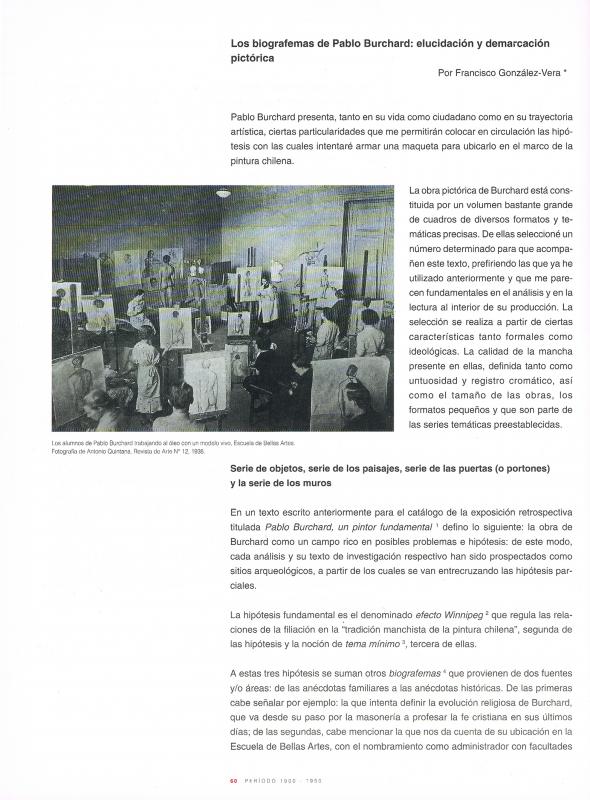

In 1965, the painter José Balmes (1927–2016) published his “Confesión artística” (Artistic Confession) in the Anales de la Universidad de Chile. He had been associated with the university ever since he enrolled as a student in 1944 and studied under the painters Camilo Mori (1896–1973) and Pablo Burchard (1875–1964). A year after completing his training as a painter, he started work as a professor at the Escuela de Bellas Artes, in addition to being director of the Visual Arts department and dean of the arts faculty, a position he held for just a year due to the coup d’état of 1973. As a result of that watershed event, and because of his membership in the Chilean Communist Party and his support of the Unidad Popular government of President Salvador Allende (1908–1973), Balmes went into exile for a second time. [On the subject of his time as a professor, see the following in the ICAA Digital Archive: “El maestro de los jóvenes” (doc. no. 751500) by Patricio de la O; for more information about the painters who trained Balmes, see: “Confesión artística” (doc. no. 748526) by Mori and “Los biografemas de Pablo Burchard: elucidación y demarcación pictórica” (doc. no. 773704) by Francisco González Vera.]

In 1952, Balmes married Gracia Barrios (1927–2020), the daughter of the novelist of the Generación del ’13, Eduardo Barrios; this is an important detail because they conducted a great deal of their formal research together, although they each worked in their own visual language. They traveled in Europe from 1954 to 1956 and, on their return to Chile, were critical of what they saw being produced in local art circles, which they considered to be behind the times compared to what they had seen and learned on their travels. Joining forces with the artists Eduardo Martínez Bonati (b. 1930) and Alberto Pérez (1926–1999), they started the Grupo Signo, a group that was highly critical of traditional painting (not just the local version) and was driven by the political turmoil of the 1960s. [On the subject of Signo, see “Presencia del Signo” (doc. 751514) by Pérez, one of the members of the group.]

“Confesión artística” includes early thoughts on painting that were then discussed in depth. In formal terms, Balmes’s paintings were increasingly filled with gestures and daubs or marks. In his essay, he refers to Santo Domingo (1964¬–65), his series about the North American armed intervention in the Dominican Republic. He created other series of large-scale paintings in the same “testimonial” style, as he called it: Vietnam (1966–68), Che Guevara (1968–69), and No al Fascismo (1971–73). While living in exile in Paris, his paintings continued to express his political resistance; it was during that period that he produced Represión (1974–76) and the paintings Lonquén (1979) and Homenaje de André Jarlan (1987), among others. [On the subject of his work, see also: “Balmes: dos tierras” (doc. no. 735080) by Gaspar Galaz; regarding the evolution of Chilean art see: “La novela chilena del grabado” (doc. no. 736035) by Justo Pastor Mellado.]