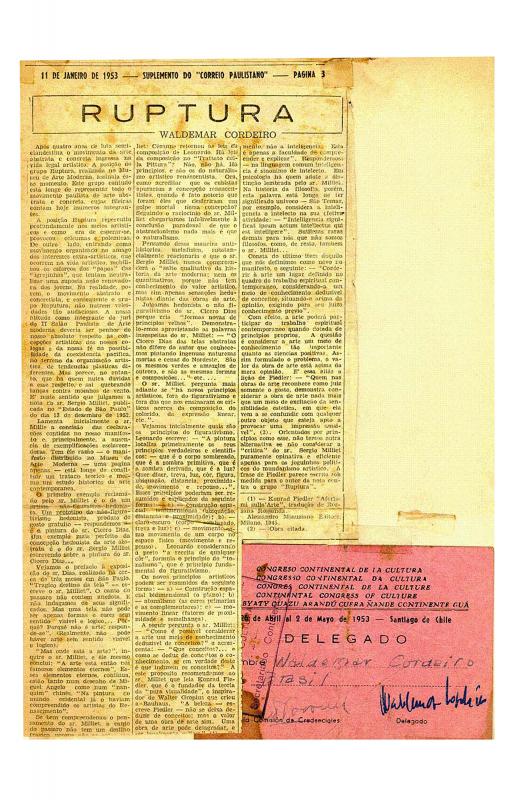

Though the manifesto was signed by all members of the ruptura group, there is no doubt at all that it was written by Waldemar Cordeiro, the group’s theoretician. In fact, the arguments presented and certain phrases in the document are identical to those expressed in some of the articles and essays Cordeiro published in the São Paulo press at the time. The manifiesto ruptura (all lower case letters) [rupture manifesto] was distributed to members of the public during the group’s opening exhibition at the Museu de Arte Moderna in the city of São Paulo on December, 1952. This document was the first published acknowledgement of the debate between figuration and abstraction that simmered in both São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro during the 1940s, a step that helped to drive a wedge between supporters of abstract expressionism and those who favored concrete art. In spite of the dense and condensed nature of the text, the manifesto also hints at how art might be used in practical applications. There was an immediate backlash from conservative critics (led by Sérgio Milliet and published on December 13, 1952, in O Estado de S. Paulo) who felt that their interests were being threatened [see doc. no. 1085337]. On the other hand, one of the defining characteristics of the Brazilian concrete art movement—especially the version that initially evolved in São Paulo—was its identification with the “developmental ideology” that was driving Brazil’s industrial growth during the postwar period. Most of the artists in the ruptura group made their living in the fields of graphic arts, industrial and landscape design, illustration, and advertising. To view the manuscript of the ruptura manifesto, see [doc. no. 1232213].

It should be noted that the São Paulo group was very cosmopolitan since, with the exception of Geraldo de Barros and Luiz Sacilotto (both of whom were born in the state of São Paulo), all the original members were immigrants. The rest of the signatories to the manifesto were from Europe: Lothar Charoux (Austria), Kasmer Féjer (Hungary), Leopold Haar (Poland), Anatol Wladyslaw (Poland), and Cordeiro (who was born in Rome, Italy, though his father was Brazilian). Ever since his arrival in Brazil in the late 1940s, when he was twenty years old, the combative painter, designer, landscape artist, and art critic Waldemar Cordeiro (1925–73) published articles in newspapers and magazines in São Paulo, where he lived, and eventually became the leader of the concrete art movement and the spokesman for the ruptura group.

The group’s decision to use a lower case letter in the movement’s name was not gratuitous, but was based on specific design criteria. One of the members, for example, was Geraldo de Barros, whose poster for the Fourth Centenary of the City of São Paulo (1954) won first prize two years after the group was founded. The goal of the design was to achieve a measure of symmetry in the name; the ‘t’ was to function as an axis or mirror; the upper part of the ‘p’ was intended as a reflection of the ‘a’. To the left and right of the ‘t’ the groups of letters ‘rup’ and ‘ura’ created an unmistakable visual vibration.