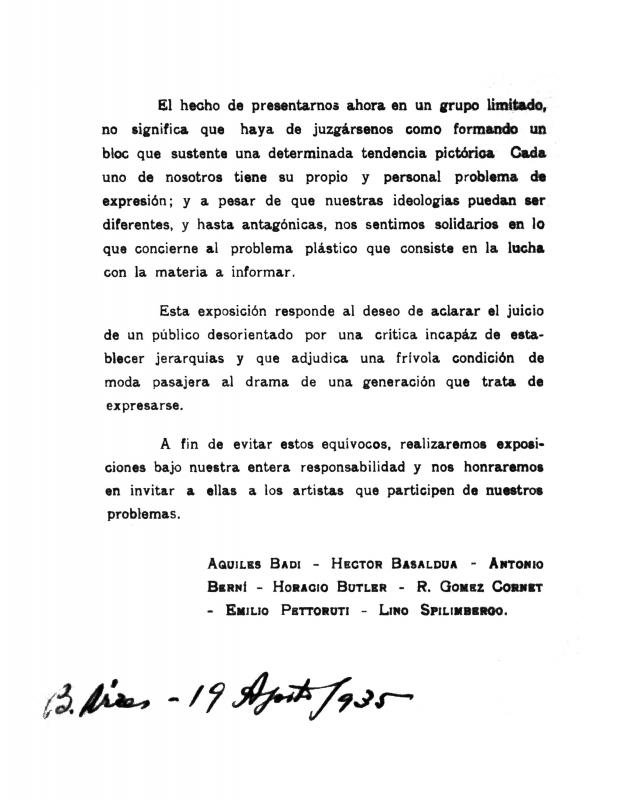

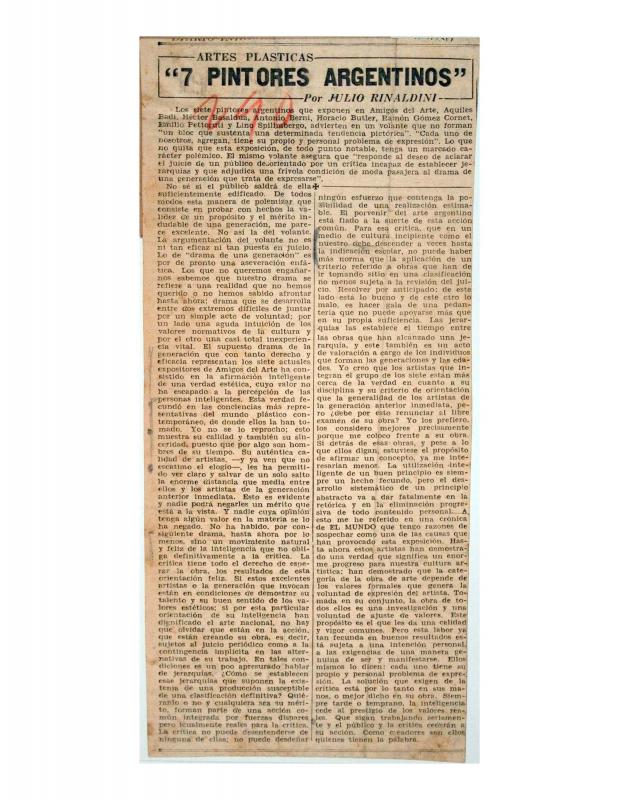

The modernization of art forms in Argentina had one of its main periods in the 1920s. Following the artists linked to the Martín Fierro journal—Emilio Pettoruti (1892–1971), Xul Solar (1887–1963) and Norah Borges (1901–98)—toward the end of the decade Alfredo Guttero’s (1882–1932) activities came to light, in addition to that of the Artistas del Pueblo [Artists of the Town] with social political engraving, and the local activity of the artists who trained in Paris: Aquiles Badi (1894–1976), Horacio Butler (1897–1983), Héctor Basaldúa (1895–1976), Raquel Forner (1902–88), Alfredo Bigati (1898–1964), Antonio Berni (1905–81) and Lino Enea Spilimbergo (1896–1964). In the early 1930s, there was a confrontation between two poles. On the one hand, the artists who defended political art, driven, in 1933, by the arrival of Mexican painter David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974); its key figures were Berni and Spilimbergo. On the other hand, those who proposed the formal renewal of pure art, among them Emilio Pettoruti, Butler, and most of the artists trained at the so-called School of Paris. However, both circles shared an awareness of being modern artists in overt opposition with academic Naturalism. The emergence of Nationalism during the 1930s changed the confrontational policies of Communism with the liberal, socialist, and democratic sectors in order to form antifascist and antimilitaristic alliances. This document presents the growing activity of the “modern artists” at the beginning of 1935, just before the alliance with the “political” artists by means of an exhibition and manifesto in defense of modernity. The Argentinean Right shaped its artistic discourse in a position against Siqueiros through its journals Bandera Argentina [Argentinean Flag] and Crisol [Melting pot], which represented the Catholic Nationalism that had gained momentum ever since the 1930 military coup. Bandera Argentina can be considered as a combat organism against communism, an ideology that is destructive and foreign to Argentinean culture, according to its guidelines. The nationalist sectors of the 1930s had defined Argentinean culture as an identity with a Hispanic, Catholic, and integral background. The alliance of a group of artists, recognized as modern artists, with the followers of Siqueiros is attacked in this document. The significance of this text is that Nazi arguments about Entarte Kunst [“Degenerate Art”] are used, and clearly establish the spreading of these ideas in the 1930s Argentina. The article therefore criticizes the exhibition 7 pintores argentinos : exposición retrospectiva [Seven Argentinean Painters: A Retrospective Exhibition], presented at Amigos del Arte, in August of 1935, in which Aquiles Badi (1894-1976), Horacio Butler (1897–1983), Héctor Basaldúa (1895–1976), Antonio Berni (1905–81), Ramón Gómez Cornet (1898–1964) , Emilio Pettoruti (1892–1971) and Lino Enea Spilimbergo (1896–1964) participated.For the manifesto of the modern artists, see document no. 733845, and for the exhibition catalog 7 pintores argentinos : exposición retrospectiva [Seven Argentinean Painters: A Retrospective Exhibition], see document no. 733857. For the critique of the manifesto from anti-fascist positions, see document no. 733926 (Julio Rinaldini, Artes plásticas: 7 pintores argentinos [The Visual Arts: Seven Argentinean Painters]).