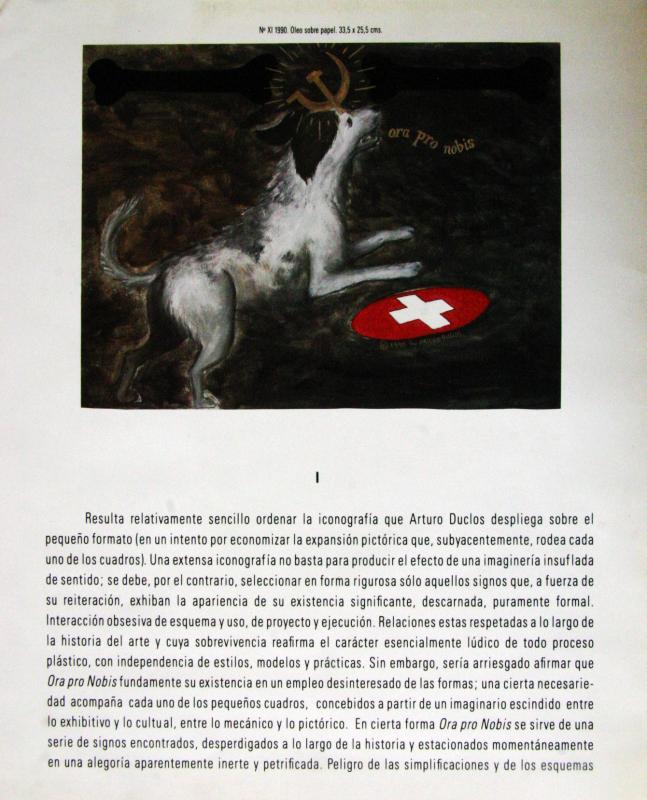

“El ojo y la mano” was written by the theorist and art critic Guillermo Machuca (1962–2020) on the occasion of his curatorial project for El ojo de la mano, the exhibition of works by Arturo Duclos (b. 1959) at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. His retrospective curatorship brought together works produced from 1983 to 1995, when the exhibition took place. Machuca had previously written “Ora pro nobis” (doc. no. 749208), in which he describes Duclos’s eponymous 1991 exhibition, looking back at some of the artist’s earlier works such as La lección de anatomía (1985) and even his exhibition La isla de los muertos (1989).

Shortly after leaving the Escuela de Artes, Arturo Duclos became involved in the Chilean art scene at a time when experimentation and conceptualism were gaining ground. The cultural theorist Nelly Richard (b. 1948) had identified a group of neo-avant-garde artists, which she referred to as the Escena de Avanzada. As from the 1980s “the repositioning of painting” became a major subject for discussion, focusing on the traditional practice that had been challenged in Chile in works by Eugenio Dittborn (b. 1943), Carlos Altamirano (b. 1954), and Juan Domingo Dávila (b. 1946), among others. This "return to painting" tended to favor the artist’s expressiveness and inner world, while ignoring the complicated political reality the country was experiencing under the dictatorship. Duclos—who was a member of the generation of artists who chose painting—took part in exhibitions that demonstrated the prevailing tensions of the times, including BENMAYOR/DÍAZ/DITTBORN/DUCLOS/LEPPE (1983) and Fuera de serie (Outstanding, 1985), among others. Machuca claimed that, for certain artists, the 1985 exhibition heralded the end of the Escena de Avanzada. That same year, Duclos showed La lección de anatomía at the Bucci gallery, where he combined paintings with installation. As Machuca mentions, that exhibition marked an inflection point when the artist moved away from installation and focused (initially) on a more expressive kind of painting, followed by an ironic approach. In “Retroactivaciones de un proceso” (doc. no. 730159), Richard discusses this particular exhibition; and in “Return to the pleasurable” (doc. no. 743686)—a chapter of her book Margins and Institutions. Art in Chile Since 1973—she notes the prevalence of “the gesture” in the new style of painting that was used as an act of liberation that she associated with an irrational passion that sought to express the painter’s inner world, suggesting that Duclos’s paintings were an exception.

La lección de anatomía (1985) is the title of one of the artist’s works and one of the defining exhibitions of his career, an installation that consists of more than one hundred human bones, including three skulls. These skeletal remains represent an archeological culture and the dictatorship in Chile (1973–90) that was responsible for all manner of human rights violations, which meant death and disappearances. From a formal perspective, the work combined a reflection on painting in the installation, since the act of painting the bones is akin to recovering them with a new skin, where the painter sought to allude to the traditional concept of flesh that seeks to give credibility to the bodies represented. [For information about other exhibitions and discussions in which Duclos participated, see the following in the ICAA Digital Archive: “Pequeña novela del grabado chileno” (doc. no. 736031) by Justo Pastor Mellado; “Intertexto” (doc. no. 734686) by Nelly Richard, and “Todo fuera de contexto: todo fuera de ontext es el efecto de una cita” (doc. no 734699) by Pablo Oyarzún.]