history and collaborative process behind the ICAA’s Documents Project. Click here to read Part I.

The process of turning a document into an electronic file in the Documents of Latin American and Latino Art project involves several steps and includes the participation of a chain of people.

The technical infrastructure required to do the job, such as scanners or cameras to make digital copies and laptop computers, was provided to the local teams by the ICAA.

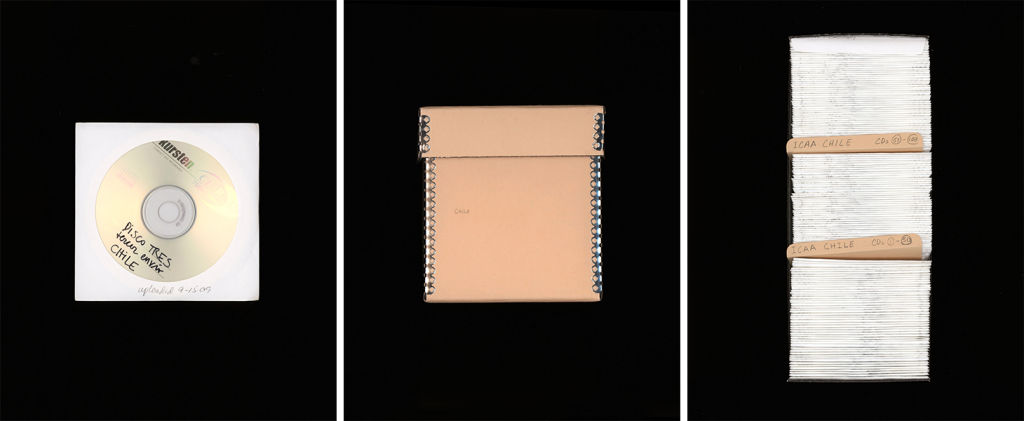

Digital copies were made of the documents that had been selected from local sources; these copies were sent to the ICAA’s imaging department. In the early years, copies were conveyed on CDs, but later a system was set up for online transmission.

The same was done with the files containing bibliographic details: the source from which the information had been taken, whether an article or part of a document, book, or leaflet, which formed the basis of the critical synopses and annotations which, ultimately, have been among the project’s most important contributions.

Digitizing images was a challenge for us, presenting us with a steep learning curve. Collaborative efforts between institutions and the researchers’ private networks made it possible for us to accomplish this process.

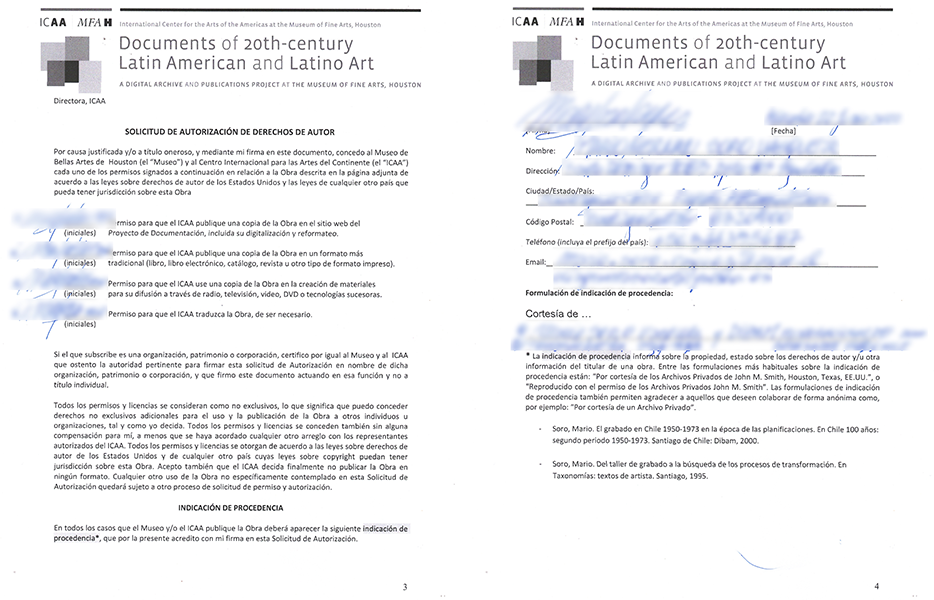

Securing permission to publish was approached in two different ways. Some requests were made directly from Chile, while others were managed by the Houston team through the ICAA copyright department.

Our experience in Chile was not exempt from trial and error, meaning that we were able to refine our methodologies and improve our results as we worked on the project.

In the second phase of the process, all the material that had been collected and processed, including all the content that had been generated by the researchers, was sent to the central ICAA team at the MFAH.

While I was completing my postgraduate studies in Geneva, the ICAA asked me to keep working on the project, this time in association with the central team in Houston. I have worked with them since 2008 and have, for a number of years, been responsible for the Documents Project’s digital archive’s cataloguing.

The central team at the ICAA-MFAH takes care of the next stage; that is, the processing of the data and images in the database that will eventually become part of the digital archive in the website. Being part of a project of this nature has been very rewarding for me; it has been a wonderful experience and has taught me a lot. On that subject I would like to refer to certain aspects of what we do that I believe are important.

With today’s technology we can access digital databases to find documents that can “travel” anywhere in the world, wherever a researcher or student might be looking for them; it is essential, therefore that this be an open access project. I also find it interesting that the project has only taken digital copies of the materials, leaving the originals in their place of origin or in the collections in which they were archived.

Other than providing access and disseminating knowledge to the world, what can a digital document do or offer? A digital copy can preserve and safeguard our heritage in a permanent format in the event that, for whatever reason, an archive is destroyed or damaged at its place of origin, or a document can no longer be accessed (which happens often) for reasons to do with preservation; in such cases the digital copy can provide access to its content. An example of how virtual reality has changed our lives.

In conclusion, the Documents of Latin American and Latino Art project, which is the result of the joint effort made by teams of professionals, has created a website with the most extensive database of its kind in the world. This is largely due to the type of content offered on the site, which opens up a universe to anyone, with no need to travel to the place where a document originated. Getting these documents digitized and making them available to the public has been a great journey.

This project has been built step by step and is, in my opinion, interesting at several levels. In Chile, the first step was to find and reclaim the documents, archives, and primary sources that form the basis of our art history, and to draw attention to local networks and histories, to names that had never been acknowledged by institutional histories up to that point in time. The project has thus helped to open spaces for new research, new historiographies.

At another level it is rewarding to be able to provide anyone in the entire world with access to the documents and other content assembled in the website. This means greater visibility for Chilean and Latin American art and Latino art in the United States. It has cost a great deal to be able to show their histories. We should also note that it is a democratization of access to vital information.

Translated by Tony Beckwith