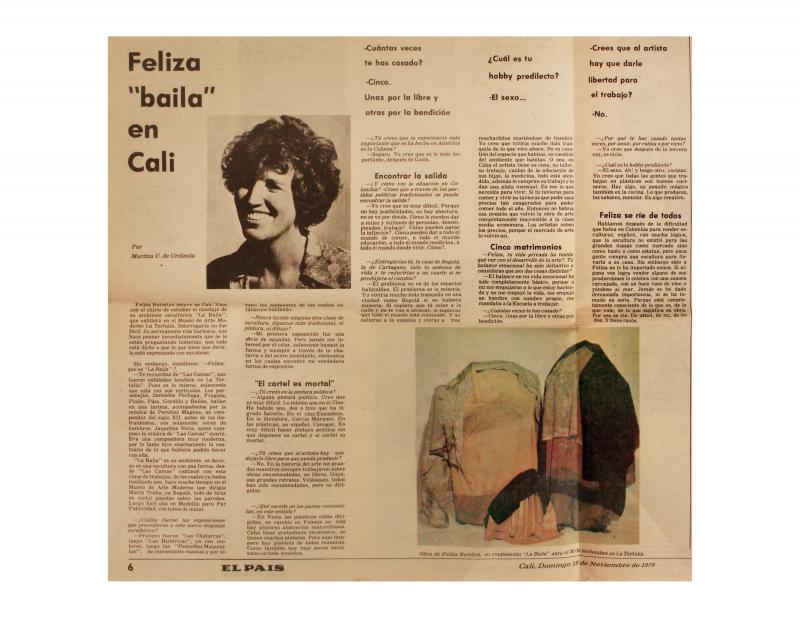

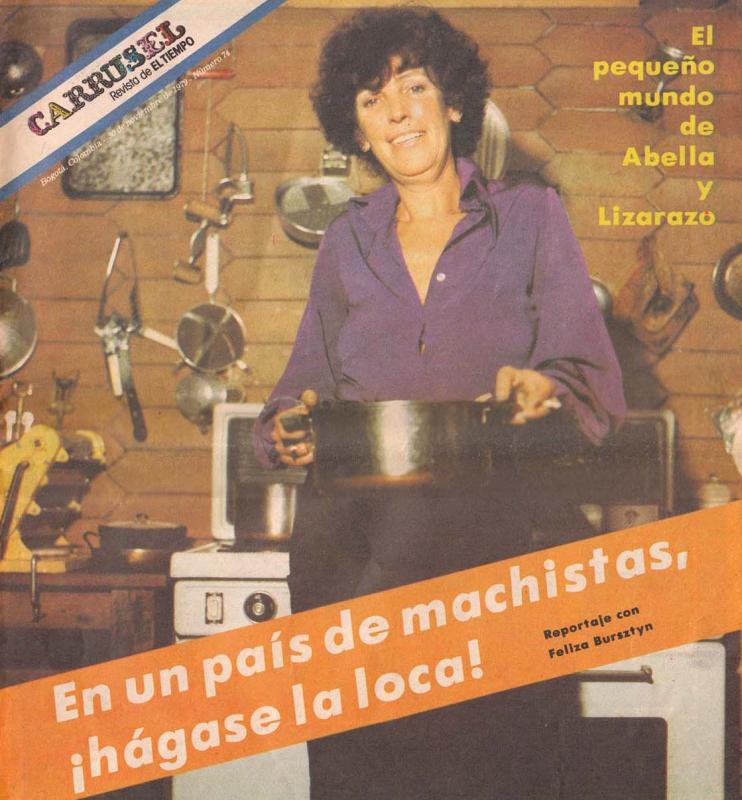

This article should not be seen in the context of a variety and entertainment magazine. The text of the Colombian journalist, Beatriz Zuluaga, is a very interesting invitation into the daily world of Feliza Bursztyn (1933–1982). The story brings into play the sculptor’s friends: Alejandro Obregón (1920–1992) and Juan Gustavo Cobo (born 1948), among other artists, writers, and politicians who were key figures in Colombian culture. These were people who often visited her workshop and were part of an intellectual milieu in which there was an exchange of ideas, criticism, books, white rum, and mutual support. In the midst of those visits, there were discussions of all kinds, including the express complaints of her visitors about tripping over the scrap metal spread around on the floor. The visitors would often ask Bursztyn about which of the strewn pieces would be used for a work, and her blunt reply would be: “eso es una obra” [that is a work]. In the article, the writer shows the sculptor’s direct, day-to-day relationship with the material she used for her works. The immediacy of her work with the scrap metal is evident; there were no themes or rules imposed; she worked with irreverence and had the ability to pose questions using the form of sculpture. Meanwhile, she would respond to questions put to her in interviews with monosyllables, roars of laughter, and paradoxes. Beyond the humor and the laughter described by the interviewer as a constant in the conversation, and taken together with the other interviews included in this project, another important issue emerges from this document. The sculptor’s responses reinforce her distance from becoming a member or militant in any political or women’s group. In this regard, it is worth remembering Bursztyn’s ironic yet precise comments when asked if she was a feminist. (See: “Feliza ‘Baila’ en Cali” [Feliza “Dances” in Cali], doc. No. 858174; and “En un país de machistas, ¡hágase la loca!” [In a Sexist Country, Be the Crazy Lady!], doc. No. 858193.)