In this essay, Mário de Andrade (1893–1945) discusses one of the most important aspects of painting produced in São Paulo during the 1930s and 1940s. He is referring to the fusion of traditional themes with technical and formal knowledge that achieves a given pictorial goal. This was the defining characteristic of the work by artists who were involved with the FAP (Familia Artística Paulista) from 1937, and whose paintings were exhibited for the first time at the Hotel Esplanada in São Paulo. The members of the FAP included: Aldo Bonadei (1906–1974), Alfredo Volpi (1896–1988), Carlos Scliar (1920–2001), Clóvis Graciano (1907–1988), Ernesto De Fiori (1884–1945), Francisco Rebollo (a Spaniard), Fulvio Penacchi (1905–1992), Mario Zanini (1907–1971), Paulo Rossi Osir (1890–1959), Reneé Lefévre (1910–1996), Vittorio Gobbis (1894–1968), and Waldemar da Costa (1904–1982). Most of them were Italian by birth, and some were already members of the group known as Grupo Santa Helena. The group organized three “salões” [Salons] between 1937 and 1939.

On the subject of the beginning of the above-mentioned painting movement in the 1930s, see the essay by Mário de Andrade on “Hugo Adami” [ICAA digital archive, doc. no. 783916]. The São Paulo magazine Revista Acadêmica (1939–1940) devoted an issue to the life and work of the painter Lasar Segall (doc. no. 1110322). See also the essay by Olívio Tavares de Araújo about Volpi “Com os olhos da história” (doc. no. 1111203).

It would be difficult to sum up in just a few words the legacy and the writings of Mário de Andrade, who was a folklore researcher, cultural administrator, art critic, poet, and musicologist. In addition to his creative works, de Andrade was the driving force behind the internal structuring of SPAN (Servicio del Patrimonio Artístico Nacional), and a key figure in the group that was involved in the 1922 Semana de Arte Moderna. He was a prolific writer whose works were widely published in Brazilian periodicals and whose subjects included history, literature, music, folklore, and photography, a field he practiced himself.

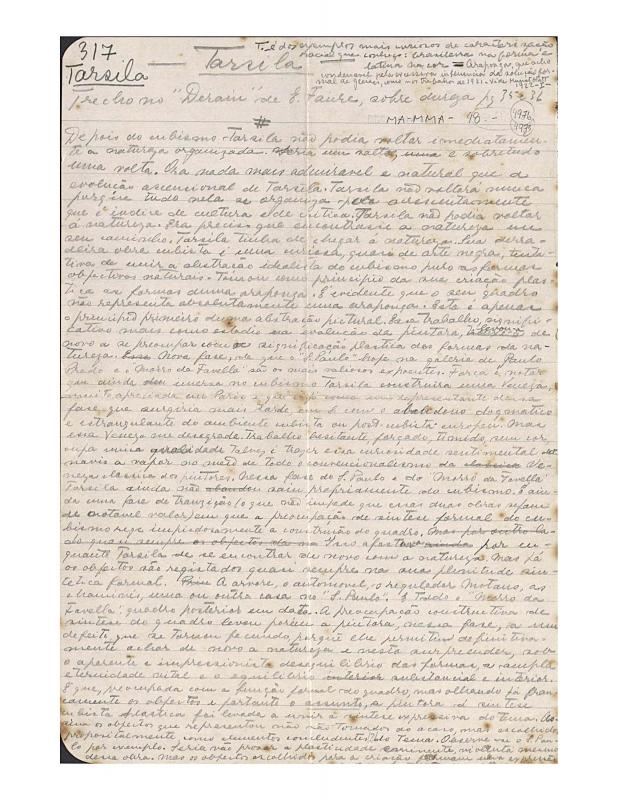

During the same year in which he wrote pioneering essays on the painting of Tarsila do Amaral (doc. nos. 781921 and 781938), he also published a novel-rhapsody that became a classic of Brazilian experimental modernism: Macunaíma: o herói sem nenhum caráter (1928) [Latin American version by Héctor Olea, Macunaíma (Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1977; Barcelona: Octaedro, 2005)].