The modernization of art forms in Argentina had one of its main periods in the 1920s. Following the artists linked to the Martín Fierro journal—Emilio Pettoruti (1892–1971), Xul Solar (1887–1963) and Norah Borges (1901–98)—towards the end of the decade Alfredo Guttero’s (1882–1932) activities came to light,in addition to that of the Artistas del Pueblo [Artists of the Town] involved with social political engraving, and the local activity of the artists who trained in Paris: Aquiles Badi (1894–1976), Horacio Butler (1897–1983), Héctor Basaldúa (1895–1976), Raquel Forner (1902–88), Alfredo Bigati (1898–1964), Antonio Berni (1905–81) and Lino Enea Spilimbergo (1896–1964).

In the early 1930s, there was a confrontation between two poles. On the one hand, the artists who defended political art, driven in 1933 by the arrival of Mexican painter David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974); its key figures were Berni and Spilimbergo. On the other hand those who proposed the formal renewal of pure art; among them Emilio Pettoruti, Butler, and most of the artists trained at the so-called School of Paris. However, both circles shared the awareness of being modern artists in overt opposition with academic Naturalism.

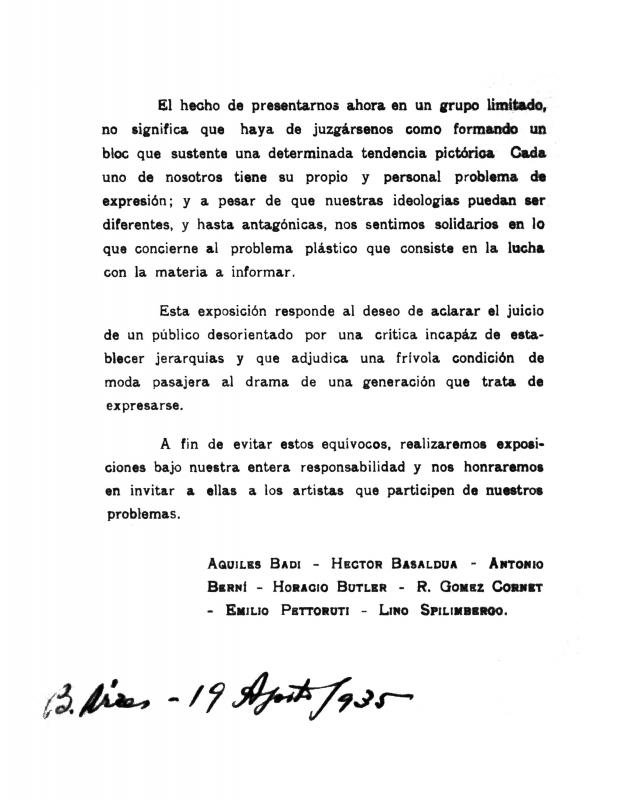

The emergence of Nationalism during the 1930s changed the confrontational policies of Communism with the liberal, socialist, and democratic sectors in order to form antifascist and antimilitaristic alliances. This document presents the cultural response to this policy in a retrospective show of “modern artists” to point out the joint task carried out by these artists. Having been strongly opposed only two years before, they strove in tandem to impose artistic modernity since the 1920s. Therefore, a manifesto justified the joint presentation defending modernity, and beyond their differences regarding both aesthetic and political issues.

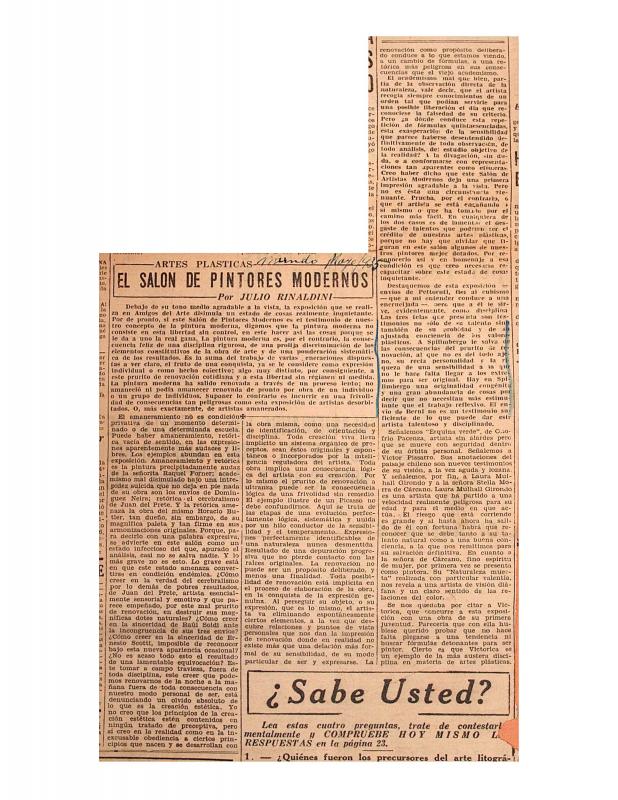

Julio Rinaldini (1890–1968), was a distinguished art critic and essayist of the first half of the 20th century, who wrote for the main journalistic media of Argentina, such as La Nación [The Nation] and El Mundo [The World]. He participated in the debates about modern art and, in a broader context, he defended culture from totalitarianism. In this sense he was a collaborator in Argentina Libre [Free Argentina], Cabalgata [Cavalcade] and Saber Vivir [Knowing How to Live].

For the manifesto of the modern artists in 1935, see document no. 733845; for the exhibition catalog, see document no. 733857. Also, for the critique of the modern artists by Julio Rinaldini in El Mundo [The World], published in May of 1935, see document no. 767941.