This monographic text by the essayist Adriana Valdés (b. 1943) appeared in a document that was devoted exclusively to the work of Roser Bru (1923–2021). Valdés reviews a significant number of paintings, dividing them into periods to help the reader gain a better understanding of this painter’s work.

The artist Roser Bru was from Catalonia. Like José Balmes, she arrived in Chile with her family aboard the Winnipeg, the ship that President Pedro Aguirre Cerda chartered at the end of the Spanish Civil War (1939). She immediately enrolled at the Escuela de Bellas Artes (Santiago). In 1957 she joined the Taller 99, the print workshop founded by Nemesio Antúnez (1918–1993); in fact, in “De cómo empezó la enseñanza de Antúnez”—ICAA Digital Archive (doc. no. 774610)—Bru discusses her printmaking experience, which she practiced in addition to her painting and drawing. Bru had been active in the Chilean arts scene since 1957. After a career that spanned sixty years, she was awarded the Premio Nacional de Artes Plásticas (2015), the Chilean government’s highest honor for artists. [For more information about the Taller 99, see: “Prólogo para catálogo de Tercera Bienal del Grabado” (doc. no. 745065) by Antúnez.]

She painted many portraits, and most of her subjects were people in the cultural field, such as Franz Kafka, Milena Jesenská, Ana Frank, Francisco de Goya, Frida Kahlo, Virginia Wolf, Arthur Rimbaud, Miguel Hernández, Enrique Lihn, Gabriela Mistral, and Julieta Kirkwood, among others. Her works often rely on memory, quotes from art history (Velásquez in particular), and, in one case, bread and watermelon, which she identifies with women and fertility.

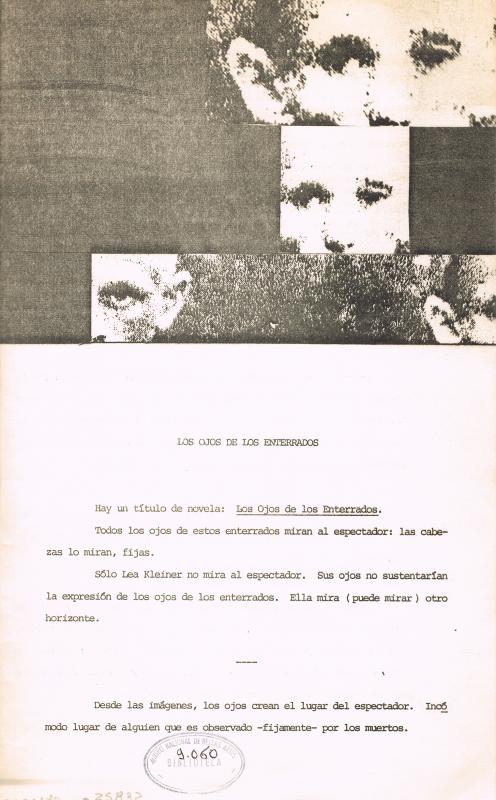

Valdés and Bru had an artistic-theoretical relationship that led to collaborative efforts begun in the late 1970s, which is when Valdés wrote “Los ojos de los enterrados” [Buried People’s Eyes] (doc. no. 740321) on the occasion of Bru’s exhibition Kafka y nosotros at the Galería Cromo (1977). They kept up their relationship until the artist’s most recent exhibitions. One of the aspects Valdés notes in Bru’s work is her relentless focus on the sociopolitical situation during the Pinochet military dictatorship (1973–90), a continuation of the fight against fascism she had brought with her to Chile as a young woman. Many of her works explicitly refer to the plight of people who have been arrested or, later on, disappeared. Her work Cal, cal viva (1978), which is part of the collection at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, refers to the “Hornos de Lonquén,” where the remains of fifteen peasants, who had been arrested in 1973, were found. Bru used her printmaking skills to work with the feminist and women’s movements, both of which were against the dictatorship.