This ten-question interview of Beatriz González by art critic Marta Traba was published in the exhibition catalogue of González and Luis Caballero’s artworks held at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá in 1973. Both artists had been Marta Traba’s students at the Universidad de los Andes [University of the Andes]. González’s answers are wry and, at times, evasive, especially when she is asked to comment about the sarcasm in her work. For her, irony is something quite natural, which stems from living in a nation that takes its history (in a non-critical approach) too seriously. She stresses that there is no consideration for artists in Colombia, a condition that allows for freedom of experimentation. Traba, therefore, asks González to directly describe her works that go beyond traditional techniques and materials, that is, her series of furniture pieces, in which the artist reproduced nineteenth-century paintings and religious icons on everyday industrial, metallic furniture. An analysis in this regard is provided in the essay “Las imágenes de los otros: Una aproximación a la obra de Beatriz González em las décadas del sesenta, setenta y mitad del ochenta” [Other People’s Images: A Look at Beatriz González’s Work from the 1960s, 1970s, and Early 1980s] by Carmen María Jaramillo [see ICAA Digital Archive (doc. no. 1343092)].

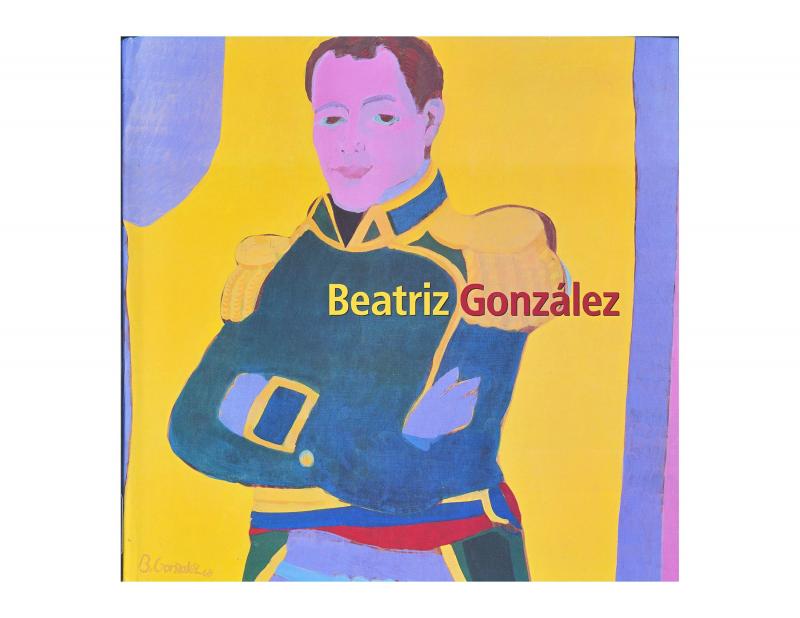

Beatriz González (b. 1938) is a Colombian artist based in Bogotá. Her career spans six decades, from the early 1960s to today, and includes paintings, drawings, silkscreen prints, and curtains, as well as three-dimensional paintings on recycled furniture or everyday objects. González, who calls herself a “provincial artist,” appropriates and reinterprets images from the mass media and notable notorious European classic artworks; therefore, she has often been associated with the Pop Art movement, a position that she ostensibly rejects. Her work, in fact, does not deal with consumer culture itself; instead, it makes a chronicle of Colombia’s recent history. Indeed, it implies an investigation of middle-class taste in Latin America with regard to European artworks and exposes the uneven relationship between her country and the mainstream of the hegemonic centers (Europe and the United States), which is an undeniable legacy of colonialism. Beyond her expansive oeuvre, González has worked as a curator and museum education, in addition to art writing. [To read some examples of her critical writing on her own work, see documents numbers (1078663) and (1093273); in reference to other artists see documents (860646), and (1098901)].

Marta Traba (1930–1983) was a native Argentinian and Colombia-based art critic who studied in Europe and began her career writing for Ver y estimar, the art magazine founded by the director of the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella, Jorge Romero Brest. In the 1950s and 1960s, Traba lived in Colombia, her adoptive country, where she became a prominent figure in the cultural world, writing art criticism in national newspapers and magazines, participating in television programs, as well as teaching at several universities. Initially, Traba gave primacy to aesthetics, privileging an autonomous art devoid of overtly political content and characterized by universal elements and themes. Her sharp, uncompromising, and provocative positions often ignited debates with the opposition—the nationalist, conservative critics— and the supporters of internationalism. In 1968, because of her open opposition to the government of president Carlos Lleras Restrepo, she was forced into exile. She lived in Montevideo (Uruguay), Caracas (Venezuela) San Juan (Puerto Rico), Washington, DC, and finally Paris, teaching at local universities and writing art criticism. If at the beginning of her career she supported high modernism, she later became distrustful of experimental art—such as Pop Art, happenings, and Conceptual art—which she considered as uncritical imports from hegemonic countries (to wit, the United States). She was among the first art critics to think of Latin American art as a whole, as non-derivative in some cases, and to suggest the idea of a shared artistic language among the Latin American countries that should overcome cultural dependency as well as resist homogenizing art approaches from central nations.